I am content to live my life in accordance with certain truisms. For instance: Human nature has never changed, and never will. And one of its corollaries: Yet man is born unto trouble, as the sparks fly upward. Both of these seem quite apt in light of the events of the past week.

I suspect that the utility of truisms becomes more apparent as one ages. This is not necessarily a matter of attaining wisdom (I can attest to that). Rather, it reflects a paring away of that which is inessential, beside the point. There is little time left. Why expend any of it on the sophistries of the world?

The Truisms

His father gave him a box of truisms

Shaped like a coffin, then his father died;

The truisms remained on the mantelpiece

As wooden as the playbox they had been packed in

Or that other his father skulked inside.

Then he left home, left the truisms behind him

Still on the mantelpiece, met love, met war,

Sordor, disappointment, defeat, betrayal,

Till through disbeliefs he arrived at a house

He could not remember seeing before.

And he walked straight in; it was where he had come from

And something told him the way to behave.

He raised his hand and blessed his home;

The truisms flew and perched on his shoulders

And a tall tree sprouted from his father's grave.

Louis MacNeice, Solstices (Faber and Faber 1961).

Charles Ginner (1878-1952), "Hartland Point from Boscastle" (1941)

The truisms mostly provide a framework for the world of humans, happenstance, and history, the world of fortune and of fate. As for the World -- the World of beautiful particulars -- that is something else entirely. I expect no explanations, answers, or solutions to arrive. That being said, I am always on the lookout for glimmers and glimpses, calls and whispers, from near or far. Yesterday, I came across thousands of tangled bare branches, a few passing white clouds, and a blue sky -- all floating on the surface of a puddle along the edge of a pathway. Birdsong was with me wherever I walked.

Still, there are truisms that apply both to the world and the World. For example: One thing leads to another. As I have noted here in the past, one of the charms of poetry is that you never know where a poem will take you. A few mornings ago, I read this:

Evening Rain by the Bridge

Showering, the rain by the bridge,

Under shadow, at nightfall is not yet hushed.

A fisherman in straw coat waits hesitant on the bluff;

The monks' gong sounds across the central stream.

Sad and still, bush clover at twilight --

Blue into the distance, water oats in autumn.

How beautiful is the clear shallow water!

Tranquil: a single sand gull.

Ichū Tsūjo (1349-1429) (translated by Marian Ury), in Marian Ury, Poems of the Five Mountains: An Introduction to the Literature of the Zen Monasteries (Center for Japanese Studies, University of Michigan 1992).

The poem is a kanshi: a poem written in Chinese characters by a Japanese poet. The writing of kanshi developed due to the popularity of classical Chinese poetry in Japan. A kanshi replicates the formal structures and prosodic features of Chinese poetry (the number of lines in a particular lyric form, the prescribed number of characters in each line, as well as requirements relating to rhyme, tonal patterns, and verbal parallelisms).

Although very few of the Japanese poets who wrote kanshi were fluent in, or spoke, Chinese, they were familiar with Chinese characters (known as kanji in Japanese) given that the characters are used in the Japanese writing system. For many years (particularly during the 14th and 15th centuries), the writing of kanshi was popular among Zen Buddhist monks due to Zen's origin in Chinese Ch'an Buddhism. A number of these monks had traveled to China to study Ch'an, and, while living there, had also grown fond of Chinese poetry.

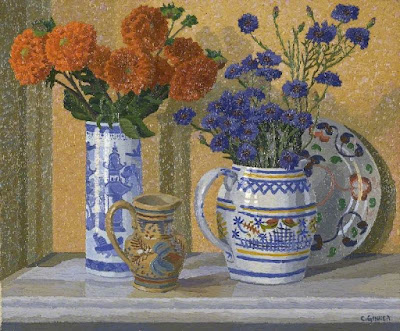

Charles Ginner, "Dahlias and Cornflowers" (1929)

Ichū Tsūjo's "Tranquil: a single sand gull" soon brought to mind one of Tu Fu's best-known, most-beloved poems:

A Traveler at Night Writes His Thoughts

Delicate grasses, faint wind on the bank;

stark mast, a lone night boat:

stars hang down, over broad fields sweeping;

the moon boils up, on the great river flowing.

Fame -- how can my writings win me that?

Office -- age and sickness have brought it to an end.

Fluttering, fluttering -- where is my likeness?

Sky and earth and one sandy gull.

Tu Fu (712-770) (translated by Burton Watson), in Burton Watson, The Columbia Book of Chinese Poetry: From Early Times to the Thirteenth Century (Columbia University Press 1984).

Very little has been written about Ichū Tsūjo in English, so I am not qualified to opine upon his familiarity either with Chinese poetry in general or with Tu Fu's poetry in particular. However, I suspect that he was familiar with both Tu Fu's poetry and with "A Traveler at Night Writes His Thoughts." I would also not be surprised if "Tranquil: a single sand gull" is a conscious echo of "Fluttering, fluttering -- where is my likeness?/Sky and earth and one sandy gull."

Charles Ginner, "Novar Cottage, Bearley, Warwickshire" (1933)

Tu Fu's "one sandy gull" in turn brought me to this, one of my favorite poems of spring:

The Chinese Restaurant in Portrush

Before the first visitor comes the spring

Softening the sharp air of the coast

In time for the first seasonal 'invasion.'

Today the place is as it might have been,

Gentle and almost hospitable. A girl

Strides past the Northern Counties Hotel,

Light-footed, swinging a book-bag,

And the doors that were shut all winter

Against the north wind and the sea-mist

Lie open to the street, where one

By one the gulls go window-shopping

And an old wolfhound dozes in the sun.

While I sit with my paper and prawn chow mein

Under a framed photograph of Hong Kong

The proprietor of the Chinese restaurant

Stands at the door as if the world were young,

Watching the first yacht hoist a sail

-- An ideogram on sea-cloud -- and the light

Of heaven upon the hills of Donegal;

And whistles a little tune, dreaming of home.

Derek Mahon, Collected Poems (The Gallery Press 1999).

Gulls. One thing leads to another: from the banks of a village stream in 14th century Japan, to a boat anchored in a great river in 8th century China, and, finally, to a seaside town in 20th century Northern Ireland. Are such journeys idle indulgences in a world of misery, calamity, and evil? Or are such journeys absolute necessities in a world of misery, calamity, and evil?

Charles Ginner, "Yellow Chrysanthemums" (1929)

In such days as these we must indeed take what refuge we can find. Much can be found in the Earth that "abides", as the book of Ecclesiastes says, and as the Japanese and Chinese poets you quote so often seemed to understand almost better than anyone. (In a fortunate conjunction, shortly before before the pandemic struck, I read George R. Stewart's fine novel, Earth Abides; its deep understanding - some would call it fatalism - about the smallness of who we are and the transitoriness of our achievements gave me a real resource for what lay ahead.)

ReplyDeleteRecently I've found such a refuge in the poetry of A.R. Ammons:

Mansion

So it came time

for me to cede myself

and I chose

the wind

to be delivered to

The wind was glad

and said it needed all

the body

it could get

to show its motions with

and wanted to know

willingly as I hoped it would

if it could do

something in return

to show its gratitude

When the tree of my bones

rises from the skin I said

come and whirlwinding

stroll my dust

around the plain

so I can see

how the ocotillo does

and how saguaro-wren is

and when you fall

with evening

fall with me here

where we can watch

the closing up of day

and think how morning breaks

Here there is no striving, no conflict or clamor or argument, no judgment, none of those shallow sentiments that so define our current moment. Instead, there is the peace, acceptance, and understanding that comes only from seeing deeply into the nature of things. Works like this are precious pieces of flotsam to carry us through the deluge, and more and more they are what I seek out to cling to.

Thank you as always fro providing us with new ones - we can never have too many.

The Truisms reminds me of G. K. Chesterton’s introduction to The Everlasting Man. “There are two ways of getting home; and one of them is to stay there. The other is to walk round the whole world till we come back to the same place....”

ReplyDeleteMr. Parker: Thank you very much for those lovely and eloquent thoughts. I share your feelings about the need for "refuge" in "such days as these." Your penultimate paragraph wonderfully articulates what these refuges can provide, and the place to which they point. I agree with your thought about the Japanese and Chinese poets whose works often appear here. They have provided refuges to me since I was young, but never more so than over the past two years. I think that the poem you share from A. R. Ammons has a great deal in common with their view of the world, as does your characterization of Stewart's understanding of the world, as expressed in his novel.

ReplyDeleteThank you again. It is always a pleasure to hear from you.

Esther: Thank you for sharing that. I haven't seen it before. It does fit quite well with "The Truisms," doesn't it?

ReplyDeleteWell, since we are talking about one thing leading to another, Chesterton's thought in turn brought this to mind (which I'm sure you know): "We shall not cease from exploration/And the end of all our exploring/Will be to arrive where we started/And know the place for the first time." (T. S. Eliot, "Little Gidding.")

As ever, thank you for visiting. It is nearly time for the cherry blossoms to arrive in your part of the world. I hope you will enjoy them. Take care.