One's Proper Place may be where one is right now. And where one is right now may be where one has been for ever. Although it may be hard to imagine in today's world, there was a time in which one lived and died where one was born. And this is still the case in many parts of the world. Perhaps this was not (and is not) such a bad thing.

Christopher Wood, "Lemons in a Blue Basket" (1922)

On One Who Lived and Died

Where He Was Born

When a night in November

Blew forth its bleared airs

An infant descended

His birth-chamber stairs

For the very first time,

At the still, midnight chime;

All unapprehended

His mission, his aim. --

Thus, first, one November,

An infant descended

The stairs.

On a night in November

Of weariful cares,

A frail aged figure

Ascended those stairs

For the very last time:

All gone his life's prime,

All vanished his vigour,

And fine, forceful frame:

Thus, last, one November

Ascended that figure

Upstairs.

On those nights in November --

Apart eighty years --

The babe and the bent one

Who traversed those stairs

From the early first time

To the last feeble climb --

That fresh and that spent one --

Were even the same:

Yea, who passed in November

As infant, as bent one,

Those stairs.

Wise child of November!

From birth to blanched hairs

Descending, ascending,

Wealth-wantless, those stairs;

Who saw quick in time

As a vain pantomime

Life's tending, its ending,

The worth of its fame.

Wise child of November,

Descending, ascending

Those stairs!

Thomas Hardy, Late Lyrics and Earlier, with Many Other Verses (1922).

Not surprisingly, the world-view of the "wise child of November" sounds a great deal like Hardy's own. This world-view is distilled in "He Never Expected Much" (written by Hardy when he was eighty-six), which begins:

Well, World, you have kept faith with me,

Kept faith with me;

Upon the whole you have proved to be

Much as you said you were.

Christopher Wood, "Angelfish, London Aquarium" (1930)

Saturday, March 31, 2012

Thursday, March 29, 2012

Memory: Variations On A Theme

Thomas Hardy claimed that he could clearly remember incidents that occurred 40 or 50 years earlier in his life. I have no reason to doubt his claim, particularly given the large number of poems that he wrote about scenes from his life, scenes in which the details -- both factual and emotional -- are quite specific. I suppose that this ability to remember was a blessing for Hardy's art, but a mixed blessing in terms of getting through an ordinary day: in some of his poems, the pain of recollection is palpable.

The following two poems address the oftentimes equivocal guises of memory.

In an Edinburgh Pub

An old fellow, hunched over a half pint

I hope he's remembering.

I hope he's not thinking.

Which comes first?

Memory, as always,

Lazarus of the past --

who comes sad or joyful,

but always carrying with him

a whiff of grave clothes.

Ewen McCaig, The Poems of Norman MacCaig (Polygon 2009). MacCaig wrote the poem in January of 1989, at the age of seventy-eight. This leads one to speculate who the "old fellow" in the poem might be (or at least who he might remind MacCaig of).

Charles Sheeler, "American Interior" (1932)

Emendations

"I fear this" should read: "as far away as."

"I remember" should read: "my memory fails me."

"I was aghast" should read: "I was, alas, distracted."

"The day was clear" should read: "the day is a blur."

In the penultimate sentence,

"I shall forever regret" should read: "I shall never regret"

Or, in the alternative: "my memory once again fails me."

The final sentence should be removed in its entirety.

sip (2011).

Charles Sheeler, "Spring Interior" (1927)

The following two poems address the oftentimes equivocal guises of memory.

In an Edinburgh Pub

An old fellow, hunched over a half pint

I hope he's remembering.

I hope he's not thinking.

Which comes first?

Memory, as always,

Lazarus of the past --

who comes sad or joyful,

but always carrying with him

a whiff of grave clothes.

Ewen McCaig, The Poems of Norman MacCaig (Polygon 2009). MacCaig wrote the poem in January of 1989, at the age of seventy-eight. This leads one to speculate who the "old fellow" in the poem might be (or at least who he might remind MacCaig of).

Emendations

"I fear this" should read: "as far away as."

"I remember" should read: "my memory fails me."

"I was aghast" should read: "I was, alas, distracted."

"The day was clear" should read: "the day is a blur."

In the penultimate sentence,

"I shall forever regret" should read: "I shall never regret"

Or, in the alternative: "my memory once again fails me."

The final sentence should be removed in its entirety.

sip (2011).

Tuesday, March 27, 2012

A Proper Place, Part One: "I Like It As It Is"

In a series of posts titled "No Escape" I have looked at the well-known phenomenon of "wherever you go, there you are." To wit: we imagine that everything in our life will fall magically into place if we can simply find the Ideal Place that, until now, has eluded us. It comes as no surprise that this is a delusion, a delusion that has been remarked upon by Montaigne, Johnson, and a host of others.

However, although the Ideal Place may be a chimera, a case may be made that a Proper Place can be found. I realize that this may seem like a distinction without a difference. But I see the distinction (somewhat fuzzily) as this: finding one's Proper Place does not guarantee "happiness" (whatever that is) or provide Big Answers (to allude to Elizabeth Jennings's poem "Answers"); however, a Proper Place may provide equanimity and content ("content" as in A. E. Housman's "that is the land of lost content/I see it shining plain").

The following poem by Neil Powell provides an example of what I am (inadequately) trying to articulate.

Charles Ginner, "Flask Walk, Skyline" (1934)

Covehithe

In my dream they said: "You must go to Covehithe."

I crossed over the causeway between two blue lakes

And I found myself on a long forest path

With a few wooden shacks and a glimpse of the sea.

I thought after all it was a place that might suit me.

But they said: "You must learn from your mistakes."

So, I have come to Covehithe. Low winter sun

Scans fields of pigs, dead skeletal trees,

Collapsing cliffs. There are ships on the horizon.

The great church, wrecked by civil war, not storm,

Now shields a smaller church from further harm.

And they were wrong: I like it as it is.

Neil Powell, The Times Literary Supplement, February 7, 2003.

Charles Ginner, "Lancaster from Castle Hill Terrace" (c. 1947)

However, although the Ideal Place may be a chimera, a case may be made that a Proper Place can be found. I realize that this may seem like a distinction without a difference. But I see the distinction (somewhat fuzzily) as this: finding one's Proper Place does not guarantee "happiness" (whatever that is) or provide Big Answers (to allude to Elizabeth Jennings's poem "Answers"); however, a Proper Place may provide equanimity and content ("content" as in A. E. Housman's "that is the land of lost content/I see it shining plain").

The following poem by Neil Powell provides an example of what I am (inadequately) trying to articulate.

Charles Ginner, "Flask Walk, Skyline" (1934)

Covehithe

In my dream they said: "You must go to Covehithe."

I crossed over the causeway between two blue lakes

And I found myself on a long forest path

With a few wooden shacks and a glimpse of the sea.

I thought after all it was a place that might suit me.

But they said: "You must learn from your mistakes."

So, I have come to Covehithe. Low winter sun

Scans fields of pigs, dead skeletal trees,

Collapsing cliffs. There are ships on the horizon.

The great church, wrecked by civil war, not storm,

Now shields a smaller church from further harm.

And they were wrong: I like it as it is.

Neil Powell, The Times Literary Supplement, February 7, 2003.

Charles Ginner, "Lancaster from Castle Hill Terrace" (c. 1947)

Sunday, March 25, 2012

"When Oats Were Reaped"

The delights of Thomas Hardy's poetry are inexhaustible. First, given that he wrote so many poems (the 1976 Macmillan edition of his complete poems contains 947), one is likely to encounter a previously unread poem when opening a volume of his poems at random. Second, one is also likely to discover something fresh when returning to a poem one knows. This may be due to having failed to pay sufficient attention the first time around, and/or to reading the poem after the passage of time, which may change the way you look at it.

I have read the following poem a few times over the years, but I fear that I let much of it pass me by in the past. On the surface, it may be viewed as a sly commentary on the proverbial phrase "sowing one's wild oats." To wit: we usually reap what we sow. It is just the sort of irony that Hardy was wont to fasten upon. But beneath the ostensibly simple surface a great deal of artifice is at work.

James McIntosh Patrick, "Stobo Kirk, Peeblesshire" (1936)

When Oats Were Reaped

That day when oats were reaped, and wheat was ripe, and barley ripening,

The road-dust hot, and the bleaching grasses dry,

I walked along and said,

While looking just ahead to where some silent people lie:

'I wounded one who's there, and now know well I wounded her;

But, ah, she does not know that she wounded me!'

And not an air stirred,

Nor a bill of any bird; and no response accorded she.

Thomas Hardy, Human Shows, Far Phantasies, Songs and Trifles (1925).

Of course, there is the sound. In line 1: "reaped . . . ripe . . . ripening." In line 5: "wounded one . . . well . . . wounded." The rhyming of "said" at the end of line 3 with "ahead" in the middle of line 4. And a repeat of that rhyming technique with "stirred" at the end of line 7 and "bird" in the middle of line 8.

Then there are the fine phrases. In line 4, Hardy refers to a place up ahead "where some silent people lie." Why did he not simply call it a "cemetery" or a "graveyard"? (Assuming that a rhyme could be found.) First, because, for Hardy (both in his life and in his art), the dead are never really dead, but are always with us. Second, because the silence of these people -- and of this person in particular -- is crucial to the poem: "no response accorded she."

I love the "ah" in line 6: "But, ah, she does not know that she wounded me!" Read the line without the "ah" and see if it makes a difference. I also like the ambiguity of the line (and, thus, of the poem as a whole). (Although perhaps it is just me being slow on the uptake that makes it seem ambiguous.) Is the speaker relieved that the dead woman never had to suffer guilt or grief for having wounded him, and now sleeps in peace? Or, is the speaker perturbed because the dead woman never had to suffer guilt or grief for having wounded him, and now sleeps in peace?

I have read the following poem a few times over the years, but I fear that I let much of it pass me by in the past. On the surface, it may be viewed as a sly commentary on the proverbial phrase "sowing one's wild oats." To wit: we usually reap what we sow. It is just the sort of irony that Hardy was wont to fasten upon. But beneath the ostensibly simple surface a great deal of artifice is at work.

James McIntosh Patrick, "Stobo Kirk, Peeblesshire" (1936)

When Oats Were Reaped

That day when oats were reaped, and wheat was ripe, and barley ripening,

The road-dust hot, and the bleaching grasses dry,

I walked along and said,

While looking just ahead to where some silent people lie:

'I wounded one who's there, and now know well I wounded her;

But, ah, she does not know that she wounded me!'

And not an air stirred,

Nor a bill of any bird; and no response accorded she.

Thomas Hardy, Human Shows, Far Phantasies, Songs and Trifles (1925).

Of course, there is the sound. In line 1: "reaped . . . ripe . . . ripening." In line 5: "wounded one . . . well . . . wounded." The rhyming of "said" at the end of line 3 with "ahead" in the middle of line 4. And a repeat of that rhyming technique with "stirred" at the end of line 7 and "bird" in the middle of line 8.

Then there are the fine phrases. In line 4, Hardy refers to a place up ahead "where some silent people lie." Why did he not simply call it a "cemetery" or a "graveyard"? (Assuming that a rhyme could be found.) First, because, for Hardy (both in his life and in his art), the dead are never really dead, but are always with us. Second, because the silence of these people -- and of this person in particular -- is crucial to the poem: "no response accorded she."

I love the "ah" in line 6: "But, ah, she does not know that she wounded me!" Read the line without the "ah" and see if it makes a difference. I also like the ambiguity of the line (and, thus, of the poem as a whole). (Although perhaps it is just me being slow on the uptake that makes it seem ambiguous.) Is the speaker relieved that the dead woman never had to suffer guilt or grief for having wounded him, and now sleeps in peace? Or, is the speaker perturbed because the dead woman never had to suffer guilt or grief for having wounded him, and now sleeps in peace?

James McIntosh Patrick, "Autumn, Kinnordy" (1936)

Friday, March 23, 2012

"Virtue"

There is something to be said for staying the course. (While being mindful that "everything passes and vanishes," as William Allingham writes.) Or does staying the course only seem admirable from without? Perhaps what is seen as faith and fortitude from the outside is resignation and habit from the inside. On the other hand, this line by Bob Dylan has haunted me for quite some time (since 1975, to be exact): "And old men with broken teeth stranded without love." ("Shelter from the Storm," Blood on the Tracks.)

The following poem by Bernard O'Donoghue is, along with Norman MacCaig's "Old Couple in a Bar," offered as a further commentary on (i.e., an attempt to escape from) Charlotte Mew's "frozen ghosts" of Brittany.

George Bellows, "The Lone Tenement" (1909)

Virtue

He had been unfaithful once, unlikely

as that seemed when, silver-haired and blind,

he let her lead him up the aisle each Sunday.

Some Jezebel, the story was, had lured him

off to Blackpool one weekend, long in the past.

I went along to Mass when I came home,

and enjoyed hearing the praise on every side

of such an exemplary grandnephew.

After he died, she moved to sheltered housing

somewhere near Parbold in the scenic north

of Lancashire, but we sometimes still went

to take her to Mass, tearfully sniffing

into her scented hankie, recalling George

and how she missed his arm upon her shoulder.

Bernard O'Donoghue, The Times Literary Supplement (November 19, 2004).

George Bellows, "Blue Morning" (1909)

The following poem by Bernard O'Donoghue is, along with Norman MacCaig's "Old Couple in a Bar," offered as a further commentary on (i.e., an attempt to escape from) Charlotte Mew's "frozen ghosts" of Brittany.

George Bellows, "The Lone Tenement" (1909)

Virtue

He had been unfaithful once, unlikely

as that seemed when, silver-haired and blind,

he let her lead him up the aisle each Sunday.

Some Jezebel, the story was, had lured him

off to Blackpool one weekend, long in the past.

I went along to Mass when I came home,

and enjoyed hearing the praise on every side

of such an exemplary grandnephew.

After he died, she moved to sheltered housing

somewhere near Parbold in the scenic north

of Lancashire, but we sometimes still went

to take her to Mass, tearfully sniffing

into her scented hankie, recalling George

and how she missed his arm upon her shoulder.

Bernard O'Donoghue, The Times Literary Supplement (November 19, 2004).

George Bellows, "Blue Morning" (1909)

Wednesday, March 21, 2012

"Old Couple In A Bar"

Charlotte Mew's vision of the old couple in Brittany as a pair of "frozen ghosts" is a bit discomfiting. Thus, an alternative view of love in old age is worth considering.

Old Couple in a Bar

They sit without speaking, looking straight ahead.

They've said it all before, they've seen it all before.

They're content.

They sit without moving: Ozymandias and Sphinx.

He says something! -- and she answers, smiling,

and taps him flirtatiously on the arm:

Daphnis and Chloe: with Edinburgh accents.

Ewen McCaig, The Poems of Norman MacCaig (Polygon 2009). MacCaig wrote the poem in December of 1980, at the age of 70.

Samuel Palmer, "Sheep in the Shade"

MacCaig performs a neat trick by moving from the "frown, and wrinkled lip" of the "shattered visage" of Shelley's Ozymandias to the pastoral love of Daphnis and Chloe on a timeless Greek island. A shepherdess and a shepherd ("with Edinburgh accents") sitting in a pub. Yes, this is indeed preferable to "frozen ghosts." (Although there is a time and a place for frozen ghosts as well. I would not wish to be without them entirely.)

Samuel Palmer, "Pastoral with a Horse-Chestnut Tree"

Old Couple in a Bar

They sit without speaking, looking straight ahead.

They've said it all before, they've seen it all before.

They're content.

They sit without moving: Ozymandias and Sphinx.

He says something! -- and she answers, smiling,

and taps him flirtatiously on the arm:

Daphnis and Chloe: with Edinburgh accents.

Ewen McCaig, The Poems of Norman MacCaig (Polygon 2009). MacCaig wrote the poem in December of 1980, at the age of 70.

Samuel Palmer, "Sheep in the Shade"

MacCaig performs a neat trick by moving from the "frown, and wrinkled lip" of the "shattered visage" of Shelley's Ozymandias to the pastoral love of Daphnis and Chloe on a timeless Greek island. A shepherdess and a shepherd ("with Edinburgh accents") sitting in a pub. Yes, this is indeed preferable to "frozen ghosts." (Although there is a time and a place for frozen ghosts as well. I would not wish to be without them entirely.)

Samuel Palmer, "Pastoral with a Horse-Chestnut Tree"

Monday, March 19, 2012

"Frozen Ghosts"

Some may disagree, but I think that Charlotte Mew and A. E. Housman do have something in common: their love poetry is nearly always about either unrequited love or love requited, but lost. The following poem by Mew seems to depart from the pattern. Still, I seem to detect a specter of future loss hovering at the edges. But perhaps I am being unfairly pessimistic. I would not wish to deprive Mew of any happiness she was able to find.

The Road to Kerity

Do you remember the two old people we passed on the road to Kerity,

Resting their sack, on the stones, by the drenched wayside,

Looking at us with their lightless eyes through the driving rain and then

out again

To the rocks and the long white line of the tide:

Frozen ghosts that were children once, husband and wife, father and

mother,

Looking at us with those frozen eyes --; have you ever seen anything quite

so chilled or so old?

But we -- with our arms about each other,

We did not feel the cold!

Charlotte Mew, The Farmer's Bride (1921). Kerity is a sea-side village in Brittany. Please note that lines 3, 5, and 6 are single lines, but the length limitations of this format do not permit them to appear as such.

James McIntosh Patrick, "City Garden" (1979)

The following poem is, alas, more in keeping with the way Mew's life turned out. But here is the proverbial rub: poetry is oftentimes born of sadness, isn't it?

I so liked Spring

I so liked Spring last year

Because you were here; --

The thrushes too --

Because it was these you so liked to hear --

I so liked you --

This year's a different thing, --

I'll not think of you --

But I'll like Spring because it is simply Spring

As the thrushes do.

Charlotte Mew, The Rambling Sailor (1929).

James McIntosh Patrick, "A City Garden" (1940)

The Road to Kerity

Do you remember the two old people we passed on the road to Kerity,

Resting their sack, on the stones, by the drenched wayside,

Looking at us with their lightless eyes through the driving rain and then

out again

To the rocks and the long white line of the tide:

Frozen ghosts that were children once, husband and wife, father and

mother,

Looking at us with those frozen eyes --; have you ever seen anything quite

so chilled or so old?

But we -- with our arms about each other,

We did not feel the cold!

Charlotte Mew, The Farmer's Bride (1921). Kerity is a sea-side village in Brittany. Please note that lines 3, 5, and 6 are single lines, but the length limitations of this format do not permit them to appear as such.

James McIntosh Patrick, "City Garden" (1979)

The following poem is, alas, more in keeping with the way Mew's life turned out. But here is the proverbial rub: poetry is oftentimes born of sadness, isn't it?

I so liked Spring

I so liked Spring last year

Because you were here; --

The thrushes too --

Because it was these you so liked to hear --

I so liked you --

This year's a different thing, --

I'll not think of you --

But I'll like Spring because it is simply Spring

As the thrushes do.

Charlotte Mew, The Rambling Sailor (1929).

James McIntosh Patrick, "A City Garden" (1940)

Saturday, March 17, 2012

Helpless

When I was a child I longed to be an adult. This longing was based upon two presumptions: first, that adults were free to do what they wanted to do (within the limits of law and morality, of course), and, second, that they knew exactly how to do these things (i.e., that they acted with complete self-assurance). I have since learned (speaking solely for myself) that those two presumptions were a bit optimistic.

The following poem by Frances Cornford (1886-1960) examines this state of affairs from a different angle, but it perhaps expresses part of what I am trying to get at.

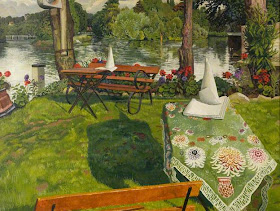

Stanley Spencer, "The Ferry Hotel Lawn, Cookham" (1936)

Childhood

I used to think that grown-up people chose

To have stiff backs and wrinkles round their nose,

And veins like small fat snakes on either hand,

On purpose to be grand.

Till through the banisters I watched one day

My great-aunt Etty's friend who was going away,

And how her onyx beads had come unstrung.

I saw her grope to find them as they rolled;

And then I knew that she was helplessly old,

As I was helplessly young.

Frances Cornford, Collected Poems (1954).

Gilbert Spencer, "The Terrace" (1927)

The following poem by Frances Cornford (1886-1960) examines this state of affairs from a different angle, but it perhaps expresses part of what I am trying to get at.

Stanley Spencer, "The Ferry Hotel Lawn, Cookham" (1936)

Childhood

I used to think that grown-up people chose

To have stiff backs and wrinkles round their nose,

And veins like small fat snakes on either hand,

On purpose to be grand.

Till through the banisters I watched one day

My great-aunt Etty's friend who was going away,

And how her onyx beads had come unstrung.

I saw her grope to find them as they rolled;

And then I knew that she was helplessly old,

As I was helplessly young.

Frances Cornford, Collected Poems (1954).

Gilbert Spencer, "The Terrace" (1927)

Thursday, March 15, 2012

"Landfall"

Randolph Stow (1935-2010) is best known as a novelist -- a novelist who fell silent during the last 26 years of his life. (However, he did occasionally review books for The Times Literary Supplement.) I have not read all of his novels, but I do recommend Visitants, The Girl Green as Elderflower, and The Suburbs of Hell (his final novel, published in 1984). Stow was born in Australia, but his later years were spent in Suffolk and Essex.

He also wrote poetry. As an alternative to Christina Rossetti's sleep, Philip Larkin's extinction, and Mary Coleridge's interstellar travel, Stow offers a vision of our fate that seems very peaceful (and -- thankfully -- quiet).

Richard Eurich, "Dorset Cove" (1939)

Landfall

And indeed I shall anchor, one day -- some summer morning

of sunflowers and bougainvillaea and arid wind --

and smoking a black cigar, one hand on the mast,

turn, and unlade my eyes of all their cargo;

and the parrot will speed from my shoulder, and white yachts glide

welcoming out from the shore on the turquoise tide.

And when they ask me where I have been, I shall say

I do not remember.

And when they ask me what I have seen, I shall say

I remember nothing.

And if they should ever tempt me to speak again,

I shall smile, and refrain.

Randolph Stow, A Counterfeit Silence: Selected Poems (Angus & Robertson 1969).

Richard Eurich, "Mousehole, Cornwall" (1938)

He also wrote poetry. As an alternative to Christina Rossetti's sleep, Philip Larkin's extinction, and Mary Coleridge's interstellar travel, Stow offers a vision of our fate that seems very peaceful (and -- thankfully -- quiet).

Richard Eurich, "Dorset Cove" (1939)

Landfall

And indeed I shall anchor, one day -- some summer morning

of sunflowers and bougainvillaea and arid wind --

and smoking a black cigar, one hand on the mast,

turn, and unlade my eyes of all their cargo;

and the parrot will speed from my shoulder, and white yachts glide

welcoming out from the shore on the turquoise tide.

And when they ask me where I have been, I shall say

I do not remember.

And when they ask me what I have seen, I shall say

I remember nothing.

And if they should ever tempt me to speak again,

I shall smile, and refrain.

Randolph Stow, A Counterfeit Silence: Selected Poems (Angus & Robertson 1969).

Richard Eurich, "Mousehole, Cornwall" (1938)

Tuesday, March 13, 2012

"Are The Dead As Calm As Those They Leave Behind Them?"

At the beginning of the month, I posted a poem by Christina Rossetti ("Life and Death") that contains the lines: "Life is not sweet. One day it will be sweet/To shut our eyes and die." Because of her religious faith, Rossetti was probably able to view this prospect with equanimity. Others (Philip Larkin, for instance) look upon death with horror since, for them, it means extinction:

. . . no sight, no sound,

No touch or taste or smell, nothing to think with,

Nothing to love or link with,

The anaesthetic from which none come round.

Philip Larkin, from "Aubade," Collected Poems (Faber and Faber 1988).

Jack Airy, "A House and Cottage near the Quay at Orford" (c. 1940)

In the following untitled poem, Mary Coleridge looks at things differently: she sees neither peaceful sleep nor horrific extinction ahead, but something else entirely. The prospect she offers is intriguing: interstellar travel. In any event, time will tell for each of us, won't it? (Not that we will be able to report back, of course.)

Are the dead as calm as those

They leave behind them, friends or foes?

However a man may love or fight

Calm he falls asleep at night!

Fast the living sleeps and well;

But the spirits -- who can tell?

Are they as a rushing flame

For the Sun from whence it came,

Driven on from star to star,

Where the other dead men are?

Theresa Whistler, The Collected Poems of Mary Coleridge (Rupert Hart-Davis 1954).

Jack Airy, "St Bartholomew's Church, Orford" (c. 1940)

. . . no sight, no sound,

No touch or taste or smell, nothing to think with,

Nothing to love or link with,

The anaesthetic from which none come round.

Philip Larkin, from "Aubade," Collected Poems (Faber and Faber 1988).

Jack Airy, "A House and Cottage near the Quay at Orford" (c. 1940)

In the following untitled poem, Mary Coleridge looks at things differently: she sees neither peaceful sleep nor horrific extinction ahead, but something else entirely. The prospect she offers is intriguing: interstellar travel. In any event, time will tell for each of us, won't it? (Not that we will be able to report back, of course.)

Are the dead as calm as those

They leave behind them, friends or foes?

However a man may love or fight

Calm he falls asleep at night!

Fast the living sleeps and well;

But the spirits -- who can tell?

Are they as a rushing flame

For the Sun from whence it came,

Driven on from star to star,

Where the other dead men are?

Theresa Whistler, The Collected Poems of Mary Coleridge (Rupert Hart-Davis 1954).

Jack Airy, "St Bartholomew's Church, Orford" (c. 1940)

Sunday, March 11, 2012

"Is The Noise I Hear From An Important Quarter?"

The quiet, self-contained life of a hedgehog seems romantically preferable to the noisy world in which we abide. As C. H. Sisson notes in the poem that appeared in my previous post: "The noise is more/Than ever it has been before." A great deal of this noise comes in the form of "news" (an extremely loose term in this day and age). The following poem by Sisson may serve as a further comment on the theme of "noise."

News

They live in the excitement of the news.

Who is what? What is that? And is the noise

I hear from an important quarter? When

Is what to happen? Who is what, finally?

Finally nobody is anything.

That is the end of it, my busy friend

And just as what you hear has no beginning

It has, assuredly, no certain end.

The end that comes is not the end of what,

The end of who perhaps, and perhaps not;

The rattle and the flashing lights are over,

Death is overt, but all the rest lies hidden.

Think of what you will, nothing will come of that,

What you intend is of all things the least;

As you spin on the lathe of circumstance

You are shaped, it is all the shape you have.

C. H. Sisson, Collected Poems (Carcanet 1998).

Kenneth Rowntree, "New Church, Llangelynnin" (1941)

Perhaps one of the secrets of freeing oneself from the news -- of becoming hedgehog-like -- is to come to the realization that there is no "important quarter" from which one can expect to hear news. There are no important quarters out there. All perspective has vanished, along with all credibility and decency. Mary Coleridge has the right idea.

No Newspapers

Where, to me, is the loss

Of the scenes they saw -- of the sounds they heard;

A butterfly flits across,

Or a bird;

The moss is growing on the wall,

I heard the leaf of the poppy fall.

Theresa Whistler (editor), The Collected Poems of Mary Coleridge (Rupert Hart-Davis 1954).

Mary Coleridge wrote "No Newspapers" in 1900, and thus had not yet encountered radio, television, and what not. Hence, perhaps we may silently consider "newspapers" to include a host of evils unknown to her.

Kenneth Rowntree, "Black Chapel, North End" (c. 1940)

News

They live in the excitement of the news.

Who is what? What is that? And is the noise

I hear from an important quarter? When

Is what to happen? Who is what, finally?

Finally nobody is anything.

That is the end of it, my busy friend

And just as what you hear has no beginning

It has, assuredly, no certain end.

The end that comes is not the end of what,

The end of who perhaps, and perhaps not;

The rattle and the flashing lights are over,

Death is overt, but all the rest lies hidden.

Think of what you will, nothing will come of that,

What you intend is of all things the least;

As you spin on the lathe of circumstance

You are shaped, it is all the shape you have.

C. H. Sisson, Collected Poems (Carcanet 1998).

Kenneth Rowntree, "New Church, Llangelynnin" (1941)

Perhaps one of the secrets of freeing oneself from the news -- of becoming hedgehog-like -- is to come to the realization that there is no "important quarter" from which one can expect to hear news. There are no important quarters out there. All perspective has vanished, along with all credibility and decency. Mary Coleridge has the right idea.

No Newspapers

Where, to me, is the loss

Of the scenes they saw -- of the sounds they heard;

A butterfly flits across,

Or a bird;

The moss is growing on the wall,

I heard the leaf of the poppy fall.

Theresa Whistler (editor), The Collected Poems of Mary Coleridge (Rupert Hart-Davis 1954).

Mary Coleridge wrote "No Newspapers" in 1900, and thus had not yet encountered radio, television, and what not. Hence, perhaps we may silently consider "newspapers" to include a host of evils unknown to her.

Kenneth Rowntree, "Black Chapel, North End" (c. 1940)

Friday, March 9, 2012

"The Noise Is More Than Ever It Has Been Before"

Periodically, I vow to tune out the babbling media world in which we live. (Hypocritically disregarding the fact that, as I type these words, I am, after a fashion (in a tiny way), participating in that world.) And, periodically, my vow is soon broken. Which does not stop me from (hypocritically) decrying this state of affairs.

The Trade

The language fades. The noise is more

Than ever it has been before,

But all the words grow pale and thin

For lack of sense has done them in.

What wonder, when it is for pay

Millions are spoken every day?

It is the number, not the sense

That brings the speakers pounds and pence.

The words are stretched across the air

Vast distances from here to there,

Or there to here: it does not matter

So long as there is media chatter.

Turn up the sound and let there be

No talking between you and me:

What passes now for human speech

Must come from somewhere out of reach.

C. H. Sisson, What and Who (1994).

Louisa Puller, "Haymill, Downton Gorge" (1941)

Near the end of the 19th century, Stephen Crane (1871-1900) wrote poetry that was bewildering and ahead of its time. The poems are untitled. It feels as though one has stumbled into the middle of a conversation or a story. What one hears may be portentous, or merely trivial. But the poetry is (for me, at least) oddly alluring (in small doses). Much of it seems prescient. Or, put another way, timeless.

Yes, I have a thousand tongues,

And nine and ninety-nine lie.

Though I strive to use the one,

It will make no melody at my will,

But is dead in my mouth.

Stephen Crane, The Black Riders and Other Lines (1895).

Louisa Puller, "The Railway Station at Tetbury" (1942)

The Trade

The language fades. The noise is more

Than ever it has been before,

But all the words grow pale and thin

For lack of sense has done them in.

What wonder, when it is for pay

Millions are spoken every day?

It is the number, not the sense

That brings the speakers pounds and pence.

The words are stretched across the air

Vast distances from here to there,

Or there to here: it does not matter

So long as there is media chatter.

Turn up the sound and let there be

No talking between you and me:

What passes now for human speech

Must come from somewhere out of reach.

C. H. Sisson, What and Who (1994).

Louisa Puller, "Haymill, Downton Gorge" (1941)

Near the end of the 19th century, Stephen Crane (1871-1900) wrote poetry that was bewildering and ahead of its time. The poems are untitled. It feels as though one has stumbled into the middle of a conversation or a story. What one hears may be portentous, or merely trivial. But the poetry is (for me, at least) oddly alluring (in small doses). Much of it seems prescient. Or, put another way, timeless.

Yes, I have a thousand tongues,

And nine and ninety-nine lie.

Though I strive to use the one,

It will make no melody at my will,

But is dead in my mouth.

Stephen Crane, The Black Riders and Other Lines (1895).

Louisa Puller, "The Railway Station at Tetbury" (1942)

Wednesday, March 7, 2012

"We Should Be Careful Of Each Other, We Should Be Kind While There Is Still Time"

The subject of hedgehogs brings to mind a lovely -- if sad -- poem by Philip Larkin. (Of course, "lovely -- if sad" perhaps describes the lion's share of his poems.) It is one of the few poems written by Larkin between the publication of High Windows in 1974 and his death in 1985.

John Nash, "Walled Pond, Little Bredy, Dorset" (1923)

The Mower

The mower stalled, twice; kneeling, I found

A hedgehog jammed up against the blades,

Killed. It had been in the long grass.

I had seen it before, and even fed it, once.

Now I had mauled its unobtrusive world

Unmendably. Burial was no help:

Next morning I got up and it did not.

The first day after a death, the new absence

Is always the same; we should be careful

Of each other, we should be kind

While there is still time.

Philip Larkin, Collected Poems (Faber and Faber 1988).

In a May 20, 1979, letter to his friend Judy Egerton, Larkin wrote: "At Easter I found a hedgehog cruising about my garden, clearly just woken up: it accepted milk, but went back to sleep I fancy, for I haven't seen it since." Anthony Thwaite (editor), Selected Letters of Philip Larkin, 1940-1985 (Faber and Faber 1992). On June 10 of the same year, Larkin wrote to Egerton: "This has been rather a depressing day: killed a hedgehog when mowing the lawn, by accident of course. It's upset me rather." Ibid. Larkin wrote "The Mower" on June 12.

Betty Mackereth, who worked with Larkin at the Brynmor Jones Library at the University of Hull, wrote the following comment about the poem:

"I remember too well Philip telling me of the death of the hedgehog: it was in his office the following morning with tears streaming down his face. The resultant poem ends with a message for everyone."

The Philip Larkin Society Website (May 2002).

John Nash, "Rocks and Water" (c. 1950)

John Nash, "Walled Pond, Little Bredy, Dorset" (1923)

The Mower

The mower stalled, twice; kneeling, I found

A hedgehog jammed up against the blades,

Killed. It had been in the long grass.

I had seen it before, and even fed it, once.

Now I had mauled its unobtrusive world

Unmendably. Burial was no help:

Next morning I got up and it did not.

The first day after a death, the new absence

Is always the same; we should be careful

Of each other, we should be kind

While there is still time.

Philip Larkin, Collected Poems (Faber and Faber 1988).

In a May 20, 1979, letter to his friend Judy Egerton, Larkin wrote: "At Easter I found a hedgehog cruising about my garden, clearly just woken up: it accepted milk, but went back to sleep I fancy, for I haven't seen it since." Anthony Thwaite (editor), Selected Letters of Philip Larkin, 1940-1985 (Faber and Faber 1992). On June 10 of the same year, Larkin wrote to Egerton: "This has been rather a depressing day: killed a hedgehog when mowing the lawn, by accident of course. It's upset me rather." Ibid. Larkin wrote "The Mower" on June 12.

Betty Mackereth, who worked with Larkin at the Brynmor Jones Library at the University of Hull, wrote the following comment about the poem:

"I remember too well Philip telling me of the death of the hedgehog: it was in his office the following morning with tears streaming down his face. The resultant poem ends with a message for everyone."

The Philip Larkin Society Website (May 2002).

John Nash, "Rocks and Water" (c. 1950)

Monday, March 5, 2012

Life Explained, Part Twenty-Five: "The Hedgehog"

A sweet-smelling garden at night. Beneath the stars, a hedgehog makes its rounds. Enough in themselves to provide a perfectly suitable Explanation of Life.

The Hedgehog

The garden is mysterious at night

And scented! and scented! in the night of stars.

The hedgehog snuffles somewhere among leaves,

Just by the arch-way. So it is with time

-- Mute night and then a voice that says nothing,

Busying itself, complaining and insisting:

When this has end, silence will come again.

C. H. Sisson, Collected Poems (Carcanet 1998).

Robin Tanner, "Wren and Primroses" (1935)

To think of Time as a hedgehog making its patient, imperturbable way through a garden, beneath a starry sky, is a fine image indeed, and is quite comforting.

"Those of us who have allowed our minds to be besotted by the pressure of personal affairs, who perhaps are wasting our time in amassing wealth that we can never hope to enjoy, might well have our folly corrected by an accidental glimpse of this self-contained individualist in his shirt of thorns moving out of the cavernous shadows of some cool odorous flower-bed.

Through the trembling leaves of the garden trees the summer stars shine bright on the outlandish back of the small quadruped, impressing the conscious intelligence with a clear comprehension of the wealth of earth-poetry revealed by the mere existence of so fabulous an urchin directing its activities by the light of the Milky Way."

Llewelyn Powys, "Hedgehogs."

Paul Drury, "March Morning" (1933)

The Hedgehog

The garden is mysterious at night

And scented! and scented! in the night of stars.

The hedgehog snuffles somewhere among leaves,

Just by the arch-way. So it is with time

-- Mute night and then a voice that says nothing,

Busying itself, complaining and insisting:

When this has end, silence will come again.

C. H. Sisson, Collected Poems (Carcanet 1998).

Robin Tanner, "Wren and Primroses" (1935)

To think of Time as a hedgehog making its patient, imperturbable way through a garden, beneath a starry sky, is a fine image indeed, and is quite comforting.

"Those of us who have allowed our minds to be besotted by the pressure of personal affairs, who perhaps are wasting our time in amassing wealth that we can never hope to enjoy, might well have our folly corrected by an accidental glimpse of this self-contained individualist in his shirt of thorns moving out of the cavernous shadows of some cool odorous flower-bed.

Through the trembling leaves of the garden trees the summer stars shine bright on the outlandish back of the small quadruped, impressing the conscious intelligence with a clear comprehension of the wealth of earth-poetry revealed by the mere existence of so fabulous an urchin directing its activities by the light of the Milky Way."

Llewelyn Powys, "Hedgehogs."

Paul Drury, "March Morning" (1933)

Saturday, March 3, 2012

"Good And Clever"

Perhaps I am growing old and grumpy, but it seems to me that the character trait that is most prized in today's world is "self-esteem." Of course, the flip side to "self-esteem" (unbeknownst to those who have it) is "self-delusion." Thus, for example, I suspect that there are a large number of us who feel that we are both good and clever. I offer the following poem by Elizabeth Wordsworth (1840-1932) as a possible source of humility. (And I do include myself among those who are in need of humility.)

Maxwell Armfield (1882-1972), "Still Life of Shells and Wrack" (1971)

Good and Clever

If all the good people were clever,

And all clever people were good,

The world would be nicer than ever

We thought that it possibly could.

But somehow 'tis seldom or never

The two hit it off as they should;

The good are so harsh to the clever,

The clever so rude to the good!

So, friends, let it be our endeavour

To make each by each understood,

For few can be good like the clever,

Or clever so well as the good!

Elizabeth Wordsworth, St. Christopher and Other Poems (1890).

Maxwell Armfield, "Seven Sisters" (1944)

Maxwell Armfield (1882-1972), "Still Life of Shells and Wrack" (1971)

Good and Clever

If all the good people were clever,

And all clever people were good,

The world would be nicer than ever

We thought that it possibly could.

But somehow 'tis seldom or never

The two hit it off as they should;

The good are so harsh to the clever,

The clever so rude to the good!

So, friends, let it be our endeavour

To make each by each understood,

For few can be good like the clever,

Or clever so well as the good!

Elizabeth Wordsworth, St. Christopher and Other Poems (1890).

Maxwell Armfield, "Seven Sisters" (1944)

Thursday, March 1, 2012

"One Day It Will Be Sweet To Shut Our Eyes . . ."

I try not to inflict my dreams on others. Thus, I beg your forbearance for what follows. I plead as an excuse that the dream is relevant only insofar as it relates to a poem by Christina Rossetti.

I recently had a dream of death. A nameless malady was afoot: it caused people to become drowsy; if they fell asleep, they died. I contracted the malady. I felt myself getting sleepy. I knew what would happen if I gave in to sleep. I was frightened. Yet, there was part of me that thought that giving in might not be such a bad thing: after all, it was only endless sleep that awaited me. The most vivid feature of the dream was the choice that I faced: to wit, the emotion involved in the pull between the fear of extinction and the release of just letting go.

Leonard Pike (1887-1959), "Going to the Circus" (c. 1940s)

A few days later, I thought of a poem by Christina Rossetti. It has been quite some time since I last read the poem (at least a year, I think), so it was not the source of the dream. I offer it, not as an explanation of the dream, but as a sort of counterpoint, or echo. (And, besides, the poem is far more interesting than the dream.)

Life and Death

Life is not sweet. One day it will be sweet

To shut our eyes and die:

Nor feel the wild flowers blow, nor birds dart by

With flitting butterfly,

Nor grass grow long above our heads and feet,

Nor hear the happy lark that soars sky high,

Nor sigh that spring is fleet and summer fleet,

Nor mark the waxing wheat,

Nor know who sits in our accustomed seat.

Life is not good. One day it will be good

To die, then live again;

To sleep meanwhile: so not to feel the wane

Of shrunk leaves dropping in the wood,

Nor hear the foamy lashing of the main,

Nor mark the blackened bean-fields, nor where stood

Rich ranks of golden grain

Only dead refuse stubble clothe the plain:

Asleep from risk, asleep from pain.

Christina Rossetti, The Prince's Progress and Other Poems (1866).

Leonard Pike, "The Chasing Shadows" (c. 1940s)

I recently had a dream of death. A nameless malady was afoot: it caused people to become drowsy; if they fell asleep, they died. I contracted the malady. I felt myself getting sleepy. I knew what would happen if I gave in to sleep. I was frightened. Yet, there was part of me that thought that giving in might not be such a bad thing: after all, it was only endless sleep that awaited me. The most vivid feature of the dream was the choice that I faced: to wit, the emotion involved in the pull between the fear of extinction and the release of just letting go.

Leonard Pike (1887-1959), "Going to the Circus" (c. 1940s)

A few days later, I thought of a poem by Christina Rossetti. It has been quite some time since I last read the poem (at least a year, I think), so it was not the source of the dream. I offer it, not as an explanation of the dream, but as a sort of counterpoint, or echo. (And, besides, the poem is far more interesting than the dream.)

Life and Death

Life is not sweet. One day it will be sweet

To shut our eyes and die:

Nor feel the wild flowers blow, nor birds dart by

With flitting butterfly,

Nor grass grow long above our heads and feet,

Nor hear the happy lark that soars sky high,

Nor sigh that spring is fleet and summer fleet,

Nor mark the waxing wheat,

Nor know who sits in our accustomed seat.

Life is not good. One day it will be good

To die, then live again;

To sleep meanwhile: so not to feel the wane

Of shrunk leaves dropping in the wood,

Nor hear the foamy lashing of the main,

Nor mark the blackened bean-fields, nor where stood

Rich ranks of golden grain

Only dead refuse stubble clothe the plain:

Asleep from risk, asleep from pain.

Christina Rossetti, The Prince's Progress and Other Poems (1866).

Leonard Pike, "The Chasing Shadows" (c. 1940s)