I confess that I cannot make head or tail out of Heraclitus. The best that I can come up with is that his pronouncements -- "you cannot step into the same river twice," "the way up is the way down," etc. (these are paraphrases of the numerous translations out there) -- remind me of Lao Tzu's Tao Te Ching. However, whatever the fragments mean, they certainly sound good.

Two of my favorite poets have written poems inspired by those fragments, and the poems provide me with a better clue as to what Heraclitus is up to than my own bumbling attempts to figure him out. First, Derek Mahon:

Heraclitus on Rivers

Nobody steps into the same river twice.

The same river is never the same

Because that is the nature of water.

Similarly your changing metabolism

Means that you are no longer you.

The cells die, and the precise

Configuration of the heavenly bodies

When she told you she loved you

Will not come again in this lifetime.

You will tell me that you have executed

A monument more lasting than bronze;

But even bronze is perishable.

Your best poem, you know the one I mean,

The very language in which the poem

Was written, and the idea of language,

All these things will pass away in time.

Derek Mahon, Collected Poems (The Gallery Press 1999).

In my next post, we will see what Louis MacNeice has to say about the ever-flowing world of Heraclitus.

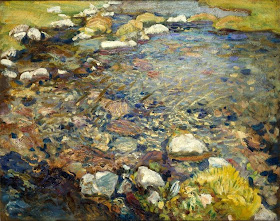

John Singer Sargent, "Stream in the Val d'Aosta" (c. 1909)

Wednesday, June 30, 2010

Monday, June 28, 2010

The Summer Of 1914: John Nash, Philip Larkin, And Edward Thomas

My previous post included this painting by John Nash (1893-1977):

It is titled "A Gloucestershire Landscape." Nash painted it in the summer of 1914. The date put me in mind of Philip Larkin's poem "MCMXIV." These are the concluding stanzas:

And the countryside not caring:

The place-names all hazed over

With flowering grasses, and fields

Shadowing Domesday lines

Under wheat's restless silence;

The differently-dressed servants

With tiny rooms in huge houses,

The dust behind limousines;

Never such innocence,

Never before or since,

As changed itself to past

Without a word -- the men

Leaving the gardens tidy,

The thousands of marriages

Lasting a little while longer:

Never such innocence again.

On June 24 of 1914, Edward Thomas made the following entry in one of his notebooks:

And the countryside not caring:

The place-names all hazed over

With flowering grasses, and fields

Shadowing Domesday lines

Under wheat's restless silence;

The differently-dressed servants

With tiny rooms in huge houses,

The dust behind limousines;

Never such innocence,

Never before or since,

As changed itself to past

Without a word -- the men

Leaving the gardens tidy,

The thousands of marriages

Lasting a little while longer:

Never such innocence again.

("The thousands of marriages/Lasting a little while longer": these are two of the most beautiful and moving lines in Larkin's poetry, I think. And how about "wheat's restless silence"? Larkin is not usually thought of as a "nature poet," but it is hard to beat that.)

Recruits at Exeter, 1914

On June 24 of 1914, Edward Thomas made the following entry in one of his notebooks:

"Then we stopped at Adlestrop, through the willows could be heard a chain of blackbirds songs at 12.45 and one thrush and no man seen, only a hiss of engine letting off steam.

Stopping outside Campden by banks of long grass willowherb and meadowsweet, extraordinary silence between the two periods of travel -- looking out on grey dry stones between metals and the shining metals and over it all the elms willows and long grass -- one man clears his throat -- a greater than rustic silence. No house in view. Stop only for a minute till signal is up."

This entry, of course, marks the genesis of "Adlestrop," the final stanza of which brings us back to Nash's Gloucestershire:

And for that minute a blackbird sang

Close by, and round him, mistier,

Farther and farther, all the birds

Of Oxfordshire and Gloucestershire.

Saturday, June 26, 2010

No Escape, Part Six: "The Bright Field" And "The Water's Quiet Insistence"

In this visit to the land of "wherever you go, there you are," R. S. Thomas offers a possible solution to the problem of not being able to escape from yourself when you attempt to travel to that ever-illusory ideal place. It turns out that the place you long for may be right there in front of you (if you first turn aside a bit).

The Bright Field

I have seen the sun break through

to illuminate a small field

for a while, and gone my way

and forgotten it. But that was the pearl

of great price, the one field that had

the treasure in it. I realize now

that I must give all that I have

to possess it. Life is not hurrying

on to a receding future, nor hankering after

an imagined past. It is the turning

aside like Moses to the miracle

of the lit bush, to a brightness

that seemed as transitory as your youth

once, but is the eternity that awaits you.

John Nash, "A Gloucestershire Landscape" (1914)

Llananno

I often call there.

There are no poems in it

for me. But as a gesture

of independence of the speeding

traffic I am a part

of, I stop the car,

turn down the narrow path

to the river, and enter

the church with its clear reflection

beside it.

There are few services

now; the screen has nothing

to hide. Face to face

with no intermediary

between me and God, and only the water's

quiet insistence on a time

older than man, I keep my eyes

open and am not dazzled,

so delicately does the light enter

my soul from the serene presence

that waits for me till I come next.

John Nash, "Landscape Near Hadleigh" (c. 1945)

The Bright Field

I have seen the sun break through

to illuminate a small field

for a while, and gone my way

and forgotten it. But that was the pearl

of great price, the one field that had

the treasure in it. I realize now

that I must give all that I have

to possess it. Life is not hurrying

on to a receding future, nor hankering after

an imagined past. It is the turning

aside like Moses to the miracle

of the lit bush, to a brightness

that seemed as transitory as your youth

once, but is the eternity that awaits you.

Llananno

I often call there.

There are no poems in it

for me. But as a gesture

of independence of the speeding

traffic I am a part

of, I stop the car,

turn down the narrow path

to the river, and enter

the church with its clear reflection

beside it.

There are few services

now; the screen has nothing

to hide. Face to face

with no intermediary

between me and God, and only the water's

quiet insistence on a time

older than man, I keep my eyes

open and am not dazzled,

so delicately does the light enter

my soul from the serene presence

that waits for me till I come next.

Thursday, June 24, 2010

Siegfried Sassoon: "Blunden's Beech"

Siegfried Sassoon and Edmund Blunden met just after the end of the First World War. Their friendship lasted nearly 50 years -- until Sassoon's death in 1967. In a previous post ("Edmund Blunden and Thomas Hardy": April 22, 2010), we saw Sassoon express his affection for Blunden in the context of comparing him with Thomas Hardy.

Their underlying bond was, as one might expect, their shared experience of the War. And an important element of that bond was their love of the men that they served with. But they also shared a love of poetry, the English countryside, and -- importantly -- cricket.

Blunden (left) and Sassoon (center):

listening to a cricket match.

The following poem appears in Sassoon's collection Rhymed Ruminations (1940):

Blunden's Beech

I named it Blunden's Beech; and no one knew

That this -- of local beeches -- was the best.

Remembering lines by Clare, I'd sometimes rest

Contentful on the cushioned moss that grew

Between its roots. Finches, a flitting crew,

Chirped their concerns. Wiltshire, from east to west

Contained my tree. And Edmund never guessed

How he was there with me till dusk and dew.

Thus, fancy-free from ownership and claim,

The mind can make its legends live and sing

And grow to be the genius of some place.

And thus, where sylvan shadows held a name,

The thought of Poetry will dwell, and bring

To summer's idyll an unheeded grace.

W. H. Burgess, "An Old Beech Tree" (1827)

Their underlying bond was, as one might expect, their shared experience of the War. And an important element of that bond was their love of the men that they served with. But they also shared a love of poetry, the English countryside, and -- importantly -- cricket.

Blunden (left) and Sassoon (center):

listening to a cricket match.

The following poem appears in Sassoon's collection Rhymed Ruminations (1940):

Blunden's Beech

I named it Blunden's Beech; and no one knew

That this -- of local beeches -- was the best.

Remembering lines by Clare, I'd sometimes rest

Contentful on the cushioned moss that grew

Between its roots. Finches, a flitting crew,

Chirped their concerns. Wiltshire, from east to west

Contained my tree. And Edmund never guessed

How he was there with me till dusk and dew.

Thus, fancy-free from ownership and claim,

The mind can make its legends live and sing

And grow to be the genius of some place.

And thus, where sylvan shadows held a name,

The thought of Poetry will dwell, and bring

To summer's idyll an unheeded grace.

W. H. Burgess, "An Old Beech Tree" (1827)

Tuesday, June 22, 2010

John Drinkwater: "Politics"

The following poem is by John Drinkwater (1882-1937).

Politics

You say a thousand things,

Persuasively,

And with strange passion hotly I agree,

And praise your zest,

And then

A blackbird sings

On April lilac, or fieldfaring men,

Ghostlike, with loaded wain,

Come down the twilit lane

To rest,

And what is all your argument to me?

Oh yes -- I know, I know,

It must be so --

You must devise

Your myriad policies,

For we are little wise,

And must be led and marshalled, lest we keep

Too fast a sleep

Far from the central world's realities.

Yes, we must heed --

For surely you reveal

Life's very heart; surely with flaming zeal

You search our folly and our secret need;

And surely it is wrong

To count my blackbird's song,

My cones of lilac, and my wagon team,

More than a world of dream.

But still

A voice calls from the hill --

I must away --

I cannot hear your argument to-day.

Tides (1917).

I recommend a little book by Drinkwater titled The World and the Artist (1922). In it, Drinkwater laments the harmful impact of modern technology on the way we live our lives, and suggests how poetry might rescue us. Alas, this was a lost (though honorable) cause even in 1922.

Samuel Palmer, "The Bright Cloud" (c. 1833)

Politics

You say a thousand things,

Persuasively,

And with strange passion hotly I agree,

And praise your zest,

And then

A blackbird sings

On April lilac, or fieldfaring men,

Ghostlike, with loaded wain,

Come down the twilit lane

To rest,

And what is all your argument to me?

Oh yes -- I know, I know,

It must be so --

You must devise

Your myriad policies,

For we are little wise,

And must be led and marshalled, lest we keep

Too fast a sleep

Far from the central world's realities.

Yes, we must heed --

For surely you reveal

Life's very heart; surely with flaming zeal

You search our folly and our secret need;

And surely it is wrong

To count my blackbird's song,

My cones of lilac, and my wagon team,

More than a world of dream.

But still

A voice calls from the hill --

I must away --

I cannot hear your argument to-day.

Tides (1917).

I recommend a little book by Drinkwater titled The World and the Artist (1922). In it, Drinkwater laments the harmful impact of modern technology on the way we live our lives, and suggests how poetry might rescue us. Alas, this was a lost (though honorable) cause even in 1922.

Samuel Palmer, "The Bright Cloud" (c. 1833)

Sunday, June 20, 2010

"Neurasthenia"

Pleasant discoveries await you if you wander the byways of Victorian poetry. Yes, you will come upon poems that seem to fit what may be called the "Victorian" stereotype. But you may be surprised at what else you encounter. The following poem is by A. Mary F. Robinson (1857-1944).

Neurasthenia

I watch the happier people of the house

Come in and out, and talk, and go their ways;

I sit and gaze at them; I cannot rouse

My heavy mind to share their busy days.

I watch them glide, like skaters on a stream,

Across the brilliant surface of the world.

But I am underneath: they do not dream

How deep below the eddying flood is whirl'd.

They cannot come to me, nor I to them;

But, if a mightier arm could reach and save,

Should I forget the tide I had to stem?

Should I, like these, ignore the abysmal wave?

Yes! in the radiant air how could I know

How black it is, how fast it is, below?

William Holman Hunt, "Our English Coasts" (1852)

Neurasthenia

I watch the happier people of the house

Come in and out, and talk, and go their ways;

I sit and gaze at them; I cannot rouse

My heavy mind to share their busy days.

I watch them glide, like skaters on a stream,

Across the brilliant surface of the world.

But I am underneath: they do not dream

How deep below the eddying flood is whirl'd.

They cannot come to me, nor I to them;

But, if a mightier arm could reach and save,

Should I forget the tide I had to stem?

Should I, like these, ignore the abysmal wave?

Yes! in the radiant air how could I know

How black it is, how fast it is, below?

William Holman Hunt, "Our English Coasts" (1852)

Friday, June 18, 2010

They No Longer Write History Like This

I enjoy the ambition and literary flair of the great British historians of the 19th and early-20th centuries. I am speaking of the authors of those comprehensive multi-volume works that no one undertakes these days. To name but a few: Symonds on the Italian Renaissance, Grote on Greece, Hallam on the Middle Ages, Macaulay on England, Trevelyan on England, Green on England, Froude on England, Carlyle on the French Revolution, Fortescue on the British army. Their knowledge of their subject matter was complete and their scope was all-encompassing. Today, we have specialists.

But what makes these historians wonderful is their writing itself. They thought of themselves as being engaged in a literary undertaking. Of course, they covered (oh, how they covered) the facts. However, they were not merely annalists. They had a story to tell and they told it with style and verve. Here, for instance, is Charles Oman (1860-1946) writing of the Spanish royal family in A History of the Peninsular War (seven volumes):

It is perhaps necessary to gain some detailed idea of the unpleasant family party at Madrid. King Charles IV was now a man of sixty years of age: he was so entirely simple and helpless that it is hardly an exaggeration to say that his weakness bordered on imbecility. His elder brother, Don Philip, was so clearly wanting in intellect that he had to be placed in confinement and excluded from the throne. It might occur to us that it would have been well for Spain if Charles had followed him to the asylum, if we had not to remember that the crown would then have fallen to Ferdinand of Naples, who if more intelligent was also more morally worthless than his brother.

. . .

[Charles] may be described as a good-natured and benevolent imbecile: he was not cruel or malicious or licentious, or given to extravagant fancies. . . . He was very ugly, not with the fierce clever ugliness of his father Charles III, but in an imbecile fashion, with a frightfully receding forehead, a big nose, and a retreating jaw generally set in a harmless grin. . . . He had just enough brains to be proud of his position as king, and to resent anything that he regarded as an attack on his dignity -- such as the mention of old constitutional rights and privileges, or any allusion to the Cortes.

A History of the Peninsular War, Volume I (1902), pages 13-14.

Some may think that this type of historical writing is too "subjective" or too "romantic." I respectfully disagree. To my mind, the writing of history in this fashion follows directly in the tradition of Herodotus, who is well-known for his colorful (and often digressive -- though wonderfully so) style.

Goya, "Charles IV" (1789)

But what makes these historians wonderful is their writing itself. They thought of themselves as being engaged in a literary undertaking. Of course, they covered (oh, how they covered) the facts. However, they were not merely annalists. They had a story to tell and they told it with style and verve. Here, for instance, is Charles Oman (1860-1946) writing of the Spanish royal family in A History of the Peninsular War (seven volumes):

It is perhaps necessary to gain some detailed idea of the unpleasant family party at Madrid. King Charles IV was now a man of sixty years of age: he was so entirely simple and helpless that it is hardly an exaggeration to say that his weakness bordered on imbecility. His elder brother, Don Philip, was so clearly wanting in intellect that he had to be placed in confinement and excluded from the throne. It might occur to us that it would have been well for Spain if Charles had followed him to the asylum, if we had not to remember that the crown would then have fallen to Ferdinand of Naples, who if more intelligent was also more morally worthless than his brother.

. . .

[Charles] may be described as a good-natured and benevolent imbecile: he was not cruel or malicious or licentious, or given to extravagant fancies. . . . He was very ugly, not with the fierce clever ugliness of his father Charles III, but in an imbecile fashion, with a frightfully receding forehead, a big nose, and a retreating jaw generally set in a harmless grin. . . . He had just enough brains to be proud of his position as king, and to resent anything that he regarded as an attack on his dignity -- such as the mention of old constitutional rights and privileges, or any allusion to the Cortes.

A History of the Peninsular War, Volume I (1902), pages 13-14.

Some may think that this type of historical writing is too "subjective" or too "romantic." I respectfully disagree. To my mind, the writing of history in this fashion follows directly in the tradition of Herodotus, who is well-known for his colorful (and often digressive -- though wonderfully so) style.

Goya, "Charles IV" (1789)

Wednesday, June 16, 2010

"I Listen To Money Singing": Philip Larkin And Arthur Schopenhauer

Philip Larkin's "Money" begins with a sardonic (surprise!) reflection by Larkin about how money could allegedly make him happy, if only he could bring himself to spend it on the things that allegedly make us happy. But the poem ends -- and this is why I love Larkin -- with a breathtaking final stanza:

I listen to money singing. It's like looking down

From long french windows at a provincial town,

The slums, the canal, the churches ornate and mad

In the evening sun. It is intensely sad.

High Windows (1974). (An aside that has nothing to do with money: when it comes to final stanzas (or final lines), I humbly suggest that Larkin cannot be surpassed. Consider, for example, "Mr Bleaney," "Continuing to Live," "High Windows," "Dockery and Son," "An Arundel Tomb," "Afternoons," "The Whitsun Weddings," "The Building" -- after reading the closing lines of those poems a few times, you may find that you have memorized them without intending to do so. "On that green evening when our death begins . . .")

But, back to the topic at hand. For some reason, I have the urge to pair Larkin's "Money" with a bit of wisdom from Arthur Schopenhauer:

"Money is human happiness in the abstract; he, then, who is no longer capable of enjoying human happiness in the concrete, devotes his heart entirely to money."

William Hogarth, "The Rake in Bedlam" (1735)

I listen to money singing. It's like looking down

From long french windows at a provincial town,

The slums, the canal, the churches ornate and mad

In the evening sun. It is intensely sad.

High Windows (1974). (An aside that has nothing to do with money: when it comes to final stanzas (or final lines), I humbly suggest that Larkin cannot be surpassed. Consider, for example, "Mr Bleaney," "Continuing to Live," "High Windows," "Dockery and Son," "An Arundel Tomb," "Afternoons," "The Whitsun Weddings," "The Building" -- after reading the closing lines of those poems a few times, you may find that you have memorized them without intending to do so. "On that green evening when our death begins . . .")

But, back to the topic at hand. For some reason, I have the urge to pair Larkin's "Money" with a bit of wisdom from Arthur Schopenhauer:

"Money is human happiness in the abstract; he, then, who is no longer capable of enjoying human happiness in the concrete, devotes his heart entirely to money."

William Hogarth, "The Rake in Bedlam" (1735)

Monday, June 14, 2010

"He Is The Concentration Of All That Is American"

I greatly admire Ulysses S. Grant. Why? A first-hand observer of Grant answers that question much more eloquently than I can. Theodore Lyman served as an aide to Major-General George Meade, commander of the Army of the Potomac. Grant was in the field with the Army from 1864 until the end of the war. Lyman saw Grant nearly every day during that period. In a June 12, 1864, letter to his wife, Lyman wrote of Grant: "He is the concentration of all that is American." (George Agassiz (editor), Meade's Headquarters, 1863-1865: Letters of Colonel Theodore Lyman from The Wilderness to Appomattox (1922), page 156.)

T. Harry Williams writes:

Grant's life is, in some ways, the most remarkable one in American history. There is no other quite like it.

. . .

People were always looking for visible signs of greatness in Grant. Most of them saw none and were disappointed. . . . Charles Francis Adams, Jr., grasped immediately the essence of Grant -- that here was an extraordinary man who looked ordinary. Grant could pass for a "dumpy and slouchy little subaltern," Adams thought, but nobody could watch him without concluding that he was a "remarkable man. . . . in a crisis he is one against whom all around, whether few in number or a great army as here, would instinctively lean. He is a man of the most exquisite judgment and tact."

T. Harry Williams, McClellan, Sherman and Grant (1962), pages 79-83.

As he was dying of cancer, Grant -- in a final act of fortitude and integrity -- wrote his memoirs in order to pay off his debts and to provide for the financial security of his family. He completed the memoirs less than a week before his death.

Grant begins: "My family is American, and has been for generations, in all its branches, direct and collateral."

Grant writing his memoirs

T. Harry Williams writes:

Grant's life is, in some ways, the most remarkable one in American history. There is no other quite like it.

. . .

People were always looking for visible signs of greatness in Grant. Most of them saw none and were disappointed. . . . Charles Francis Adams, Jr., grasped immediately the essence of Grant -- that here was an extraordinary man who looked ordinary. Grant could pass for a "dumpy and slouchy little subaltern," Adams thought, but nobody could watch him without concluding that he was a "remarkable man. . . . in a crisis he is one against whom all around, whether few in number or a great army as here, would instinctively lean. He is a man of the most exquisite judgment and tact."

T. Harry Williams, McClellan, Sherman and Grant (1962), pages 79-83.

As he was dying of cancer, Grant -- in a final act of fortitude and integrity -- wrote his memoirs in order to pay off his debts and to provide for the financial security of his family. He completed the memoirs less than a week before his death.

Grant begins: "My family is American, and has been for generations, in all its branches, direct and collateral."

Grant writing his memoirs

Saturday, June 12, 2010

"Life In A Day"

Life in a day.

-- Louis MacNeice, "Les Sylphides"

Days are where we live.

-- Philip Larkin, "Days"

We two. And nothing in the whole world was lacking.

It is later one realizes. I forget

the exact year or what we said. But the place

for a lifetime glows with noon.

-- Bernard Spencer, "On the Road"

The days that remain with us are rarely the planned-for days or the waited-upon days. The days that remain with us do so unaccountably, unwontedly. Those that remain -- in, say, an angle of light or a color -- are, I think, best left wordless.

'Why, yes, -- we've pass'd a pleasant day,

While life's true joys are on their way.'

-- Ah me! I now look back afar,

And see that one day like a star.

-- William Allingham (1824-1889)

The Spirit's Epochs

Not in the crises of events,

Of compass'd hopes, or fears fulfill'd,

Or acts of grave consequence,

Are life's delight and depth reveal'd.

The day of days was not the day;

That went before, or was postponed;

The night Death took our lamp away

Was not the night on which we groan'd.

I drew my bride, beneath the moon,

Across my threshold; happy hour!

But, ah, the walk that afternoon

We saw the water-flags in flower!

-- Coventry Patmore (1823-1896)

Water-flags

-- Louis MacNeice, "Les Sylphides"

Days are where we live.

-- Philip Larkin, "Days"

We two. And nothing in the whole world was lacking.

It is later one realizes. I forget

the exact year or what we said. But the place

for a lifetime glows with noon.

-- Bernard Spencer, "On the Road"

The days that remain with us are rarely the planned-for days or the waited-upon days. The days that remain with us do so unaccountably, unwontedly. Those that remain -- in, say, an angle of light or a color -- are, I think, best left wordless.

'Why, yes, -- we've pass'd a pleasant day,

While life's true joys are on their way.'

-- Ah me! I now look back afar,

And see that one day like a star.

-- William Allingham (1824-1889)

The Spirit's Epochs

Not in the crises of events,

Of compass'd hopes, or fears fulfill'd,

Or acts of grave consequence,

Are life's delight and depth reveal'd.

The day of days was not the day;

That went before, or was postponed;

The night Death took our lamp away

Was not the night on which we groan'd.

I drew my bride, beneath the moon,

Across my threshold; happy hour!

But, ah, the walk that afternoon

We saw the water-flags in flower!

-- Coventry Patmore (1823-1896)

Water-flags

Thursday, June 10, 2010

Samuel Johnson Runs A Foot-Race

In a previous post, we saw Samuel Johnson suddenly decide to roll sideways down a hill at the country house of Bennet Langton. ("Ludwig Wittgenstein Pretends To Be The Moon. Samuel Johnson Rolls Down A Hill": May 8, 2010.) That Johnson could be so playful and exuberant is something that we should remember, so that we do not accept uncritically the caricature of him as the harrumphing, orotund Great Cham.

"At a gentleman's seat in Devonshire, as he and some company were sitting in a saloon, before which was a spacious lawn, it was remarked as a very proper place for running a race. A young lady present boasted that she could outrun any person; on which Dr. Johnson rose up and said, 'Madam, you cannot outrun me'; and, going out on the lawn, they started. The lady at first had the advantage; but Dr. Johnson happening to have slippers on much too small for his feet, kick'd them off up into the air, and ran a great length without them, leaving the lady far behind him, and, having won the victory, he returned, leading her by the hand, with looks of high exultation and delight."

"Recollections of Dr. Johnson by Miss Reynolds," Johnsonian Miscellanies (edited by George Birkbeck Hill), Volume II (1897), page 278.

Joshua Reynolds, "Samuel Johnson" (c. 1769)

"At a gentleman's seat in Devonshire, as he and some company were sitting in a saloon, before which was a spacious lawn, it was remarked as a very proper place for running a race. A young lady present boasted that she could outrun any person; on which Dr. Johnson rose up and said, 'Madam, you cannot outrun me'; and, going out on the lawn, they started. The lady at first had the advantage; but Dr. Johnson happening to have slippers on much too small for his feet, kick'd them off up into the air, and ran a great length without them, leaving the lady far behind him, and, having won the victory, he returned, leading her by the hand, with looks of high exultation and delight."

"Recollections of Dr. Johnson by Miss Reynolds," Johnsonian Miscellanies (edited by George Birkbeck Hill), Volume II (1897), page 278.

Joshua Reynolds, "Samuel Johnson" (c. 1769)

Tuesday, June 8, 2010

"I'll Chance It, As Old Horne Did His Neck"

The contributors to Notes and Queries -- that repository of out-of-the-way knowledge -- were fond of recording (for the sake of preserving) "English proverbs and proverbial phrases." We earlier met with "like Morley's ducks, born without a notion." I am no doubt in a tiny minority in hoping that these chestnuts do not disappear. You never know when one of them might come in handy. Thus, I give you "old Horne":

"I'll chance it, as old Horne did his neck," or "as parson Horne did his neck." Fifty and sixty years ago this was a common saying in the midland counties, and may be now. I have heard of its being used in Scotland. Horne was a clergyman in Nottinghamshire. Horne committed a murder. He escaped to the Continent. After many years' residence abroad he determined to return. In answer to an attempt to dissuade him, and being told he would be hanged if he did, he said, "I'll chance it." He did return, was tried, condemned, and executed.

Notes and Queries, Fifth Series, Volume X, No. 236 (July 6, 1878), contributed by "Ellcee."

"I'll chance it, as old Horne did his neck," or "as parson Horne did his neck." Fifty and sixty years ago this was a common saying in the midland counties, and may be now. I have heard of its being used in Scotland. Horne was a clergyman in Nottinghamshire. Horne committed a murder. He escaped to the Continent. After many years' residence abroad he determined to return. In answer to an attempt to dissuade him, and being told he would be hanged if he did, he said, "I'll chance it." He did return, was tried, condemned, and executed.

Notes and Queries, Fifth Series, Volume X, No. 236 (July 6, 1878), contributed by "Ellcee."

Sunday, June 6, 2010

At Sea In An Open Boat: Louis MacNeice And W. R. Rodgers

The metaphor of life as a sea voyage is a time-honored one. In these two poems, Louis MacNeice and W. R. Rodgers see it as a perilous voyage in an open boat, amidst looming waves, in an icy sea, beneath a tilting sky . . .

Thalassa

Run out the boat, my broken comrades;

Let the old seaweed crack, the surge

Burgeon oblivious of the last

Embarkation of feckless men,

Let every adverse force converge --

Here we must needs embark again.

Run up the sail, my heartsick comrades;

Let each horizon tilt and lurch --

You know the worst: your wills are fickle,

Your values blurred, your hearts impure

And your past life a ruined church --

But let your poison be your cure.

Put out to sea, ignoble comrades,

Whose record shall be noble yet;

Butting through scarps of moving marble

The narwhal dares us to be free;

By a high star our course is set,

Our end is Life. Put out to sea.

"Thalassa" was found in Louis MacNeice's papers after his death in 1963. The date of its composition is unknown. (An aside: "Thalassa! Thalassa!" (or, "Thalatta! Thalatta!") -- the cry of the Greek mercenaries in Xenophon's Anabasis -- is explored by Tim Rood in his delightful The Sea! The Sea!: The Shout of the Ten Thousand in the Modern Imagination.)

The following poem is by W. R. Rodgers (1909-1969), who, like MacNeice, was born in Northern Ireland. He and MacNeice were acquaintances.

Life's Circumnavigators

Here, where the taut wave hangs

Its tented tons, we steer

Through rocking arch of eye

And creaking reach of ear,

Anchored to flying sky,

And chained to changing fear.

O when shall we, all spent,

Row in to some far strand,

And find, to our content,

The original land

From which our boat once went,

Though not the one we planned.

Us on that happy day

This fierce sea will release,

On our rough face of clay,

The final glaze of peace.

Our oars we all will lay

Down, and desire will cease.

Caspar David Friedrich, "The Sea of Ice" (1824)

Thalassa

Run out the boat, my broken comrades;

Let the old seaweed crack, the surge

Burgeon oblivious of the last

Embarkation of feckless men,

Let every adverse force converge --

Here we must needs embark again.

Run up the sail, my heartsick comrades;

Let each horizon tilt and lurch --

You know the worst: your wills are fickle,

Your values blurred, your hearts impure

And your past life a ruined church --

But let your poison be your cure.

Put out to sea, ignoble comrades,

Whose record shall be noble yet;

Butting through scarps of moving marble

The narwhal dares us to be free;

By a high star our course is set,

Our end is Life. Put out to sea.

"Thalassa" was found in Louis MacNeice's papers after his death in 1963. The date of its composition is unknown. (An aside: "Thalassa! Thalassa!" (or, "Thalatta! Thalatta!") -- the cry of the Greek mercenaries in Xenophon's Anabasis -- is explored by Tim Rood in his delightful The Sea! The Sea!: The Shout of the Ten Thousand in the Modern Imagination.)

The following poem is by W. R. Rodgers (1909-1969), who, like MacNeice, was born in Northern Ireland. He and MacNeice were acquaintances.

Life's Circumnavigators

Here, where the taut wave hangs

Its tented tons, we steer

Through rocking arch of eye

And creaking reach of ear,

Anchored to flying sky,

And chained to changing fear.

O when shall we, all spent,

Row in to some far strand,

And find, to our content,

The original land

From which our boat once went,

Though not the one we planned.

Us on that happy day

This fierce sea will release,

On our rough face of clay,

The final glaze of peace.

Our oars we all will lay

Down, and desire will cease.

Caspar David Friedrich, "The Sea of Ice" (1824)

Friday, June 4, 2010

"No Newspapers"; Or, "Melons Are Crowned By The Crowd"

Although the following two poems are about newspapers, I have no particular axe to grind when it comes to that particular form of news reporting. Rather, the topic at hand is "news" -- whether delivered via newspapers, television, radio, or the Internet.

Let me be clear: I do not claim to maintain an Olympian distance from "news." On the contrary, I bring this topic up because I am often troubled by my concern with "news," and by my habit of letting it work itself into my life. In addition, I have recently been thinking about Thomas Hardy's poem "In Time of 'The Breaking of Nations'" -- "only a man harrowing clods," etc. -- and the perspective that we ought to put on things.

First, Mary Coleridge (1861-1907):

No Newspapers

Where, to me, is the loss

Of the scenes they saw -- of the sounds they heard;

A butterfly flits across,

Or a bird;

The moss is growing on the wall,

I heard the leaf of the poppy fall.

Collected Poems (edited by Theresa Whistler) (1954).

Yes, sentimental and Victorian. Well, then, if it is vitriol that you want, let us proceed to Stephen Crane:

A newspaper is a collection of half-injustices

Which, bawled by boys from mile to mile,

Spreads its curious opinion

To a million merciful and sneering men,

While families cuddle the joys of the fireside

When spurred by tale of dire lone agony.

A newspaper is a court

Where every one is kindly and unfairly tried

By a squalor of honest men.

A newspaper is a market

Where wisdom sells its freedom

And melons are crowned by the crowd.

A newspaper is a game

Where his error scores the player victory

While another's skill wins death.

A newspaper is a symbol;

It is feckless life's chronicle,

A collection of loud tales

Concentrating eternal stupidities,

That in remote ages lived unhaltered,

Roaming through a fenceless world.

The Poems of Stephen Crane (edited by Joseph Katz) (1966).

Luis Melendez (1716-1780), "Still Life with Melon and Pears"

Let me be clear: I do not claim to maintain an Olympian distance from "news." On the contrary, I bring this topic up because I am often troubled by my concern with "news," and by my habit of letting it work itself into my life. In addition, I have recently been thinking about Thomas Hardy's poem "In Time of 'The Breaking of Nations'" -- "only a man harrowing clods," etc. -- and the perspective that we ought to put on things.

First, Mary Coleridge (1861-1907):

No Newspapers

Where, to me, is the loss

Of the scenes they saw -- of the sounds they heard;

A butterfly flits across,

Or a bird;

The moss is growing on the wall,

I heard the leaf of the poppy fall.

Collected Poems (edited by Theresa Whistler) (1954).

Yes, sentimental and Victorian. Well, then, if it is vitriol that you want, let us proceed to Stephen Crane:

A newspaper is a collection of half-injustices

Which, bawled by boys from mile to mile,

Spreads its curious opinion

To a million merciful and sneering men,

While families cuddle the joys of the fireside

When spurred by tale of dire lone agony.

A newspaper is a court

Where every one is kindly and unfairly tried

By a squalor of honest men.

A newspaper is a market

Where wisdom sells its freedom

And melons are crowned by the crowd.

A newspaper is a game

Where his error scores the player victory

While another's skill wins death.

A newspaper is a symbol;

It is feckless life's chronicle,

A collection of loud tales

Concentrating eternal stupidities,

That in remote ages lived unhaltered,

Roaming through a fenceless world.

The Poems of Stephen Crane (edited by Joseph Katz) (1966).

Luis Melendez (1716-1780), "Still Life with Melon and Pears"

Wednesday, June 2, 2010

Thomas Hardy: June 2, 1840

Thomas Hardy was born on this date 170 years ago.

In Time of 'The Breaking of Nations'

I.

Only a man harrowing clods

In a slow silent walk

With an old horse that stumbles and nods

Half asleep as they stalk.

II.

Only thin smoke without flame

From the heaps of couch-grass;

Yet this will go onward the same

Though Dynasties pass.

III.

Yonder a maid and her wight

Come whispering by:

War's annals will cloud into night

Ere their story die.

John Constable, "Gillingham Bridge, Dorset" (1823)

The banded ones were all dressed in white gowns -- a gay survival from Old Style days, when cheerfulness and May-time were synonyms -- days before the habit of taking long views had reduced emotion to a monotonous average.

-- Tess of the d'Urbervilles

John Constable, "Weymouth Bay from the Downs above

Osmington Mills, Dorset" (c. 1816)

Waiting Both

A star looks down at me,

And says: 'Here I and you

Stand, each in our degree:

What do you mean to do, --

Mean to do?'

I say: 'For all I know,

Wait, and let Time go by,

Till my change come.' -- 'Just so,'

The star says: 'So mean I: --

So mean I.'

In Time of 'The Breaking of Nations'

I.

Only a man harrowing clods

In a slow silent walk

With an old horse that stumbles and nods

Half asleep as they stalk.

II.

Only thin smoke without flame

From the heaps of couch-grass;

Yet this will go onward the same

Though Dynasties pass.

III.

Yonder a maid and her wight

Come whispering by:

War's annals will cloud into night

Ere their story die.

John Constable, "Gillingham Bridge, Dorset" (1823)

The banded ones were all dressed in white gowns -- a gay survival from Old Style days, when cheerfulness and May-time were synonyms -- days before the habit of taking long views had reduced emotion to a monotonous average.

-- Tess of the d'Urbervilles

John Constable, "Weymouth Bay from the Downs above

Osmington Mills, Dorset" (c. 1816)

Waiting Both

A star looks down at me,

And says: 'Here I and you

Stand, each in our degree:

What do you mean to do, --

Mean to do?'

I say: 'For all I know,

Wait, and let Time go by,

Till my change come.' -- 'Just so,'

The star says: 'So mean I: --

So mean I.'