Bellow's assertion cuts both ways, doesn't it? Human nature harbors a boundless capacity for both good and evil. Who knows which of the two will appear next, and in what form? Caught up in the daily distraction (the latest political and media "crisis"), we are encouraged to bounce back and forth between hope and dread, anxiously awaiting "news." This is no way to live.

Nearly every day I walk past a small round meadow, about fifty feet wide, which is surrounded on all sides by tall pines. A single young maple stands near the center of the circle of grass and wildflowers. Each year I watch the maple change through the seasons, out there alone in the open. Who knows what will happen to it? It will likely outlive me, which is a comfort. We each go on in our own way.

Alternative worlds are available to us. Worlds free of flotsam and jetsam. I have recently been spending time with poems set to music in England in the late 16th and early 17th centuries. Another world (not without its own good and evil, of course), but one which feels seemlier and nobler than the one in which we now find ourselves. In the songs, one comes upon lines such as these:

Constant Penelope sends to thee, careless Ulysses.

Write not again, but come, sweet mate, thyself to revive me.

Troy we do much envy, we desolate lost ladies of Greece,

Not Priamus, nor yet all Troy can us recompense make.

Oh, that he had, when he first took shipping to Lacedaemon,

That adulter I mean, had been o'erwhelmed with waters.

Then had I not lain now all alone, thus quivering for cold,

Nor used this complaint, nor have thought the day to be so long.

Anonymous, in William Byrd, Psalms, Sonnets, and Songs of Sadness and Piety (1588), in E. H. Fellowes (editor), English Madrigal Verse 1588-1632 (Oxford University Press 1967), page 48. The eight lines are a translation of the opening lines of the First Epistle of Ovid's Heroides. Ibid, page 683.

What shall it be: Bedlam, or a world in which a poet forever unknown to us wrote of "constant Penelope"?

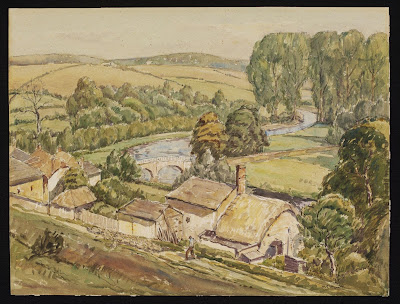

Robin Tanner (1904-1988), "The Gamekeeper's Cottage" (1928)

The Elizabethan era may indeed be a different world, but I was pleased to encounter these lines, which are timeless, in one of the songbooks:

The love of change hath changed the world throughout;

And what is counted good but that is strange?

New things wax old, old new, all turns about,

And all things change except the love of change.

Yet find I not that love of change in me,

But as I am so will I always be.

Anonymous, in Richard Carlton, Madrigals to Fine Voices (1601), Ibid, page 77. As is the case with many of the songs from the period, the identity of the poet is not known.

As one who is conservative in temperament (a temperament confirmed by six decades of watching the world), it is gratifying to discover a kindred soul from four centuries ago. The lamenters of change are always with us, aren't they? Mind you, the conservatism of which I speak has nothing whatsoever to do with contemporary politics, which are of no interest to me.

"Yet find I not that love of change in me" (a lovely line) in turn brings this to mind:

The Metropolitan Underground Railway

Here were a goodly place wherein to die; --

Grown latterly to sudden change averse,

All violent contrasts fain avoid would I

On passing from this world into a worse.

William Watson (1858-1935), Epigrams of Art, Life, and Nature (Gilbert Walmsley 1884).

I concede that the Underground is no doubt a marvelous thing. Having once lived in Tokyo, I recognize the convenience and efficiency of subways and train lines. But I sympathize with the sentiments expressed in the poem. "Grown latterly to sudden change averse." Yes. A time comes when one feels prepared to quietly and permanently exit the wearisome world of change.

Robin Tanner, "June" (1946)

But I feel I've lost the thread. The flotsam and jetsam of the modern world and aversion to change are ultimately of no moment. As always, one should attend to one's soul. Where does one start? Best to return to the solitary maple tree in the clearing among the pines. Everything begins and ends with a single beautiful particular.

A quiet bell sounds --

and reveals a village

waiting for the moon.

Sōgi (1421-1502) (translated by Steven Carter), in Steven Carter, The Road to Komatsubara: A Classical Reading of the Renga Hyakuin (Council on East Asian Studies, Harvard University 1987), page 96.

Robin Tanner, "Martin's Hovel" (1927)