Last week I took an afternoon walk on a warm, breezy, cloudless day. At times I paused beneath the trees, looking upward, listening to the leaves. A thought suddenly occurred to me: it is enough to have been put into this World simply to see blue sky beyond swaying boughs of green leaves on a summer afternoon. At last, there is nothing to be said, no thoughts worth thinking.

The River of Rivers in Connecticut

There is a great river this side of Stygia,

Before one comes to the first black cataracts

And trees that lack the intelligence of trees.

In that river, far this side of Stygia,

The mere flowing of the water is a gayety,

Flashing and flashing in the sun. On its banks,

No shadow walks. The river is fateful,

Like the last one. But there is no ferryman.

He could not bend against its propelling force.

It is not to be seen beneath the appearances

That tell of it. The steeple at Farmington

Stands glistening and Haddam shines and sways.

It is the third commonness with light and air,

A curriculum, a vigor, a local abstraction . . .

Call it, once more, a river, an unnamed flowing,

Space-filled, reflecting the seasons, the folk-lore

Of each of the senses; call it, again and again,

The river that flows nowhere, like a sea.

Wallace Stevens, The Collected Poems (Alfred A. Knopf 1954), page 533.

The Collected Poems, Stevens' final volume of poetry, was published on October 1, 1954, the day before he turned seventy-five. "The River of Rivers in Connecticut" is the penultimate poem in the book. It appears in a section titled The Rock, which contains the poems Stevens wrote after the publication of The Auroras of Autumn in 1950. Stevens died on August 2, 1955.

I have been visiting Stevens' poetry recently, and at the same time I have been reading poetry written by Sōchō (1448-1532). Sōchō's poems appear in a journal kept by him from 1522 to 1527, when he was in his seventies. He was a renga (linked-verse) master, and spent much of his life traveling throughout Japan, participating in renga sessions, during a tumultuous and violent time. Many of the poems in the journal are hokku, the three-line verse form which constitutes the opening link in a renga. Hokku evolved into the free-standing poem we now know as haiku.

Yet gently blows the wind,

and gently fall the leaves

from the willow trees!

Sōchō (translated by H. Mack Horton), in H. Mack Horton (editor and translator), The Journal of Sōchō (Stanford University Press 2002), page 109.

By happenstance, I have discovered that Sōchō's poems and Stevens' late poems in The Rock go together well. I am loath to depart from the two septuagenarians. They are fine companions.

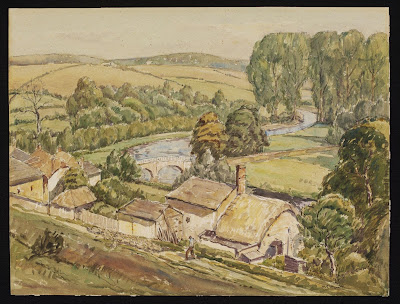

Paul Nash (1889-1946), "Berkshire Downs" (1922)

The evidence suggests that Stevens devoted a great deal of time to the arrangement of the poems that appear in The Rock. He selected this as the opening poem:

An Old Man Asleep

The two worlds are asleep, are sleeping, now.

A dumb sense possesses them in a kind of solemnity.

The self and the earth -- your thoughts, your feelings,

Your beliefs and disbeliefs, your whole peculiar plot;

The redness of your reddish chestnut trees,

The river motion, the drowsy motion of the river R.

Wallace Stevens, The Collected Poems, page 501.

I am reluctant to venture beyond the words of Stevens' poems. Far too much ink has already been spilled by the Wallace Stevens academic-industrial complex. What could I possibly add? Alas, how can I resist? First, "An Old Man Asleep" is lovely, which is all that matters. The words and their sound. Second, "the two worlds" ("the self and the earth") are something to bear in mind when reading any poem by Stevens. Third, and wonderfully, a beautiful particular: "The river motion, the drowsy motion of the river R." Again, best to leave beauty as it is, and the words as they are, without comment. Yet one should be aware of the lovely and important place that rivers occupy in Stevens' poetry. "The River of Rivers in Connecticut" is probably my favorite Stevens poem, but it has close competitors, one of which is "

This Solitude of Cataracts": "He never felt twice the same about the flecked river,/Which kept flowing and never the same way twice . . ."

With respect to "the drowsy motion of the river R" -- "an unnamed flowing" -- and its "gayety," "propelling force," and fatefulness, this may be worth considering:

"At all times some things are hastening to come into being, and others to be no more; and of that which is coming to be, some part is already extinct. Flux and transformation are forever renewing the world, as the ever-flowing stream of time makes boundless eternity forever young. So in this torrent, in which one can find no place to stand, which of the things that go rushing past should one value at any great price? It is as though one began to lose one's heart to a little sparrow flitting by, and no sooner has one done so than it has vanished from sight."

Marcus Aurelius (translated by Robin Hard), Meditations, Book VI, Section 15 (Oxford University Press 2011), page 48.

That's enough of that. A few words from Sōchō are in order:

A morning glory --

like dreams or dew, the flower

blooms but a moment.

Sōchō (translated by H. Mack Horton), in H. Mack Horton (editor and translator), The Journal of Sōchō, page 108.

Paul Nash, "Behind the Inn" (1922)

"It is enough to have been put into this World simply to see blue sky beyond swaying boughs of green leaves on a summer afternoon." So it seemed to me for a moment as I stood beneath a tree last week. Ah, merely a passing fancy. A hasty, ill-considered conclusion. Pretentious and overly-dramatic as well. There is much more to life than blue sky and green leaves, isn't there?

A few days later, something written by Walter Pater came to mind: "He has been a sick man all his life. He was always a seeker after something in the world that is there in no satisfying measure, or not at all." (Walter Pater, "A Prince of Court Painters," in Imaginary Portraits (Macmillan 1887), page 48.) But of course.

And yet there is the final poem in The Rock, which is also the final poem in The Collected Poems. As is the case with "The River of Rivers in Connecticut" (which immediately precedes it) and "An Old Man Asleep," Stevens placed it where it is with intent.

Not Ideas about the Thing but the Thing Itself

At the earliest ending of winter,

In March, a scrawny cry from outside

Seemed like a sound in his mind.

He knew that he heard it,

A bird's cry, at daylight or before,

In the early March wind.

The sun was rising at six,

No longer a battered panache above snow . . .

It would have been outside.

It was not from the vast ventriloquism

Of sleep's faded papier-mâché . . .

The sun was coming from outside.

That scrawny cry -- it was

A chorister whose c preceded the choir.

It was part of the colossal sun,

Surrounded by its choral rings,

Still far away. It was like

A new knowledge of reality.

Wallace Stevens, The Collected Poems, page 534.

This time I will stay silent, and defer to Sōchō:

In the moon's clear light

all mundane desires

are but a path of dreams.

Sōchō (translated by H. Mack Horton), in H. Mack Horton (editor and translator), The Journal of Sōchō, page 29.

Paul Nash, "Oxenbridge Pond" (1928)