Once again, dear readers, it is time to return to my favorite poem of April. Discovering a poem we love is a wonderful thing, but even more wonderful is the poem's continuing presence in our life over the years. We are not the same, the world is not the same, as when we last visited the poem. Who knows what awaits us when we arrive the next time?

Wet Evening in April

The birds sang in the wet trees

And as I listened to them it was a hundred years from now

And I was dead and someone else was listening to them.

But I was glad I had recorded for him the melancholy.

Patrick Kavanagh, Collected Poems (edited by Antoinette Quinn) (Penguin 2005). The poem was first published in Kavanagh's Weekly on April 19, 1952. Ibid, page 280.

No doubt I am a creature of habit, stuck in my settled ways. But "Wet Evening in April" never ceases to move me, whether I return to it in April as a ritual, or whether it unaccountably rises to the surface of its own accord, in any season, at any moment.

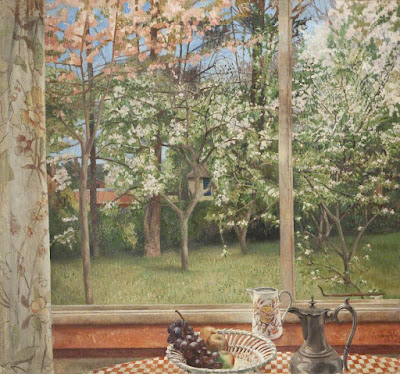

Richard Eurich (1903-1992), "The Window"

"But it is a sort of April weather life that we lead in this world. A little sunshine is generally the prelude to a storm." (William Cowper, letter to Walter Bagot (January 3, 1787), in James King and Charles Ryskamp (editors), The Letters and Prose Writings of William Cowper, Volume III: Letters 1787-1791 (Oxford University Press 1982), pages 5-6.) So it was in this part of the world yesterday afternoon, as I walked through alternating showers and sunlight, the waters of Puget Sound by turns dark gray and dazzling. So it is in the world at large.

Withal, there is an ever-present thread of beauty and truth running through our April weather life, through the April weather life of the world. Poetry is an instance of the existence of that thread.

Homage to Arthur Waley

Seattle weather: it has rained for weeks in this town,

The dampness breeding moths and a gray summer.

I sit in the smoky room reading your book again,

My eyes raw, hearing the trains steaming below me

In the wet yard, and I wonder if you are still alive.

Turning the worn pages, reading once more:

"By misty waters and rainy sands, while the yellow dusk thickens."

Weldon Kees, in The Collected Poems of Weldon Kees (edited by Donald Justice) (University of Nebraska Press 1975). The poem was first published in 1943.

As long time (and much appreciated!) readers of this blog may recall, Arthur Waley is one of my favorite translators of Chinese poetry into English (along with Burton Watson), and his translations have appeared here on many occasions. Thus, I was delighted when I first came across Kees' poem (most likely on a rainy day in Seattle).

The quotation from Waley in the final line is from Waley's translation of a four-line poem (chüeh-chü) by Po Chü-i:

A bend of the river brings into view two triumphal arches;

That is the gate in the western wall of the suburbs of Hsün-yang.

I have still to travel in my solitary boat three or four leagues --

By misty waters and rainy sands, while the yellow dusk thickens.

Po Chü-i (772-846) (translated by Arthur Waley), in Arthur Waley, One Hundred and Seventy Chinese Poems (Constable 1918). The poem is untitled. It appears in a two-poem sequence titled "Arriving at Hsün-yang." (By the way, Waley was in fact "still alive" when Kees wrote the poem: he died in 1966 at the age of 76.)

Richard Eurich, "The Rose" (1960)

Patrick Kavanagh meditates upon someone not yet born who will be listening to birds singing in wet trees in April a hundred years in the future, when Kavanagh will be long gone. By virtue of the art of Arthur Waley, Weldon Kees reads a poem written by Po Chü-i a thousand years ago in China. However fragile and contingent the world is, we mustn't forget this abiding thread.

To a Poet a Thousand Years Hence

I who am dead a thousand years,

And wrote this sweet archaic song,

Send you my words for messengers

The way I shall not pass along.

I care not if you bridge the seas,

Or ride secure the cruel sky,

Or build consummate palaces

Of metal or of masonry.

But have you wine and music still,

And statues and a bright-eyed love,

And foolish thoughts of good and ill,

And prayers to them who sit above?

How shall we conquer? Like a wind

That falls at eve our fancies blow,

And old Maeonides the blind

Said it three thousand years ago.

O friend unseen, unborn, unknown,

Student of our sweet English tongue,

Read out my words at night, alone:

I was a poet, I was young.

Since I can never see your face,

And never shake you by the hand,

I send my soul through time and space

To greet you. You will understand.

James Elroy Flecker, in John Squire (editor), The Collected Poems of James Elroy Flecker (Secker and Warburg 1947).

Richard Eurich, "The Road to Grassington" (1971)

.jpg)

20 comments:

I like Arthur Waley's translations, but when I read them I always wonder if I'm really reading an ancient Chinese poet or just Arthur Waley pretending to be an ancient Chinese poet.

Happy birthday month! (if I remember correctly).

Dear Stephen,

The threads continue as I read your poems and they lift my spirits and move me, and then I add them to my ceremonies and hopefully, they will be discovered again, years hence, in an old Order of Service and so the thread will spin onwards.

Thank you as always for your words and pictures,

With best wishes

Jane

James: Thank you for that thought. On the other hand, perhaps Waley's knowledge of the Chinese language and of Chinese poetry, philosophy, and culture, coupled with the fact that (in my humble opinion) he had a wonderful poetic sensibility and was a fine poet, means that he was not "pretending" at all. The only other translator of Chinese poetry who possesses these same characteristics is Burton Watson (again, in my humble opinion). (Which is not to say that I do not enjoy the work of other translators.)

As you likely know, if you read the comments by Waley and Watson about their respective approaches to translating Chinese poetry, you find that both of them were keenly aware of the importance of the poetic side (both technical and aesthetic) of their endeavors. One small example from Watson: "I myself translate into the spoken language of present-day America. It is obviously the language I know best and therefore the one in which, if I am to achieve any success at all, the chances for success seem brightest. That is, I proceed as though I were writing poetry of my own." (Watson, Chinese Lyricism (Columbia University Press 1971), page 14.) An example from Waley (more technical in nature): "Out of the Chinese five-word line I developed between 1916 and 1923 a metre, based on what Gerard Manley Hopkins called 'sprung rhythm,' which I believe to be just as much an English metre as blank verse." (Waley, Chinese Poems (George Allen and Unwin 1946), page 5.)

Of course, a great deal of scholarly ink has been spilled on the subject of the translation of poetry, including whether it is even possible. I also recognize that I am extremely protective of Waley who (together with Ezra Pound) introduced me to the beauty of Chinese poetry at a young and impressionable age, and to whom I am forever indebted, as the saying goes. Finally, reading over this, I realize that I may be sounding like a typical member of my profession: making a case for my client (and being long-winded at the same time) -- for which I apologize.

In any event, what matters in the end is the beauty and truth of Waley's translations, which enrich anyone who reads them. I'm sure we both agree on that. Again, thank you very much for your comment, and for visiting.

Esther: You have a good memory! April 11, to be exact. Thank you very much. Although, at this point in life, I hardly notice -- other than that the birthdays seem to come quicker and, alas, time seems to be speeding up. No help for that. Thank you again.

Jane: As always, it's good to hear from you. Thank you very much for the kind thoughts. I'm delighted to hear that some of the things that appear here may be spread further by you. That is exactly why I started doing this: to share the things I love in the hope that they may resonate with others as well. As you say, these threads will help to preserve the beauty of the poems (and paintings). One does what one can. I hope that all is well. Take care.

Arthur Waley also translated the ancient Genji Monogatari (The Tale of Genji), which was later translated anew by the formidable Edward Sidensticker. I once showed Sidensticker’s translation to a friend who was only familiar with Waley’s translation, and after just a few lines he said, disparagingly, “It’s not Waley’s English!” However, I attended a lecture by Edward Sidensticker here in Japan over forty years ago, in which he touched on the difference between his translation and Waley’s, and marveled at how much Waley had inserted into his text that “simply wasn’t there” in the original.

Along the same lines, Sidensticker also said was that it was “easy to improve on the original“ when translating, and harder to stick faithfully to the original text. Sidensticker’s translations were so known for their accuracy, that when another Japanese author’s work was translated into Norwegian (I believe), the Norwegian translator was accused by some of using Sidensticker’s English translation to translate from, instead of the original Japanese text. Sidensticker said he could discover when that was happening by putting “little mistakes” into his translation on purpose. :-)

Mr.Pentz

Permit me to add my good birthday wishes. May the year ahead be exactly what you most hope for. Your blog has brought poetry into my life in surprising and unlooked-for ways. I appreciate your quote from Arthur Waley relating the Chinese five-word line and Hopkins' sprung rhythm. This morning I was reading Hopkins 'The Wreck of the Deutschland'

Greetings from Scotland,Stephen.I have just discovered your blog and am looking forwad to exploring it in the future.

Following 'a thread of beauty and truth' from Cavanagh's 1952 poem, Wet Evening In April, I immediately linked it in my mind with a poem composed a dozen or so years previously,Never Again Would Bird's Song Be The Same, by Robert Frost. Both feature birdsong, loss and a sense of acute sadness.

Miss Emily (see below) walks among April's flowers and speaks to them as if they were children, and the flowers speak back to her as if they are children. We could say without dispute that, yes, Dickinson knew her Shakespeare, but what she knew best and what she adored, nurturing and tending and tenderly coaxing, were flowers. The night will come and the children will lie down in their beds, but when the April sun fills the sky with the red of dawn, the bumblebee will then awake the children. Oh me, I find "chubby daffodil" sprinkled with genius. Well, April is the thaumaturgist that strolls in with God's legerdemain, couldn't it be, sir?

Whose are the little beds, I asked

Which in the valleys lie?

Some shook their heads, and others smiled —

And no one made reply.

Perhaps they did not hear, I said,

I will inquire again —

Whose are the beds — the tiny beds

So thick upon the plain?

'Tis Daisy, in the shortest —

A little further on —

Nearest the door — to wake the Ist —

Little Leontoden.

'Tis Iris, Sir, and Aster —

Anemone, and Bell —

Bartsia, in the blanket red —

And chubby Daffodil.

Meanwhile, at many cradles

Her busy foot she plied —

Humming the quaintest lullaby

That ever rocked a child.

Hush! Epigea wakens!

The Crocus stirs her lids —

Rhodora's cheek is crimson,

She's dreaming of the woods!

Then turning from them reverent —

Their bedtime 'tis, she said —

The Bumble bees will wake them

When April woods are red.

Esther: Please accept my apologies for the delay in responding to your follow-up comments. Thank you for your interesting anecdotes and thoughts about translators and translations. I confess that, other than reading excerpts here and there, I have never braved the entirety of Genji Monogatari. How lucky you were to have encountered Seidensticker in Japan. If I ever get around to Genji, I suspect I will opt for his translation. Although, given my general fondness for Waley, I am wholly sympathetic with your friend's comment: "Waley's English" (as a translator or otherwise) is indeed wonderful. (He even wrote a few fine original poems in English, as you likely know. Some of them can be found in the tribute volume prepared for him in 1970: Madly Singing in the Mountains: An Appreciation and Anthology of Arthur Waley, edited by Ivan Morris.)

Translation is an interesting and troublesome subject, isn't it? I don't know what my life would be like without translations of Chinese and Japanese poetry, but I am aware that I am inevitably missing something. But so it is. One example. My introduction to -- and love of -- Chinese poetry began on the day I encountered Ezra Pound's translation of Li Po's "The River Merchant's Wife: A Letter" when I was in my second or third year of college. It's a cliché to say so, but my life changed on that day. "At fifteen I stopped scowling,/I desired my dust to be mingled with yours/Forever and forever and forever./Why should I climb the look-out? . . . The leaves fall early this autumn, in wind./The paired butterflies are already yellow with August/Over the grass in the West garden;/They hurt me. I grow older." On that day, I thought it was one of the most beautiful things I had ever encountered. I still feel the same way 45 or so years later, even though I eventually learned that Pound was wont to make mistakes, and take liberties, with respect to the original Chinese of the poems he translated.

Again, thank you very much for sharing your further thoughts.

Mr. Guirl: I apologize for the late response to your comment. Thank you very much for the birthday wishes. And thank you as well for the kind words about the blog. It has been a pleasure to have you here over the years.

That's a nice coincidence that Waley's comment came along when you were reading Hopkins. Reading Hopkins can be challenging, but once you spend enough time immersed in him, you begin to get into his flow. (Or, more properly, his rhythm!) At least that's what I find. I would have never connected Waley with Hopkins, so I found his comment enlightening when I came across it.

As ever, thank you very much for visiting. I hope that all is well.

Colm: Thank you very much for sharing Frost's poem as "a thread": it is lovely Another of those poems by him that take you aback, and make you shake your head in wonder, while not being completely sure what to make of it.

Here is yet another thread: I took out his Collected Poems to read the poem after receiving your comment, and I was delighted to discover that it immediately follows one of my favorite poems by him (or by anyone, for that matter): "The Most of It." Poetry and its threads are indeed wondrous. (And now you have sent me back to Frost, for which I am grateful.)

Thank you for your kind words about the blog, and for sharing the poem and your thoughts. I'm pleased you found your way here, and I hope you will return.

I have in front of me a beautiful book a friend gave me: "Translations From the Chinese" by Arthur Waley" (Illustrated by Cyrus LeRoy Baldridge.) It's open to "Arriving at Hsun-yang" (Two Poems) to the first one, the one you quote. It's on a big page, with an illustration -- yellow sky & water & a boat-- on the facing page,

I've been reading one poem from this book almost every day all year. It has helped me get through a fairly mild bout of Covid (vaccinated, boosted) & in general helped my spirits during a difficult time.

Another thing which has helped me has been your blog -- an oasis in what has been a dark winter & chilly early spring,

Susan

Bruce: Thank you very much for your sharing your thoughts, as well as Dickinson's poem. The flowers being asleep, awaiting April, is lovely. Due to my botanical ignorance, I had to search the internet for several of the flower names. (And discovered in the process, for instance, that "Leontoden" (or "leontodon") belongs to the dandelion family.) In doing so, I also ended up in some collections of Dickinson's flower poems, and discovered these beautiful lines (new to me, but not to you, I'm sure, with your deep knowledge of her poetry): "To be a Flower, is profound/Responsibility." What can one say about that? Silence is best.

Thank you very much for sharing so many wonderful poems by Dickinson (and others) over the years. To take up the "thread" theme again: my only purpose here is to keep these threads alive. I will always be grateful to you for adding to, and extending, the threads through the thoughts you have shared here, together with the poems you love. Thank you.

Susan: I'm so sorry to hear that you contracted COVID, but am relieved to hear that it was a "fairly mild" case. I hope you have fully recovered, or are well on the way to doing so.

What a nice coincidence that you have been reading Waley's translations. I'm sure his company -- and that of the Chinese poets (particularly wonderful and wise Po Chü-i, who Waley certainly felt a kinship with, having chosen to translate so many of his poems) -- was of solace, as well as a source of pleasure, during that time.

By the way, it sounds like we both have a copy of the book you speak of: I'm surmising that it is a large book bound in pumpkin-orange cloth hardcovers (with, as you say, illustrations), published by Knopf in 1941. It is indeed "a beautiful book." I was lucky enough to come across a copy while browsing in a used bookstore 40 or more years ago (when one depended on happenstance, not computers, to discover such treasures), and has been a valued companion since that time. It's nice to think of you enjoying the same volume.

Thank you very much for taking the time to visit, given the circumstances. I hope that all is now well, and that you will have a chance to get out and enjoy spring in some of your favorite places. Please take care.

Dear Mr Pentz,

Thank you very much for this fine anthology of poems. I think I commented on an earlier posting of the Flecker poem and mentioned Finzi‘s setting of it.

Gerald Finzi‘s wife Joy was an artist in her own right who counted Richard Eurich among others as a friend. So I was very touched when I noticed this subtle if unconscious bond of like minds in your post. Thank you again!

Yes, it is the same pumpkin-orange book (mine even has a black cardboard case). And Po Chu-i is indeed the best of companions. I have been reading his "Last Poem" over & over -- sometimes it seems as though it is happening in the next room.

Susan

Mr. Richter: You have an excellent memory! I checked the blog archives, and Flecker's poem appeared here in a post dated January 25, 2014, together with your comment on Finzi's setting, and your link to a performance of it. Thank you again. And thank you so much for your presence here for so many years!

I once again followed your earlier link to the performance, and I noticed that it appears on a CD titled "Gerald Finzi: A Song Outlasts a Dynasty." That title certainly resonates in light of the events in the world since February 24. I was intrigued about its source. A bit of internet research led me to a classical music blog which quoted something that Finzi wrote in October of 1938, after the signing of the Munich Agreement: "I should feel suicidal, if I didn't know a song outlasts a dynasty." Ah, well. (I suspect that you are no doubt already aware of Finzi's words, given your knowledge of him.)

That is a wonderful coincidence with respect to Joy Finzi and Richard Eurich. Little things like this (or perhaps they are not so "little," when all is said and done) are a comfort in days like these. Beauty and truth outlast a dynasty.

As always, I'm delighted to hear from you. I hope that all is well.

Susan: Thank you very much for your reply. I completely agree with you about "Last Poem": your thoughts about it are lovely and moving. One can only hope to have his equanimity. I have never ceased to marvel (for nearly five decades now) how I can feel such a strong connection (thanks to Arthur Waley) with a man who lived on the other side of the world twelve centuries ago.

I'm pleased we share this wonderful book in common. Thank you again for your follow-up thoughts.

Post a Comment