"A thing is beautiful to the extent that it does not let itself be caught."

Philippe Jaccottet (translated by John Taylor), from "Blazon in Green and White" ("Blason Vert et Blanc"), in Philippe Jaccottet, And, Nonetheless: Selected Prose and Poetry 1990-2009 (Chelsea Editions 2011), page 53.

On a late afternoon this past week I walked between two meadows. The meadow on my left, the parade ground of a former army post, was open and expansive. It has been mown recently, and the winter rains have turned it deep green. On my right, a broad field of brown and gray wild grasses sloped down to the bluffs above Puget Sound.

The afternoon was windless and quiet. The declining sun was hidden behind a flat layer of motionless grey clouds out over the Sound, stretching away to the Olympic Mountains in the west. Throughout my walk, my eyes kept returning to a glowing patch of pale yellow in the center of the cloud blanket, above, and dimly reflected in, the dark water below.

As I gazed at the patch yet again, I suddenly heard behind and above me a tiny creaking of wings. A dozen or so sparrows soon flew over me with the sound of a soft rush of wind. And those lovely creaking wings. I lost sight of the sparrows as they disappeared into the woods up ahead.

Beauty

What does it mean? Tired, angry, and ill at ease,

No man, woman, or child alive could please

Me now. And yet I almost dare to laugh

Because I sit and frame an epitaph --

'Here lies all that no one loved of him

And that loved no one.' Then in a trice that whim

Has wearied. But, though I am like a river

At fall of evening while it seems that never

Has the sun lighted it or warmed it, while

Cross breezes cut the surface to a file,

This heart, some fraction of me, happily

Floats through the window even now to a tree

Down in the misting, dim-lit, quiet vale,

Not like a pewit that returns to wail

For something it has lost, but like a dove

That slants unswerving to its home and love.

There I find my rest, and through the dusk air

Flies what yet lives in me. Beauty is there.

Edward Thomas, in Edna Longley (editor), Edward Thomas: The Annotated Collected Poems (Bloodaxe Books 2008).

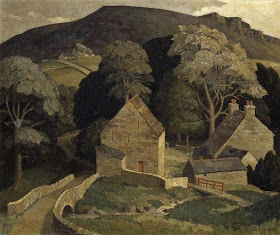

Eric Hesketh Hubbard (1892-1957), "The Cuckmere Valley, East Sussex"

A sparrow flying overhead is entirely and exactly what it is: a sparrow flying overhead. And yet . . .

"It is possible that beauty is born when the finite and the infinite become visible at the same time, that is to say, when we see forms but recognize that they do not express everything, that they do not stand only for themselves, that they leave room for the intangible."

Philippe Jaccottet (translated by Tess Lewis), in Philippe Jaccottet, Seedtime: Notebooks, 1954-1979 (Seagull Books 2013), page 38.

One needn't be a mystic or an eremite in order to sense that we live in a World of immanence: that, although each of the particulars of the World is wholly sufficient in and of itself, each of those particulars contains a hint of something that lies behind it and beyond it. Something "intangible," to use Jaccottet's word. Those who have been thoroughly modernized are wont to grow nervous at talk of a World of immanence. This is perfectly fine. I am not out to convert anyone to my sense of the World. We each feel what we feel, and there is no accounting for it.

The One

Green, blue, yellow and red --

God is down in the swamps and marshes,

Sensational as April and almost incred-

ible the flowering of our catharsis.

A humble scene in a backward place

Where no one important ever looked;

The raving flowers looked up in the face

Of the One and the Endless, the Mind that has baulked

The profoundest of mortals. A primrose, a violet,

A violent wild iris -- but mostly anonymous performers,

Yet an important occasion as the Muse at her toilet

Prepared to inform the local farmers

That beautiful, beautiful, beautiful God

Was breathing His love by a cut-away bog.

Patrick Kavanagh, Come Dance with Kitty Stobling and Other Poems (Longmans 1960).

Malcolm Midwood Milne, "Barrow Hill" (1939)

Patrick Kavanagh tells us that "God is down in the swamps and marshes." Any talk of immanence tends to provoke our human tendency to put a name to things. Speaking solely for myself, I do not find this necessary. However, I have no objection whatsoever to Kavanagh (or anybody else) finding God in "a cut-away bog." I think it is a beautiful thought, and it is entirely plausible.

As kingfishers catch fire, dragonflies draw flame;

As tumbled over rim in roundy wells

Stones ring; like each tucked string tells, each hung bell's

Bow swung finds tongue to fling out broad its name;

Each mortal thing does one thing and the same:

Deals out that being indoors each one dwells;

Selves -- goes itself; myself it speaks and spells,

Crying What I do is me: for that I came.

I say more: the just man justices;

Keeps grace: that keeps all his goings graces;

Acts in God's eye what in God's eye he is --

Christ. For Christ plays in ten thousand places,

Lovely in limbs, and lovely in eyes not his

To the Father through the features of men's faces.

Gerard Manley Hopkins, in W. H. Gardner and N. H. MacKenzie (editors), The Poems of Gerard Manley Hopkins (Oxford University Press 1967). The poem is untitled.

Hopkins's vision of immanence is an ecstatic vision, and this is reflected in the extravagance of his language. So unique is his vision that he felt compelled to invent the terms "inscape" and "instress" to articulate his sense of immanence. "Inscape" may be described as "the 'individually-distinctive' inner essence or 'pattern' of a thing (an object, whether a tree, a flower, or a sonnet; a person; a scene)." Lesley Higgins (editor), The Collected Works of Gerard Manley Hopkins, Volume III: Diaries, Journals, and Notebooks (Oxford University Press 2015), page 1, footnote 1 (quoting Hopkins). "Instress" is "the force emanating from or expressed by the object, which the sensitive viewer can apprehend." Ibid. (For an introduction to the concepts of "inscape" and "instress," please see W. H. Gardner, "Gerard Manley Hopkins and the Poetry of Inscape," Theoria: A Journal of Social and Political Theory, Number 33 (October 1969), pages 1-16.)

With "inscape" and "instress" in mind, lines such as "Each mortal thing does one thing and the same:/Deals out that being indoors each one dwells," "Selves -- goes itself; myself it speaks and spells," and "Crying What I do is me: for that I came" become less obscure. But Hopkins's vision of immanence is perhaps best expressed in "Keeps grace: that keeps all his goings graces" and "Christ plays in ten thousand places." With respect to the phrase "ten thousand places," it is worth noting that the formulation "the ten thousand things" is used in Buddhism and Taoism to describe the variousness of the World, and is often found in Chinese and Japanese poetry. Hopkins's Christ of "ten thousand places" is, of course, Catholic (Jesuitical, and seasoned with the thoughts of Duns Scotus and of the Greek philosophers). Yet, as I suggested above, a World of immanence transcends both the names we place on things and our human systems of thought.

George Mackley (1900-1983), "Brackie's Burn, Northumberland"

Any hint of immanence is a matter of the passing moment: evanescent, and vanishing even as we sense it.

"All I have been able to do is to walk and go on walking, remember, glimpse, forget, try again, rediscover, become absorbed. I have not bent down to inspect the ground like an entomologist or a geologist; I've merely passed by, open to impressions. I have seen those things which also pass -- more quickly or, conversely, more slowly than human life. Occasionally, as if our movements had crossed -- like the encounter of two glances that can create a flash of illumination and open up another world -- I've thought I had glimpsed what I should have to call the still centre of the moving world. Too much said? Better to walk on . . ."

Philippe Jaccottet (translated by Mark Treharne), Landscapes with Absent Figures (Paysages avec Figures Absentes) (Delos Press/Menard Press 1997), page 4. The ellipses appear in the original text.

How could it be otherwise? Why would we want it otherwise? This is how we receive our gifts.

First Known When Lost

I never had noticed it until

'Twas gone, -- the narrow copse

Where now the woodman lops

The last of the willows with his bill.

It was not more than a hedge overgrown.

One meadow's breadth away

I passed it day by day.

Now the soil is bare as a bone,

And black betwixt two meadows green,

Though fresh-cut faggot ends

Of hazel make some amends

With a gleam as if flowers they had been.

Strange it could have hidden so near!

And now I see as I look

That the small winding brook,

A tributary's tributary, rises there.

Edward Thomas, in Edna Longley (editor), Edward Thomas: The Annotated Collected Poems (Bloodaxe Books 2008).

James Torrington Bell, "Braes of Downie" (1938)

Edward Thomas, Hopkins, Kavinaugh--thanks for bringing them together for us this morning. Also Phillippe Jaccottet, whom I haven't read before. I should read this post every morning, or something like it. Strange how poems in books and paintings in museums become new and important again when they are isolated and framed, as you did here. Gratefully,

ReplyDeleteAnonymous: Thank you very much for your kind words about the post. I'm pleased you liked it. I agree with your thought about viewing poems and paintings (or any work of art) in a new context. All of my posts are a case of one thing leading to another. It is a matter of happenstance and of a rediscovery of things as they are placed side by side with other things in a new pattern. For me, making these connections may help to refresh, or alter, one's thoughts about something that seems familiar. At least that's the hope.

ReplyDeleteThank you for visiting, and for sharing your thoughts.

Tangential to your blog entry, but perhaps appropriate for citation here, is this passage from Santayana, as quoted by Owen Barfield in his book Poetic Diction:

ReplyDelete"Men are habitually insensible to beauty. Tomes of aesthetic criticism hang on a few moments of real delight and intuition. It is in rare and scattered instants that beauty smiles even on her adorers, who are reduced for habitual comfort to remembering her past favours. An aesthetic glow may pervade experience, but that circumstance is seldom remarked; it figures only as an influence working subterraneously on thoughts and judgements which in themselves take a cognitive or practical direction. Only when the aesthetic ingredient becomes predominant do we exclaim, How beautiful! Ordinarily the pleasures which formal perception gives remain an undistinguished part of our comfort or curiosity.

"Taste is formed in those moments when aesthetic emotion is massive and distinct; preferences then grow conscious, judgements then put into words will reverberate through calmer hours; they will constitute prejudices, habits of apperception, secret standards for all other beauties. A period of life in which such intuitions have been frequent may amass tastes and ideals sufficient for the rest of our days. Youth in these matters governs maturity, and while men may develop their early impressions more systematically and find confirmations of them in various quarters, they will seldom look at the world afresh or use new categories in deciphering it. Half our standards come from our first masters, and the other half from our first loves. Never being so deeply stirred again, we remain persuaded that no objects save those we then discovered can have a true sublimity….Thus the volume and intensity of some appreciations, especially when nothing of the kind has preceded, makes them authoritative over our subsequent judgments. On those warm moments hang all our cold systematic opinions; and while the latter fill our days and shape our careers it is only the former that are crucial and alive."

Stephen, a lovely description of your walk, very evocative.

ReplyDeleteA few days ago I had to attend a meeting that involved walking through quite an impoverished and run down inner city area, part of which led me to cross a bridge over a river confined between factories and the backs of houses.

The river bank and river itself were badly littered with all manner of rubbish. It was a depressingly sad picture and yet suddenly there, floating toward me were two swans, a cygnet and from the river bank came the familiar song of a robin.

Even here in this neglected place there was a moment of beauty, though sad to see these beautiful creatures in such a place.

I stood awhile on the bridge and thought in spite of the dreariness of the surroundings, the glimpse of those swans and those familiar notes seemed to tell of something not utterly contained or defined by this depleted landscape.

People passed, crossing the bridge, no one paused,or stopped to look, and I thought how sad it is that people have forgotten to notice, though living or working in such a place I understand why. But here too there is something persisting, here in this place, connected, indefinably to an otherness, sustaining this and beyond it.Visible in these remarkable moments,the multiplicity of this world.

Wurmbrand: Thank you for the passage from Santayana, which is new to me and apt. I regret my lack of knowledge of his writings, although I have come across excerpts over the years, and they always make good sense. I understand his point about our aesthetic judgments and appreciations being developed in our youth, but I wonder if he doesn't overstate the case a bit. I particularly wonder about "Never being so deeply stirred again . . ." I would agree that our passions, in general, run higher in youth (which is why a great deal of the best lyric poetry is written when poets are younger, although there are exceptions: Hardy, Yeats, Stevens), but I'm not convinced that we are "never . . . so deeply stirred again." But perhaps I'm merely being defensive about growing old!

ReplyDeleteThank you very much for visiting again. and for sharing this.

John: Thank you very much for those lovely thoughts. As you and I have discussed here before, we always need to be paying attention, don't we? Your encounter with the swans and the robin in that environment is a perfect example. Patrick Kavanagh's "The Hospital," which I'm sure you are familiar with, comes to mind. It begins: "A year ago I fell in love with the functional ward/Of a chest hospital . . .," and ends: "Naming these things is the love-act and its pledge;/For we must record love's mystery without claptrap,/Snatch out of time the passionate transitory." I would equate "the passionate transitory" with the beauty we are able to encounter on a daily basis.

ReplyDeleteYour observation about the swans going unnoticed brought to mind a poem by Po Chü-i, as translated by Arthur Waley. The title is: "Passing T'ien-Men Street in Ch'ang-an and Seeing a Distant View of Chung-nan Mountains."

The snow has gone from Chung-nan; spring is almost come.

Lovely in the distance its blue colours, against the brown of the streets.

A thousand coaches, ten thousand horsemen pass down the Nine Roads;

Turns his head and looks at the mountains -- not one man!

As ever, thank you for visiting, and for sharing your thoughts.

Stephen, Thank you for the Po Chu-i poem, which is beautiful and entirely new to me.

ReplyDeleteJohn: You're welcome. It's one of those poems that has stayed with me over the years, and I thought it was a nice complement to your thoughts. Take care.

ReplyDeleteLove to read your blog. Especially enjoy the paintings too.

ReplyDeleteThanks, Stephen for your care and effort.

Stowey: Thank you very much. I greatly appreciate your kind words. I'm happy to have you as a visitor, and I hope you will keep returning. Thanks again.

ReplyDeletei don't know... - i always find myself breathless when walking and thinking with jaccottet. one could spend one's life with the first quote (only a sentence long!), "A thing is beautiful to the extent that it does not let itself be caught." but then when you go on, or he goes on, i am so caught up in his wonder and excruciating care to understand, i am drunk on and with him again, "It is possible that beauty is born when the finite and the infinite become visible at the same time, that is to say, when we see forms but recognize that they do not express everything, that they do not stand only for themselves, that they leave room for the intangible."

ReplyDeletei have only become so lost and found in reading from senancour's "oberman,"The day was dull and somewhat cold; I was feeling nothing else. I passed some flowers set out on a wall breast-high. A single jonquil was in bloom. It is the strongest expression of desire, and it was the first fragrance of the year. I caught a glimpse of all happiness meant for man. That indescribable harmony of creation, the vision of the ideal world, was rounded to completeness within me; I have never felt anything so sudden and inspiring. I should be at a loss to say what form, what likeness, what subtle association it was suggested to me in this flower an illimitable beauty, the expression, the refinement, the pose of a happy, artless woman in all the grace and splendour of the days of love. I cannot picture to myself that power, that vastness which nothing concrete can display; that form which nothing can reveal; that conception of a better world which may be felt, but never found in Nature; that heavenly radiance which we think to grasp, which captivates and enthrals us, and which is but an intangible phantom, wandering astray in depths of gloom."

might we be afraid of immanence for fear of being proved wrong? prove immanence wrong then. i will yet be drunk on something.

also, i can't help but mention a scene in anna karenina which i am just reading. have you read it? a moment when the character Levin gives himself over to living unconsciously and he is flooded with beauty and completeness (just having read wallace stevens' "on the road home" this morning i feel flooded with the confluence of all these scenes),

ReplyDelete"He spent the rest of the time walking about the streets....And never again did he see what he saw then. He was moved in particular by two children going to school, some silvery gray pigeons that flew down from the rooftop to the pavement, and some little loaves of bread, sprinkled with flour, that some invisible hand had set out in front of a bakery. These loaves, pigeons, and two little boys seemed unearthly. It all happened at the same time: a little boy ran over to a pigeon, glancing over at Levin with a smile; the pigeon flapped its wings and fluttered, gleaming in the sunshine among the snowdust quivering in the air, while the smell of freshly baked bread was wafted out of a little window as the loaves were put out. All this together was so extraordinarily wonderful that Levin burst out laughing and crying for joy."

erin: Thank you very much for sharing your thoughts, as well as the wonderful passages from Senancour and Tolstoy.

ReplyDeleteI agree with you entirely about Jaccottet. I just wish that my French language education hadn't ended in my freshman year of college: I am dependent upon translations, and there are still large parts of his work that have not been translated into English. Still, a few fine translations of his prose have appeared in recent years, and these have become very important to me. I agree with you: a sentence or so from him is often enough to preoccupy one for quite some time. His way of looking at the world is inspiring and moving.

The excerpt from Obermann sounds like Jaccottet in places, particularly the passage near the end, beginning "I cannot picture to myself that power . . ." (Although with more Romantic flourishes.) I have never read Senancour, but I have long been intending to do so after reading Matthew Arnold's poems "Obermann" and "Obermann Once More," which you are no doubt familiar with.

I'm embarrassed to say that I have never read Anna Karenina. The passage that you quote is marvelous. This is how these glimpses of "the infinite" tend to occur, I think -- not necessarily on mountain tops or watching the sun sink magnificently into the sea. The commonplace (and I don't use that word pejoratively) is where the infinite -- and the immanent -- resides: the gray pigeons, the loaves of bread, the boys, and "the snow dust quivering in the air." Lovely.

"On the Road Home" is lovely as well. Stevens's thoughts and feelings on "immanence" are hard to pin down, aren't they? Despite his "Nothing that is not there and the nothing that is," and his emphasis on the primacy of the human imagination, I still think that he leaves room for immanence and the infinite. But I may be entirely wrong.

Thank you for visiting again, and for your thought-provoking comments. I always appreciate hearing from you.

I found a copy of this among my papers yesterday. It seems to fit in here well.

ReplyDeleteSusan

The Just

Jorge Luis Borges

A man who cultivates his garden, as Voltaire wished.

He who is grateful for the existence of music.

He who takes pleasure in tracing an etymology.

Two workmen playing, in a café in the South,

a silent game of chess.

The potter, contemplating a color and a form.

The typographer, who sets the page well, though

it may not please him.

A woman and a man, who read the last tercets

of a certain canto.

He who strokes a sleeping animal.

He who justifies, or wishes to, a wrong done him.

He who is grateful for the existence of Stevenson.

He who prefers others to be right.

These people, unaware, are saving the world.

(Borges had a great admiration for the works of R.L. Stevenson.)

Susan: Thank you very much for sharing "The Just." I agree that it goes well with the post, and with the comments that have followed. "These people, unaware, are saving the world" is perfect.

ReplyDeleteBorges's lists and catalogues are wonderful, aren't they? I also like the way he honors his favorite writers in his poems and other writings -- as you point out, Stevenson in this case. By the way, this poem is one of my favorites by Borges; it appeared here back on June 22, 2014, with Stevens's "A Quiet Normal Life." I greatly appreciate your sharing it at this time.

Thank you very much for visiting again. It is always a delight to hear from you. Take care.

Many, perhaps all, of Borges' instances relate to gratitude.

ReplyDeleteIn some sense, gratitude does save the world.

Wurmbrand: Excellent, and lovely, observation. As you know, I often refer to gratitude here, but not as often as I should. Thus, for example, reading Marcus Aurelius (as I have been lately), I am always struck by his repeated injunctions to pay heed to NOW, for time is short. In doing so, one should inevitably feel gratitude for the World and for our existence in it. Or so it seems to me.

ReplyDeleteRegarding your reference to Borges' examples, I realize that what you say is true of all of his "catalog" and "list" poems. I pulled out his Selected Poems after reading Susan's comment. Leafing through it a moment ago, I noticed, in addition to "The Just," "Shinto," "Things," and "Fame," all of which are expressions of things for which he is grateful. And there are others that I have no doubt missed.

As always, thank you very much for sharing your thoughts, and for visiting. It's good to hear from you again.