At Christmas, I turn to Thomas Hardy. (As well as to George Mackay Brown (for instance, "Christmas Poem": "We are folded all/In a green fable . . .") and R. S. Thomas (a bit astringent, as one might expect, but lovely; for instance, "Blind Noel": "Yet there is always room/on the heart for another/snowflake to reveal a pattern").) When it comes to Hardy, I invariably visit this:

The Oxen

Christmas Eve, and twelve of the clock.

"Now they are all on their knees,"

An elder said as we sat in a flock

By the embers in hearthside ease.

We pictured the meek mild creatures where

They dwelt in their strawy pen,

Nor did it occur to one of us there

To doubt they were kneeling then.

So fair a fancy few would weave

In these years! Yet, I feel,

If someone said on Christmas Eve,

"Come; see the oxen kneel

"In the lonely barton by yonder coomb

Our childhood used to know,"

I should go with him in the gloom,

Hoping it might be so.

Thomas Hardy, Moments of Vision and Miscellaneous Verses (Macmillan 1917). A "barton" is a farmyard. The poem was first published in The Times on December 24, 1915. (J. O. Bailey, The Poetry of Thomas Hardy: A Handbook and Commentary (University of North Carolina Press 1970), page 370.)

At some point in his life, Hardy lost his faith. But he wrote "The Oxen" without irony. This may be difficult for most irony-afflicted moderns to believe (in the unlikely event they should ever come across the poem). But I take Hardy at his word. And I would do as he says he would do.

Edmund Blunden writes this of "The Oxen":

"Like so many of his poems, this one sprang from lonely musing on scenes of the past and their application to the present. . . . The picture is one to delight us still in troubled times. A quiet Christmas Eve almost a hundred years ago, in a Dorset cottage, by firelight, and an old man, unaware of anything remarkable in his talk, says that the cattle in the shed are on their knees now. Everyone agrees silently. A boy looks especially attentive. The years run by, and there is the attentive boy Hardy himself grown an old man, realizing the universal appeal in that local superstition, the reviving life in it."

Edmund Blunden, Thomas Hardy (Macmillan 1941), page 153.

Blunden was a friend of Hardy's, and was quite fond of him. One senses respect, but also a bit of skepticism, in his discussion of "The Oxen." Given Blunden's experiences in the trenches during the First World War, and the date on which the poem was published, this is understandable. But, again, I take Hardy on his word.

"Reason is great, but it is not everything. There are in the world things not of reason, but both below and above it; causes of emotion, which we cannot express, which we tend to worship, which we feel, perhaps, to be the precious elements in life." (Gilbert Murray, A History of Ancient Greek Literature (Heinemann 1897), page 272.)

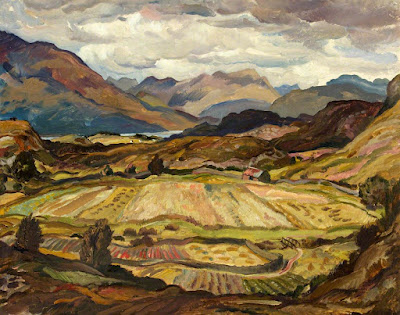

Ben Nicholson (1894-1982), "1930 (Christmas Night)" (1930)

In writing of his admiration for Hardy's poetry, Thom Gunn notes that, in reading the poetry, he has a "feeling of contact with an honest man who will never lie to me." (Thom Gunn, "Hardy and the Ballads," in The Occasions of Poetry: Essays in Criticism and Autobiography (North Point Press 1985), page 105.) Kingsley Amis says something uncannily similar about Edward Thomas: "How a poet convinces you he will not tell you anything he does not think or feel, since you have only his word for it, is hard to discover, but Edward Thomas is one of those who do it." (Kingsley Amis, The Amis Anthology (Arena 1989), page 339.) I completely agree with what Amis says of Edward Thomas, and I believe it is true of Thomas Hardy as well.

These comments about poetic honesty are complemented quite well by this fine observation about Hardy and his poetry by F. L. Lucas: "He deliberately took for his subjects the commonest and most natural feelings; but by an unfamiliar side, and with that insight which only sensitiveness and sympathy can possess. This sympathy is important; for, as I have said, if truthfulness is one main feature of Hardy's work, its compassion is another." (F. L. Lucas, Ten Victorian Poets (Cambridge University Press 1940), page 192.)

All of this leads us in a roundabout way back to Hardy's Christmas poetry, which is where we ought to be:

Christmastide

The rain-shafts splintered on me

As despondently I strode;

The twilight gloomed upon me

And bleared the blank high-road.

Each bush gave forth, when blown on

By gusts in shower and shower,

A sigh, as it were sown on

In handfuls by a sower.

A cheerful voice called, nigh me,

"A merry Christmas, friend!" --

There rose a figure by me,

Walking with townward trend,

A sodden tramp's, who, breaking

Into thin song, bore straight

Ahead, direction taking

Toward the Casuals' gate.

Thomas Hardy, Winter Words in Various Moods and Metres (Macmillan 1928). "The Casuals' gate" refers to a gate at the Union House, a workhouse in Dorchester, Dorset. (J. O. Bailey, The Poetry of Thomas Hardy: A Handbook and Commentary, page 581.) "In Hardy's time any 'casual' (pauper or tramp) could apply to the police for a ticket, with which he would be admitted for supper, a bed, and breakfast." (Ibid.)

With that (and with a grateful thank you to Thomas Hardy): "A merry Christmas, friend!"

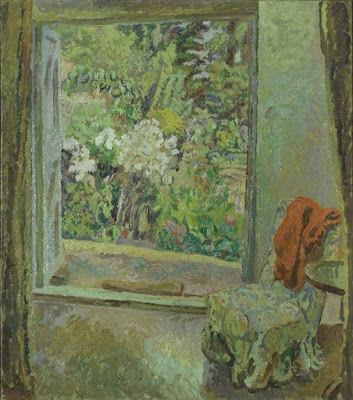

Robin Tanner (1904-1988) "Christmas" (1929)