And so it is again: a few days ago, as I idly made my way, I noticed buds at the tip of nearly every twig, each lit by the low sun, most still folded tight, others already unfolding. Before long, small white blossoms will appear. I was startled by this sudden green presence. Sleepwalking once again. But the World always finds a way to shake us awake.

A Thicket in Lleyn

I was no tree walking.

I was still. They ignored me,

the birds, the migrants

on their way south. They re-leafed

the trees, budding them

with their notes. They filtered through

the boughs like sunlight,

looked at me from three feet

off, their eyes blackberry bright,

not seeing me, not detaching me

from the withies, where I was

caged and they free.

They would have perched

on me, had I had nourishment

in my fissures. As it was,

they netted me in their shadows,

brushed me with sound, feathering the arrows

of their own bows, and were gone,

leaving me to reflect on the answer

to a question I had not asked.

"A repetition in time of the eternal

I AM." Say it. Don't be shy.

Escape from your mortal cage

in thought. Your migrations will never

be over. Between two truths

there is only the mind to fly with.

Navigate by such stars as are not

leaves falling from life's

deciduous tree, but spray from the fountain

of the imagination, endlessly

replenishing itself out of its own waters.

R. S. Thomas, Experimenting with an Amen (Macmillan 1986).

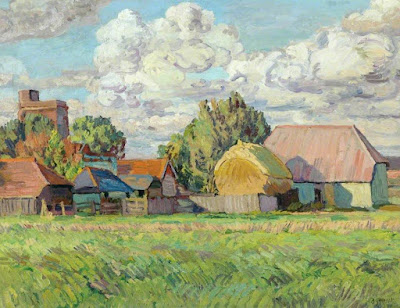

Duncan Grant (1885-1978), "Charleston Barn" (1942)

"A repetition in time of the eternal I AM" is a variation by Thomas on Coleridge's definition of "the primary Imagination": "The primary IMAGINATION I hold to be the living Power and prime Agent of all human Perception, and as a repetition in the finite mind of the eternal act of creation in the infinite I AM." (Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Biographia Literaria (1817) (edited by Adam Roberts) (Edinburgh University Press 2014), page 205.) Thomas' alteration of the language is interesting, for he seems to broaden the scope of Coleridge's conception: Coleridge is seeking to define the nature of "the Primary Imagination," but Thomas expands this into an observation on the nature of our existence.

However, I shouldn't get too carried away with this parsing of words, for I would never wish to sell Coleridge short when it comes to contemplations upon eternity or upon the eternal and infinite "I AM": they are arguably in the foreground and background of all his thought and work. For instance, one finds them again in the final sentence of Biographia Literaria:

"It is Night, sacred Night! the upraised Eye views only the starry Heaven which manifests itself alone: and the outward Beholding is fixed on the sparks twinkling in the aweful depth, though Suns of other Worlds, only to preserve the Soul steady and collected in its pure Act of inward Adoration to the great I AM, and to the filial WORD that re-affirmeth it from Eternity to Eternity, whose choral Echo is the Universe."

Ibid, page 414. ("Aweful" is an archaic spelling often used by Coleridge, particularly in his younger years. He uses it in this sense: "Solemnly impressive; sublimely majestic." (The Oxford English Dictionary, Second Edition (Clarendon Press 1989), page 833.) The spelling appears odd to modern eyes, but the presence of "awe" in the word is lovely. It's a shame that this sense of the word has been lost.)

With respect to Coleridge and "eternity," words written soon after Coleridge's death by Charles Lamb, his friend from childhood, are telling and touching:

"When I heard of the death of Coleridge, it was without grief. It seemed to me that he long had been on the confines of the next world, — that he had a hunger for eternity. I grieved then that I could not grieve. But, since, I feel how great a part he was of me. His great and dear spirit haunts me. I cannot think a thought, I cannot make a criticism on men and books, without an ineffectual turning and reference to him. He was the proof and touchstone of all my cognitions. . . . Never saw I his likeness, nor probably the world can see again."

Charles Lamb, in E. V. Lucas, The Life of Charles Lamb, Volume II (Methuen 1905), page 266. Coleridge died on July 25, 1834. Lamb's remarks were written in November of that year, "in the album of Mr. Keymer, a bookseller." Ibid. Lamb died soon after, on December 27.

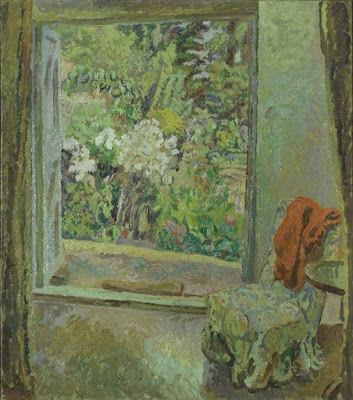

Duncan Grant, "The Doorway" (1929)

A recurring theme in the poetry of R. S. Thomas (one might even say the theme of his poetry) is the obdurate silence of God, and Thomas' impatience with, and ultimate acceptance of, that silence. The fact that Thomas was an Anglican priest certainly adds an interesting and deeper dimension to the situation.

At the same time, however, Thomas' preoccupation with this baffling, provocative, and powerful silence takes place in a World of immanence. And, at unexpected times and in unexpected places, all suddenly becomes clear: Something is there. As in "A Thicket in Lleyn." Or as in this:

Arrival

Not conscious

that you have been seeking

suddenly

you come upon it

the village in the Welsh hills

dust free

with no road out

but the one you came in by.

A bird chimes

from a green tree

the hour that is no hour

you know. The river dawdles

to hold a mirror for you

where you may see yourself

as you are, a traveller

with the moon's halo

above him, who has arrived

after long journeying where he

began, catching this

one truth by surprise

that there is everything to look forward to.

R. S. Thomas, Later Poems (Macmillan 1983).

Duncan Grant, "Laughton Castle" (c. 1930)

"He had a hunger for eternity." There are worse things to hunger after. And "there is everything to look forward to." All of this inevitably brings me to my favorite poem by Thomas, which has appeared here six times over the past eleven years. So please bear with me, dear readers: it needs to be here.

The Bright Field

I have seen the sun break through

to illuminate a small field

for a while, and gone my way

and forgotten it. But that was the pearl

of great price, the one field that had

the treasure in it. I realize now

that I must give all that I have

to possess it. Life is not hurrying

on to a receding future, nor hankering after

an imagined past. It is the turning

aside like Moses to the miracle

of the lit bush, to a brightness

that seemed as transitory as your youth

once, but is the eternity that awaits you.

R. S. Thomas, Laboratories of the Spirit (Macmillan 1975).

Duncan Grant, "Girl at the Piano" (1940)