Speaking of Derek Mahon, I recently realized that I have been remiss: it has been a few years since we last visited my favorite September poem.

September in Great Yarmouth

The woodwind whistles down the shore

Piping the stragglers home; the gulls

Snaffle and bolt their final mouthfuls.

Only the youngsters call for more.

Chimneys breathe and beaches empty,

Everyone queues for the inland cold --

Middle-aged parents growing old

And teenage kids becoming twenty.

Now the first few spots of rain

Spatter the sports page in the gutter.

Council workmen stab the litter.

You have sown and reaped; now sow again.

The band packs in, the banners drop,

The ice-cream stiffens in its cone.

The boatman lifts his megaphone:

'Come in, fifteen, your time is up.'

Derek Mahon, Poems, 1962-1978 (Oxford University Press 1979).

Reginald Brundrit (1883-1960), "The River" (c. 1924)

Late September, and the green leaves still outnumber those that have turned. As the boughs sway in a breeze, one hears a susurration, a sea-sound, not a rattling. On a clear day, leaf-shadows and patches of sunlight continue to revolve on the ground, kaleidoscopic, unceasing.

But yesterday afternoon I noticed dry yellow leaves gathering in the gutters as I walked through what was otherwise a green tunnel of trees. A group of three maples I have come to know as the earliest heralds of autumn began their transformation at the beginning of the month: the highest boughs and the leaves out at the tips of the lower branches are scarlet; only a dwindling inner core of summer green remains. "Now it is September and the web is woven./The web is woven and you have to wear it." (Wallace Stevens, "The Dwarf.")

The Crossing

September, and the butterflies are drifting

Across the sky again, the monarchs in

Their myriads, delicate lenses for the light

To fall through and be mandarin-transformed.

I guess they are flying southward, or anyhow

That seems to be the average of their drift,

Though what you mostly see is a random light

Meandering, a Brownian movement to the wind,

Which is one of Nature's ways of getting it done,

Whatever it may be, the rise of hills

And settling of seas, the fall of leaf

Across the shoulder of the northern world,

The snowflakes one by one that silt the field . . .

All that's preparing now behind the scene,

As the ecliptic and equator cross,

Through which the light butterflies are flying.

Howard Nemerov, Gnomes & Occasions (University of Chicago Press 1973).

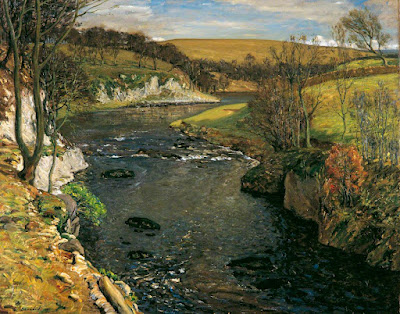

John Lawson (1868-1909), "An Ayrshire Stream" (1893)

I have a vague notion of what occurs when "the ecliptic and equator cross." Something to do with the movement of spheres, I suspect. But I'm reminded of my oft-repeated first principle of poetry: Explanation and explication are the death of poetry. Here is a wider principle I have adopted at this moment: Explanation and explication are the death of enchantment. The enchantment of the World, of course. Mind you, I accept the existence of the ecliptic and the equator. This is not an anti-scientific manifesto. I simply prefer, for instance, a single butterfly or a single leaf, with no explanations attached.

In a headnote to a haiku, Bashō (1644-1694) writes: "As we look calmly, we see everything is content with itself." (Bashō (translated by Makoto Ueda), in Makoto Ueda, Bashō and His Interpreters: Selected Hokku with Commentary (Stanford University Press 1991), page 153.) The haiku is: "Playing in the blossoms/a horsefly . . . don't eat it,/friendly sparrows!" (Bashō (translated by Makoto Ueda), Ibid, page 153.) Ueda provides this annotation: "The headnote is a sentence that often appears in Taoist classics, although Bashō probably took it from a poem by the Confucian philosopher Ch'eng Ming-tao." (Ibid, p. 153.)

Bashō's headnote brings to mind a notebook entry written by Samuel Taylor Coleridge: "September 1 -- the beards of Thistle & dandelions flying above the lonely mountains like life, & I saw them thro' the Trees skimming the lake like Swallows --." (Samuel Taylor Coleridge, in Kathleen Coburn (editor), The Notebooks of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Volume 1: 1794-1804 (Pantheon 1957), Notebook Entry 799 (September 1, 1800). The text is as it appears in the notebook.)

All of which leads us to a single leaf:

Threshold

When in still air and still in summertime

A leaf has had enough of this, it seems

To make up its mind to go; fine as a sage

Its drifting in detachment down the road.

Howard Nemerov, Gnomes & Occasions.

A single leaf. Or a single butterfly. No explanations required, or necessary.

A butterfly flits

All alone -- and on the field,

A shadow in the sunlight.

Bashō (translated by Makoto Ueda), in Makoto Ueda, Matsuo Bashō (Twayne 1970), page 50.

Henry Justice Ford (1860-1941)

"A View of Church Hill from the Mill Pond, Old Swanage" (1931)

[A coda. "The boatman" calling in someone out on the water whose "time is up" in Derek Mahon's "September in Great Yarmouth" makes an appearance in another poem:

Yorkshiremen in Pub Gardens

As they sit there, happily drinking,

their strokes, cancers, and so forth are not in their minds.

Indeed, what earthly good would thinking

about the future (which is Death) do? Each summer finds

beer in their hands in big pint glasses.

And so their leisure passes.

Perhaps the older ones allow some inkling

into their thoughts. Being hauled, as a kid, upstairs to bed

screaming for a teddy or a tinkling

musical box, against their will. Each Joe or Fred

wants longer with the life and lasses.

And so their time passes.

Second childhood; and 'Come in, number 80!'

shouts inexorably the man in charge of the boating pool.

When you're called you must go, matey,

so don't complain, keep it all calm and cool,

there's masses of time yet, masses, masses . . .

And so their life passes.

Gavin Ewart, in Philip Larkin (editor), Poetry Supplement Compiled by Philip Larkin for the Poetry Book Society (Poetry Book Society 1974). Ewart and Larkin were friends. The poem has a Larkinesque feel to it, doesn't it? It's not surprising that Larkin chose to include it in the Poetry Book Society's annual Christmas anthology.

But I like to think that if Larkin had written the poem he would have softened it a bit, and made beautifully clear that we are all Yorkshiremen in pub gardens, each in our own way. He likely would have done so in the final stanza: one long, lovely sentence hedged with one or two qualifications and perhaps containing a reversal -- but absolutely, humanly true. He is not the misanthropic, dour caricature he is often incorrectly made out to be by the inattentive. For example: "Something is pushing them/To the side of their own lives." (Philip Larkin, "Afternoons.") Or: "As they wend away/A voice is heard singing/Of Kitty, or Katy,/As if the name meant once/All love, all beauty." (Philip Larkin, "Dublinesque.") And this: "we should be careful//Of each other, we should be kind/While there is still time." (Philip Larkin, "The Mower.")

For some reason, I find myself reminded of a poem by Su Tung-p'o. It is a poem of spring, and thus may seem out of season. But the final line is apt in any season, and at any time, in any place.

Pear Blossoms by the Eastern Palisade

Pear blossoms pale white, willows deep green --

when willow fluff scatters, falling blossoms will fill the town.

Snowy boughs by the eastern palisade set me pondering --

in a lifetime how many springs do we see?

Su Tung-p'o (1036-1101) (translated by Burton Watson), in Burton Watson, Selected Poems of Su Tung-p'o (Copper Canyon Press 1994), page 68.

In a lifetime, how many Septembers do we see?]

Alexander Jamieson (1873-1937)

"Halton Lake, Wendover, Buckinghamshire"

We have much to learn from autumn leaves, which, as Jaccottet notes in Seedtime:

ReplyDelete'one by one detach themselves abruptly, at regular intervals, and fall silently, peacefully, enlarging the light. That which we are not capable of.'

(my translation)

Of the dozens of Septembers I have lived through, very few have I seen, or truly noticed. But every year, I notice more moments in such an intense way that they appear as individual miracles, like a butterfly or a leaf. September has insinuated itself into my consciousness in the last several years in such a way that it has become my favorite month, even in a year like this one, when it was not as summery as I like.

ReplyDeleteMahon's line about ice cream stiffening in its cone struck me hard. When I was at the market yesterday I tellingly did not buy any popsicles -- maybe that was a kind of stiffening.

I so appreciate your articulation of the problems of explaining everything. Heaven knows I read lots of explanations and discussions of everything under heaven. But more and more I have no explanations of my own -- only others' poetry to share -- and anyway, who can improve on what is said by the cosmos, if one has ears to hear it? You are right: Most of the time we can only muffle the voice of enchantment.

"Middle-aged parents growing old

ReplyDeleteAnd teenage kids becoming twenty."

I feel that.

I came over from Gretchen's blog. I'll be following you too now.

The metropolitan newspapers carried obituaries recently of Thomas Collins Jones, who wrote the book for musical The Fantastics, including the song "Try to Remember [The Kind of September]". As Guy Davenport wrote, "one of the things utterly forgotten about poets is that they come in hierarchies and orders." ("Do You Have a Poem Book on E.E. Cummings?", collected in The Geography of the Imagination.)

ReplyDeleteAcorns are falling here, and hickory nuts. Most of trees are still mostly green, though a scarlet oak out front has more brown leaves than it should have now.

Shri: Thank you for sharing the lovely passage from Philippe Jaccottet, which goes well here. Coincidentally, I included the same passage (as translated by Tess Lewis) in my October 23, 2016 post titled "Fallen." (Seven years ago already; the years do indeed fly by when you reach a certain age!)

ReplyDeleteSince you've reminded me, here are three additional passages from Jaccottet that I included in that same post. You may be familiar with them, but it's nice to share them again at this time of year. The first two are from Seedtime: Notebooks 1954-1979 (Seagull Books 2013), translated by Tess Lewis:

"The small yellow acacia leaves lie on the dark earth like immobile glimmers, mute, lighted mirrors." (Page 268.)

"Autumn trees: as if covered with yellow and white butterflies." (Page 268.)

The third passage is from Jaccottet's "Notes from the Ravine," which may be found in And, Nonetheless: Selected Prose and Poetry 1990-2009 (Chelsea Editions 2011), translated by John Taylor:

"This unexpected gift of a tree brightened by the low sun at the end of autumn, as when a candle is lit in a darkening room." (Page 343.)

Jaccottet is wonderful, whether writing about autumn, or any of the other seasons.

Thank you for visiting, and, again, for sharing the passage from Jaccottet.

Dear Mr Pentz

ReplyDeleteThank you for your reply, and for sharing those passages from Jaccottet. I was familiar with the first two (though it's always nice to read them again), but not with the last. It is beautiful. It reminds me of the lovely meditation about the cherry-tree from his 'Cahier de verdure' (I think the English version is called 'Green Notebook'), which you may be familiar with.

GretchenJoanna: Thank you very much for your lovely and thoughtful comments. And thank you as well for writing about, and linking to, the post on Gladsome Lights on September 27. That's very kind of you.

ReplyDeleteI completely agree with you about the importance of moments and of "individual miracles," and about the danger of too much explaining. Like you, I have also become more and more fond of September in recent years. Autumn has always been my favorite season, and October my favorite month, but September is gaining on October. Something about the cast of yellow light, and the mixture of green, blue, and gold. Who knows?

You are exactly right: "who can improve on what is said by the cosmos." And, oddly enough, reading poetry may eventually lead to the conclusion that the best way to live is to keep silent. (Of course, take this with a grain of salt coming from me, a lawyer by trade! I'm not likely to run out of words.)

As ever, thank you very much for your continuing presence here.

Sandi: That poem has many nice touches, doesn't it? September is quite evocative. As Mahon says in the line preceding the two lines you quote: "Everyone queues for the inland cold." I am old enough to remember my father playing Frank Sinatra's album September of My Years (released in 1965) on our "record player." The album included "It Was a Very Good Year" and "September Song." Songs like that will make an impression on you at an early age. "Come in, fifteen, your time is up."

ReplyDeleteI'm pleased you found your way here through Gladsome Lights. Thank you for visiting, and for sharing your thoughts. I hope you'll return.

George: It's good to hear from you again. I'm happy to know you are still stopping by.

ReplyDeleteThank you for reminding me of "Try to Remember": a song I had forgotten about. I'm old enough to have memories of hearing it on the radio. And thank you as well for the quote from Guy Davenport: very nice, and true. It prompted me to return to my copy of The Geography of the Imagination, and read the piece: a fine and humorous essay. I love the passing anecdote about reporters asking Ezra Pound questions after he was released from confinement: "he was detained momentarily by reporters asking the usual silly questions. 'Ovid had it a lot worse,' he said, and while they were looking at each other's notepads to see how to spell Ovid, he clapped his hat on his head, and walked off to take a ship to Italy."

I envy you the falling acorns and hickory nuts. Little of that out here. However, I do have fond memories of falling acorns, and of burning, smoldering piles of raked-up oak leaves on neighborhood lawns, from my childhood in Minnesota.

As always, thank you very much for visiting, and for sharing your thoughts.

Shri: Thank you for the follow-up comment, and for the reference to "Le cerisier." Mr. Taylor and Mark Treharne have made separate translations of the piece. Its opening paragraph provides, I think, a fine introduction to Jaccottet's view of the World, and to how he places himself within it. I have in mind in particular the phrase "luminous and convincing fragments of a joy" (Mr. Taylor's translation)/"luminous and genuine fragments of a sense of joy" (Mr. Treharne's translation). Of course, Jaccottet's writings are voluminous and varied, so I don't wish to oversimplify his work. However, the image of "glimmers," as you know, also appears in his works, and parallels "luminous and convincing fragments." Thus, a cherry tree, whatever the season.

ReplyDeleteThank you again.