Reading the poetry of Robert Herrick always helps to put our day-to-day world into perspective. For instance:

Nothing New

Nothing is new: we walk where others went.

There's no vice now, but has his precedent.

Robert Herrick, Hesperides (1648), in Tom Cain and Ruth Connolly (editors), The Complete Poetry of Robert Herrick, Volume I (Oxford University Press 2013), page 132.

The most recent editors of Hesperides suggest two possible sources for Herrick's poem. First, Ecclesiastes I.9-10: "The thing that hath been, it is that which shall be; and that which is done is that which shall be done: and there is no new thing under the sun. Is there any thing whereof it may be said, See, this is new? it hath been already of old time, which was before us." Second, Juvenal I.147-149: "Posterity will add nothing more to the ways we have, our descendants will do and desire the same things, all vice stands [always] at its high point." (Tom Cain and Ruth Connolly (editors), The Complete Poetry of Robert Herrick, Volume II (Oxford University Press 2013), page 627.)

Of course, the fact that there is nothing new under the sun provides cold comfort amidst the daily welter -- the horror and the folly -- of the news of the world. But perhaps we should at least add a line to Herrick's couplet in order to provide a semblance of balance. Something like this: "There's no virtue now, but has his precedent."

More importantly, beyond the dichotomy of vice and virtue, good and evil, there is -- at any and every moment -- something else, something further, something of another sort altogether.

On the Road on a Spring Day

There is no coming, there is no going.

From what quarter departed? Toward what quarter bound?

Pity him! in the midst of his journey, journeying --

Flowers and willows in spring profusion, everywhere fragrance.

Ryūsen Reisai (d. 1365) (translated by Marian Ury), in Marian Ury (editor), Poems of the Five Mountains: An Introduction to the Literature of the Zen Monasteries (Center for Japanese Studies, University of Michigan 1992), page 33.

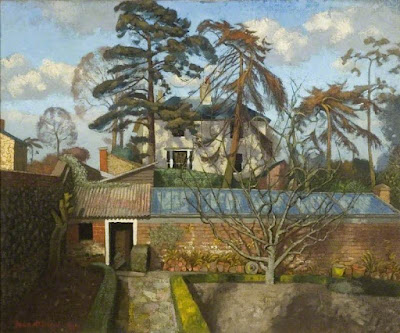

John Aldridge (1905-1983), "Roofing a New House"

This "something else" is where words come to an end. Yet still we persist. This is what human beings do.

"The old philosophy distinguished between knowledge achieved by effort (ratio) and knowledge received (intellectus) by the listening soul that can hear the essence of things and comes to understand the marvelous. But this calls for unusual strength of soul. The more so since society claims more and more and more of your inner self and infects you with its restlessness. It trains you in distraction, colonizes consciousness as fast as consciousness advances. The true poise, that of contemplation or imagination, sits right on the border of sleep and dreaming."

Saul Bellow, Humboldt's Gift (Viking 1975), page 306.

Bellow's passage is absolutely wonderful. Still, he is only reaffirming what has been said before, in many times and places and languages. And, for all his acuity, eloquence, good humor, and wisdom, we ultimately arrive at this (which, I acknowledge, raises questions about the value of what I am doing at this moment):

The more talking and thinking,

The farther from the truth.

Seng-ts'an (d. 606 A. D.) (translated by R. H. Blyth), in R. H. Blyth, Haiku, Volume 3: Summer-Autumn (Hokuseido Press 1952), page 68.

Seng-ts'an was the Third Patriarch of Ch'an Buddhism. The lines appear in a work by him titled Hsin Hsin Ming. Hsin Hsin Ming has been translated as (for example) "Faith in Mind," "On Trust in the Heart" (Arthur Waley), "Inscription on Trust in the Mind" (Burton Watson), and "Faith Mind Inscription." (Blyth identifies the source of the lines as "Shin Jin Mei," which is the Japanese transliteration of Hsin Hsin Ming. The Japanese transliteration of Seng-ts'an is "Sōsan.")

John Aldridge, "February Afternoon"

At some point, does one simply leave the welter behind, turn away, and keep quiet?

A Recluse

Here lies (where all at peace may be)

A lover of mere privacy.

Graces and gifts were his; now none

Will keep him from oblivion;

How well they served his hidden ends

Ask those who knew him best, his friends.

He is dead; but even among the quick

This world was never his candlestick.

He envied none; he was content

With self-inflicted banishment.

'Let your light shine!' was never his way:

What then remains but, Welladay!

And yet his very silence proved

How much he valued what he loved.

There peered from his hazed, hazel eyes

A self in solitude made wise;

As if within the heart may be

All the soul needs for company:

And, having that in safety there,

Finds its reflection everywhere.

Life's tempests must have waxed and waned:

The deep beneath at peace remained.

Full tides that silent well may be

Mark of no less profound a sea.

Age proved his blessing. It had given

The all that earth implies of heaven;

And found an old man reconciled

To die, as he had lived, a child.

Walter de la Mare, The Burning-Glass and Other Poems (Faber and Faber 1945).

For those of you, dear readers, who may not be acquainted with the poetry and prose of Walter de la Mare, I would suggest that the final two lines of "A Recluse" should not be taken as a criticism of the recluse. I would argue that, in de la Mare's world, the lines are arguably the highest form of praise (shot through with wistfulness and loss).

John Aldridge, "The Pant Valley, Summer, 1960"

In a deceptive way, it seems so very simple. It has all been said (and done -- rarely) before. But Bellow is right: "this calls for unusual strength of soul." I certainly cannot, and will never, claim to have that strength. As I have said here in the past, if one is lucky, and in the right place at the right time, one may catch glimpses, see glimmers.

A dreamy and elusive World it is. Like late August and early September: afternoon tree shadows lengthening each day across a bright meadow, new umber tints in green leaves, a thin thread of coolness in the wind, a slight but unmistakable change in the angle of the sunlight.

A butterfly flits

All alone -- and on the field,

A shadow in the sunlight.

Bashō (1644-1694) (translated by Makoto Ueda), in Makoto Ueda, Bashō (Kodansha 1982), page 50.

John Aldridge, "Beslyn's Pond, Great Bardfield"