For Once, Then, Something

Others taunt me with having knelt at well-curbs

Always wrong to the light, so never seeing

Deeper down in the well than where the water

Gives me back in a shining surface picture

Me myself in the summer heaven godlike

Looking out of a wreath of fern and cloud puffs.

Once, when trying with chin against a well-curb,

I discerned, as I thought, beyond the picture,

Through the picture, a something white, uncertain,

Something more of the depths -- and then I lost it.

Water came to rebuke the too clear water.

One drop fell from a fern, and lo, a ripple

Shook whatever it was lay there at bottom,

Blurred it, blotted it out. What was that whiteness?

Truth? A pebble of quartz? For once, then, something.

Robert Frost, New Hampshire (Henry Holt 1923) (italics in original text).

"Me myself in the summer heaven godlike/Looking out of a wreath of fern and cloud puffs." Narcissus is implied here, I would presume. Frost has it right, doesn't he? And he doesn't spare himself from the recognition. There is indeed something out there in the World, but we are often ill-suited to engage in the search for it. I can personally (and ruefully) attest to that. All of this internal and external noise and gesticulation and distraction, signifying nothing.

Of course, one must take what Frost says in his poems with a grain of salt. He was, after all, a master of qualifications, reversals, and qualified reversals. (As was his dear friend Edward Thomas.) What does "For Once, Then, Something" really mean? Long-time (and much-appreciated!) readers of this blog may recall one of my two fundamental poetic principles: Explanation and explication are the death of poetry. (For those who may be interested, the other principle is: It is the individual poem that matters, not the poet.) Hence, I will leave the poem alone.

But, despite my principles, I do forage around in "literary criticism" now and then. In doing so, I discovered an article about a poetry reading that Frost gave at Harvard on October 16, 1962. "For Once, Then, Something" was one of the poems he read that day. After reciting it, Frost said: "Well, that's one of the humblest poems I ever wrote." (Robert W. Hill, Jr., "Robert Frost: A Personal Reminiscence," The Robert Frost Review, Number 8 (Fall 1998), page 13.) Something to consider.

"Attachment to the self renders life more opaque. One moment of complete forgetting and all the screens, one behind the other, become transparent so that you can perceive clarity to its very depths, as far as the eye can see; and at the same time everything becomes weightless. Thus does the soul truly become a bird."

Philippe Jaccottet (translated by Tess Lewis), in Philippe Jaccottet, Seedtime: Notebooks, 1954-1979 (Seagull Books 2013), page 1.

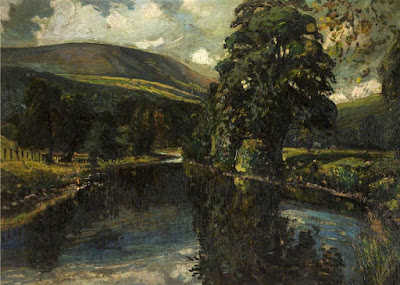

Alexander Jamieson (1873-1937), "Doldowlod on the Wye" (1935)

Best to keep still, silent, and attentive. You never know what may arrive, and when.

The Most of It

He thought he kept the universe alone;

For all the voice in answer he could wake

Was but the mocking echo of his own

From some tree-hidden cliff across the lake.

Some morning from the boulder-broken beach

He would cry out on life, that what it wants

Is not its own love back in copy speech,

But counter-love, original response.

And nothing ever came of what he cried

Unless it was the embodiment that crashed

In the cliff's talus on the other side,

And then in the far distant water splashed,

But after a time allowed for it to swim,

Instead of proving human when it neared

And someone else additional to him,

As a great buck it powerfully appeared,

Pushing the crumpled water up ahead,

And landed pouring like a waterfall,

And stumbled through the rocks with horny tread,

And forced the underbrush — and that was all.

Robert Frost, A Witness Tree (Henry Holt 1942).

The World is reticent and coy. Yet, now and then, it unexpectedly sends us a message, makes a brief appearance. For Frost, these are not divine revelations. I cannot imagine him using the word "immanence." "For once, then, something." But what? ". . . and that was all." Nothing more? On the other hand, a common phrase does come to mind: "Make the most of it."

I have my own story related to "The Most of It," which I recounted here in August of 2014. Many years before I encountered the poem, I spent a summer living beside a lake in northern Idaho. On a regular basis, a moose would enter the lake from the opposite shore, swim across, emerge from the water near the cabin, and walk off into the woods. Imagine my delight when I first read "The Most of It."

"All I have been able to do is to walk and go on walking, remember, glimpse, forget, try again, rediscover, become absorbed. I have not bent down to inspect the ground like an entomologist or a geologist; I've merely passed by, open to impressions. I have seen those things which also pass -- more quickly or, conversely, more slowly than human life. Occasionally, as if our movements had crossed -- like the encounter of two glances that can create a flash of illumination and open up another world -- I've thought I had glimpsed what I should have to call the still centre of the moving world. Too much said? Better to walk on . . ."

Philippe Jaccottet (translated by Mark Treharne), in Philippe Jaccottet, Landscapes with Absent Figures (Delos Press 1997), page 4 (ellipses in original text).

Albert Woods (1871-1944), "A Peaceful Valley, Whitewell"

At this time of year, as I walk in the afternoon down a path between two wide meadows, swallows climb and dive and curve all around me, then skim just above the tall grass on each side of the path, feeding on insects. Last week, on another path, I saw a small, dark field mouse hurry into a clump of wild sweet peas, now in purple bloom. Yesterday evening, a raccoon climbed up into the cherry tree in the back garden, where the fruit is now ripe. Two of the neighborhood crows loudly complained about this activity. This morning I saw a robin walking in the garden, holding a cherry in its beak.

"I have learned from long experience that there is nothing that is not marvellous and that the saying of Aristotle is true -- that in every natural phenomenon there is something wonderful, nay, in truth, many wonders. We are born and placed among wonders and surrounded by them, so that to whatever object the eye first turns, the same is wonderful and full of wonders, if only we will examine it for a while."

John de Dondis, quoted in John Stewart Collis, The Worm Forgives the Plough (The Akadine Press 1997), page 170. "John de Dondis" is the anglicized name of Giovanni de' Dondi (c. 1330-1388).

Little things. Glimmers and glimpses.

Fireflies flying

in gaps between branches --

a grove of stars.

Ikkadō Jōa (1501-1562) (translated by Steven Carter), in Steven Carter (editor), Haiku Before Haiku: From the Renga Masters to Bashō (Columbia University Press 2011), page 108.

Fred Stead (1863-1940), "River at Bingley, Yorkshire"

2 comments:

What a lovely pos containing two of my favourite Frost poems. The sentiments you express are a mirror of my own. I love the final painting too for I know the scene well as I live not too far from it. Alas, an arterial road has been built close by, but Bingley remains a pleasant and scenic place. Lee Hanson.

Mr. Hanson: I'm happy to hear from you again, and am pleased to know you are still stopping by. Thank you for the kind words about the post. I'm also quite fond of the two poems. They complement each other well, don't they?

As for the painting: as I recall, I have posted a few other paintings here which have a Yorkshire locale, and which you have noted are in your neck of the woods. You are fortunate. Perhaps I have been, or will be, born in Yorkshire in another life. I'm pleased to know that Bingley survives. I looked at some photos of it on the internet after receiving your comment, and I recognize the river, the church tower, and the stone buildings (old warehouses?) beside the river from the painting.

Thank you very much for your long-time presence here, and for visiting again.

Post a Comment