Fortunately, we have it in our power to shut out the noise. Right at this moment. To cite but one example: pay no attention to the News of the World. It is easily done. Turning off the internal noise is much more difficult. Often, at the start of my daily walk, I say to myself: "No thinking." I inevitably fail.

T'ao Yüan-ming (whose nom de plume was "T'ao Ch'ien," meaning, roughly, "the Recluse") left his position in government to live in the countryside. His was not a life of comfortable retreat: he worked as a farmer and had a large family. His poetry reflects a sense of contentment and tranquility, with occasional bumps in the road (the inevitable consequence of making one's living as a farmer).

I built my hut in a place where people live,

and yet there's no clatter of carriage or horse.

You ask me how that could be?

With a mind remote, the region too grows distant.

I pick chrysanthemums by the eastern hedge,

see the southern mountain, calm and still.

The mountain air is beautiful at close of day,

birds on the wing coming home together.

In all this there's some principle of truth,

but try to define it and you forget the words.

T'ao Ch'ien (365-427) (translated by Burton Watson), in Burton Watson, The Columbia Book of Chinese Poetry: From Early Times to the Thirteenth Century (Columbia University Press 1984). The poem is untitled.

The truths that one finds in poetry are not limited to a particular place or time. A conversation between T'ao Ch'ien, a Chinese poet of the 4th and 5th centuries, and Walter de la Mare, an English poet of the 20th century, may, I hope, demonstrate the universality of poetic truth. Think of de la Mare's poems in this post as both a counterpoint to, and an echo of, T'ao Ch'ien's poem.

Days and Moments

The drowsy earth, craving the quiet of night,

Turns her green shoulder from the sun's last ray;

Less than a moment in her solar flight

Now seems, alas! thou fleeting one, life's happiest day.

Walter de la Mare, Inward Companion and Other Poems (Faber and Faber 1950).

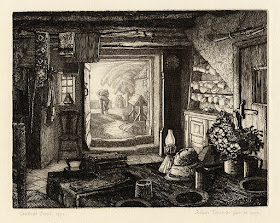

Robin Tanner, "The Gamekeeper's Cottage" (1928)

T'ao Ch'ien possessed deep knowledge of Taoism. Hence, it is not surprising that the final two lines of his poem are reminiscent of Lao Tzu's well-known statement from the Tao te Ching (as translated by Arthur Waley): "Those who know do not speak; those who speak do not know." Here is another translation of T'ao Ch'ien's poem:

I have built my cottage amid the realm of men

But I hear no din of horses or carriages.

You might ask, "How is this possible?"

A remote heart creates its own hermitage!

Picking chrysanthemums by the eastern hedge,

I perceive the Southern Mountain in the distance.

Marvelous is the mountain air at sunset!

The flitting birds return home in pairs,

In these things is the essence of truth --

I wish to explain but have lost the words.

T'ao Ch'ien (translated by Angela Jung Palandri), in Angela Jung Palandri, "The Taoist Vision: A Study of T'ao Yüan-ming's Nature Poetry," Journal of Chinese Philosophy, Volume 15 (1988).

Some truths cannot be put into words. These truths are usually the most important truths. "Forget[ting] the words" or "los[ing] the words" is not necessarily a bad thing: it may be a sign that you have learned something important. An observation by Ludwig Wittgenstein (which has appeared here on more than one occasion) complements Lao Tzu and T'ao Ch'ien quite well: "What we cannot speak about we must pass over in silence." Ludwig Wittgenstein (translated by David Pears and Brian McGuinness), Proposition 7, Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus (1922).

Solitude

Space beyond space: stars needling into night:

Through rack, above, I gaze from Earth below --

Spinning in unintelligible quiet beneath

A moonlit drift of cloudlets, still as snow.

Walter de la Mare, Inward Companion and Other Poems (Faber and Faber 1950).

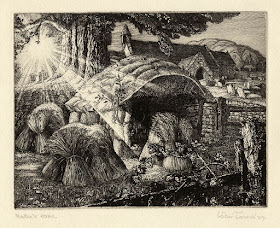

Robin Tanner, "June" (1946)

The fourth line of T'ao Ch'ien's poem contains the Chinese character xin. The same character is known as kokoro in Japanese. The character is a wonderful one: in both Chinese and Japanese it can mean "heart," but it can also mean "mind." It can also carry connotations of "spirit," "soul," or "core," which seems appropriate: heart-mind; mind-heart. That evanescent and ungraspable thing. Animula vagula blandula.

Burton Watson elects to translate xin as "mind," as does David Hinton in the following translation of the poem. Palandri, on the other hand, translates xin as "heart." Arthur Waley, who produced the first translation of this poem into English (which appears at the end of this post), also elects to use "heart." This division of opinion suggests that we have no word in English to match the beauty, implication, and subtlety of xin (or kokoro).

I live here in a village house without

all that racket horses and carts stir up,

and you wonder how that could ever be.

Wherever the mind dwells apart is itself

a distant place. Picking chrysanthemums

at my east fence, I see South Mountain

far off: air lovely at dusk, birds in flight

returning home. All this means something,

something absolute: whenever I start

to explain it, I forget words altogether.

T'ao Ch'ien (translated by David Hinton), in David Hinton, Mountain Home: The Wilderness Poetry of Ancient China (Counterpoint 2002).

Unforeseen

Darkness had fallen. I opened the door:

And lo, a stranger in the empty room --

A marvel of moonlight upon wall and floor . . .

The quiet of mercy? Or the hush of doom?

Walter de la Mare, Memory and Other Poems (Constable 1938).

Robin Tanner, "Martin's Hovel" (1927)

"Admirable is a person who has nothing that hampers his mind." Bashō (translated by Makoto Ueda), in Makoto Ueda, Matsuo Bashō (Twayne 1970), page 118. And why not this as well, given our consideration of xin and kokoro: "Admirable is a person who has nothing that hampers his heart." Perhaps this is what T'ao Ch'ien is getting at in line 4: "a mind remote" (Watson); "a remote heart" (Palandri); "the mind dwells apart" (Hinton). And, from Arthur Waley in the translation below: "a heart that is distant."

I built my hut in a zone of human habitation,

Yet near me there sounds no noise of horse or coach.

Would you know how that is possible?

A heart that is distant creates a wilderness round it.

I pluck chrysanthemums under the eastern hedge,

Then gaze long at the distant summer hills.

The mountain air is fresh at the dusk of day;

The flying birds two by two return.

In these things there lies a deep meaning;

Yet when we would express it, words suddenly fail us.

T'ao Ch'ien (translated by Arthur Waley), in Arthur Waley, One Hundred and Seventy Chinese Poems (Constable 1918).

This remoteness or distance of heart or mind is not a matter of coldness, indifference, or self-absorption. It is a matter of the mind or the heart not being hampered or stifled by the noise of the World, and by the noise that comes from within our ever-buzzing brain. "Words exist because of meaning; once you've gotten the meaning, you can forget the words. Where can I find a man who has forgotten words so I can have a word with him?" Chuang Tzu (translated by Burton Watson), in Burton Watson, Chuang Tzu: Basic Writings (Columbia University Press 1964), page 140.

Night

That shining moon -- watched by that one faint star:

Sure now am I, beyond the fear of change,

The lovely in life is the familiar,

And only the lovelier for continuing strange.

Walter de la Mare, Memory and Other Poems (Constable 1938).

Robin Tanner, "The Wicket Gate" (1977)

stunningly good... i like this one:

ReplyDeletei'm twenty-seven years

and always sought the Way.

well, this morning we passed

like strangers on the road.

Kokuin, 10 c. (trans stryk/ikemoto, zen poems of china and japan)

Mudpuddle: Thank you very much for your kind words about the post. And thank you as well for the poem by Kokuin, which is apt in this context. I appreciate your stopping by again.

ReplyDeleteI take the point you are making but do think Walter de la Mare can do much better than the quatrains you quote!

ReplyDeleteThe Silence - Poem by Wendell Berry

ReplyDeleteThough the air is full of singing

my head is loud

with the labor of words.

Though the season is rich

with fruit, my tongue

hungers for the sweet of speech.

Though the beech is golden

I cannot stand beside it

mute, but must say

'It is golden,' while the leaves

stir and fall with a sound

that is not a name.

It is in the silence

that my hope is, and my aim.

A song whose lines

I cannot make or sing

sounds men's silence

like a root. Let me say

and not mourn: the world

lives in the death of speech

and sings there.

Mr. Medlin: It's very nice to hear from you again. I'm afraid we are of opposite views when it comes to de la Mare's quatrain poems: I'm quite fond of them. In fact, I sometimes return to his Collected Poems solely to read his four-line poems. (I even counted them once: there are 39 of them in the Collected Poems.) But that's the way these things go. I'm sure we both agree that he is a wonderful poet who wrote many wonderful poems. And that is all that matters.

ReplyDeleteThank you very much for visiting again.

Anonymous: Thank you very much for sharing Berry's poem, which is new to me. It is lovely, and it fits perfectly here. Thanks again.

ReplyDeleteYes, it's fascinating how people can disagree on specifics whilst agreeing on an overall view of a poet. I might mention that noting your approbations of Wallace Stevens over the past couple of years - a poet I had barely noticed and had a very negative view of - I just the other day bought a copy of his Collected Poems - well it was second-hand and going for a song - and I shall start to read him shortly. It will be interesting to find whether my instinctive view of his work changes as I come to know it much better.

ReplyDeleteMr. Medlin: Thank you for your follow-up thoughts. At the risk of being annoying, I cannot resist providing a list of my favorite poems by Stevens, bearing two things in mind: (1) it is always exciting to browse at whim and (2) you and I may, as with de la Mare's four-line poems, see things differently (which is perfectly fine). In no particular order, but as they come to mind, I respectfully suggest the following (most, if not all, of which have appeared here in the past): "The River of Rivers in Connecticut," "This Solitude of Cataracts," "The Poem that Took the Place of a Mountain," "A Rabbit as King of the Ghosts," "The House Was Quiet and the World Was Calm," "Autumn Refrain," "The Region November," "The Course of a Particular," "The Plain Sense of Things," "A Quiet Normal Life." Feel free to completely disregard my suggestions, of course!

ReplyDeleteFor some reason, Stevens never seems to have caught on in the UK (as opposed to being an academic cottage industry over here). But I think that one of the best contemplations on Stevens's attractions was written by Roy Fuller: an essay titled "Both Pie and Custard," which may be found in his Owls and Artificers: Oxford Lectures on Poetry (Andre Deutsch 1971). (Which is a delightful book as a whole, by the way.) You may already be familiar with both the essay and the book. If not, I highly recommend both. Another Englishman who has written well on Stevens is Frank Kermode (again, as you may already know).

Thank you very much for stopping by again.

It's interesting -- & wonderful -- to me that Robin Tanner's engravings in this post cover a 50-year period. At my age of 78, I feel inspired by the idea of an artist creating such fine works for fifty years.

ReplyDeleteHave a lovely summer, Susan

Many thanks for your Stevens list. Because of other commitments I shall have to read Stevens a few poems at a time over several months - perhaps no bad thing. So it will be ages before I am ready to 'prognosticate'. Ah, Roy Fuller, yet another fine poet and critic now largely forgotten. I knew him tangentially; I was active at the Poetry Society in London during the 1980s and he was a regular reader on the poetry circuit having retired from his job as (famously!) a director of the Woolwich Building Society. And there, of course, he shares a great similarity with Wallace Stevens.

ReplyDeleteJust a brief note of deep appreciation for the delightful discoveries I make through each of your postings.

ReplyDeleteSusan: It's very nice to hear from you again. I hadn't thought of that aspect of Tanner's work -- and I should have. I was thinking something along the lines you suggest when I was recently reading Thomas Hardy's poems: he was writing wonderful poems up until his death at the age of 87. What a marvelous thing!

ReplyDeleteI think that Tanner remained true to his Muse throughout his life, although Samuel Palmer's influence is perhaps more evident in his earlier works than in his later works. But his theme is consistent and constant: his love of the English countryside. All his work is beautiful, from beginning to end.

As always, thank you very much for visiting. I hope that you have a lovely summer as well.

Mr. Medlin: I had forgotten about Fuller's "day job": thank you for reminding me. As you say, an interesting parallel.

ReplyDeleteYour schedule for reading Stevens is a good one: "a few poems at a time over several months" is perfect -- it gives them time to sink in.

Thank you again for the follow-up thoughts.

Ms. Westerhout: That's very nice of you to say. Sometimes I feel that I have exhausted the contents of my mind, so a comment such as yours is greatly appreciated. Thank you very much.

ReplyDelete