Any time is a good time to contemplate the fleeting nature of our life. But the beginning of a new year is an especially appropriate time to do so. There is a sense of the slate having been wiped clean (well, as much as it can be), and of a fresh opportunity to fully appreciate the yet-unused moments that lie before us.

I had first thought to write: "Any time is a good time to contemplate the fleeting nature of our

soul." But I thought better of it. There is no doubt that life is fleeting. But is that true of the soul?

I realize that, for some moderns, the very idea of the existence of a "soul" is beyond the realm of possibility, and is viewed by them as an outdated superstition of which they have been disabused. I'm afraid that I have not been disabused. Thus, the following poem is not simply a historical curiosity for me. Nor is it anachronistic. And I find it worth a visit at the turning of the year.

Persuasion

"Man's life is like a Sparrow, mighty King!

That -- while at banquet with your Chiefs you sit

Housed near a blazing fire -- is seen to flit

Safe from the wintry tempest. Fluttering,

Here did it enter; there, on hasty wing,

Flies out, and passes on from cold to cold;

But whence it came we know not, nor behold

Whither it goes. Even such, that transient Thing,

The human Soul; not utterly unknown

While in the Body lodged, her warm abode;

But from what world She came, what woe or weal

On her departure waits, no tongue hath shown;

This mystery if the Stranger can reveal,

His be a welcome cordially bestowed!"

William Wordsworth, in Abbie Findlay Potts,

The Ecclesiastical Sonnets of William Wordsworth: A Critical Edition (Yale University Press 1922).

"The Stranger" referred to in line 13 is Paulinus, who, in 601, was sent to England by Pope Gregory I to convert the inhabitants to Christianity. The scene took place during Paulinus's visit to King Edwin of Northumbria in 625 or thereabouts (the date is not certain).

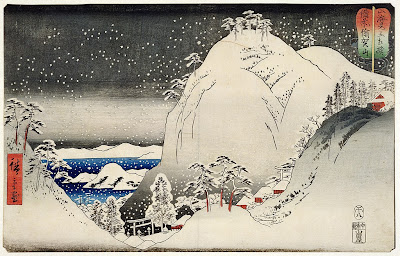

Utagawa Hiroshige (1797-1858), "Mount Yuga in Bizen Province"

The incident upon which Wordsworth's sonnet is based is found in the Venerable Bede's

Ecclesiastical History of the English People (c. 731):

"The present life of man upon earth, O king, seems to me, in comparison with that time which is unknown to us, like to the swift flight of a sparrow through the house wherein you sit at supper in winter, with your ealdormen and thegns, while the fire blazes in the midst, and the hall is warmed, but the wintry storms of rain or snow are raging abroad. The sparrow, flying in at one door and immediately out at another, whilst he is within, is safe from the wintry tempest; but after a short space of fair weather, he immediately vanishes out of your sight, passing from winter into winter again. So this life of man appears for a little while, but of what is to follow or what went before we know nothing at all. If, therefore, this new doctrine tells us something more certain, it seems justly to deserve to be followed."

A. M. Sellar (translator),

Bede's Ecclesiastical History of the English People (G. Bell and Sons 1917), pages 116-117.

In her edition of

The Ecclesiastical Sonnets, Potts suggests that, based upon certain verbal parallels in his sonnet, Wordsworth likely first encountered Bede's story in

The Church History of Britain (1655) by Thomas Fuller (1608-1661). Potts,

The Ecclesiastical Sonnets of William Wordsworth: A Critical Edition, page 224. Here is Fuller's version:

"Man's life," said he, "O King, is like unto a little sparrow, which, whilst your majesty is feasting by the fire in your parlor with your royal retinue, flies in at one window, and out at another. Indeed, we see it that short time it remaineth in the house, and then is it well sheltered from wind and weather; but presently it passeth from cold to cold; and whence it came, and whither it goes, we are altogether ignorant. Thus, we can give some account of our soul during its abode in the body, whilst housed and harbored therein; but where it was before, and how it fareth after, is to us altogether unknown. If therefore Paulinus's preaching will certainly inform us herein, he deserveth, in my opinion, to be entertained."

Ibid, page 224.

Utagawa Hiroshige, "Uraga in Sagami Province"

The flight of the sparrow in Bede's chronicle brings to mind the death-bed poem of the Emperor Hadrian (76-138), which begins with the line "

animula vagula blandula." The line has been variously translated as: "My little wand'ring sportful Soule" (John Donne, 1611); "My soul, my pleasant soul and witty" (Henry Vaughan, 1652); "Little soul so sleek and smiling" (Stevie Smith, 1966). Adrian Poole and Jeremy Maule (editors),

The Oxford Book of Classical Verse in Translation (Oxford University Press 1995), pages 508-509. Very sparrow-like.

The following two translations of the entire poem go together quite well with the sparrow in King Edwin's Northumbrian hall, I think.

Ah! gentle, fleeting, wav'ring sprite,

Friend and associate of this clay!

To what unknown region borne,

Wilt thou, now, wing thy distant flight?

No more, with wonted humour gay,

But pallid, cheerless, and forlorn.

George Gordon, Lord Byron,

Hours of Idleness (1807).

Poor little, pretty, flutt'ring thing,

Must we no longer live together?

And dost thou prune thy trembling wing,

To take thy flight thou know'st not whither?

Thy humorous vein, thy pleasing folly

Lies all neglected, all forgot:

And pensive, wav'ring, melancholy,

Thou dread'st and hop'st thou know'st not what.

Matthew Prior,

Poems on Several Occasions (1709).

Utagawa Hiroshige, "Ishiyakushi"

As for the fate of the soul, this poem, which has appeared here before, is worth revisiting on this occasion.

The Soul's Progress

It enters life it knows not whence; there lies

A mist behind it and a mist before.

It stands between a closed and open door.

It follows hope, yet feeds on memories.

The years are with it, and the years are wise;

It learns the mournful lesson of their lore.

It hears strange voices from an unknown shore,

Voices that will not answer to its cries.

Blindly it treads dim ways that wind and twist;

It sows for knowledge, and it gathers pain;

Stakes all on love, and loses utterly.

Then, going down into the darker mist,

Naked, and blind, and blown with wind and rain,

It staggers out into eternity.

Arthur Symons,

Days and Nights (1889).

There is no mistaking the vital stream that runs from Hadrian through Bede through Wordsworth through Symons. This progression seems absolutely fresh and contemporary to me. It makes modern irony and know-it-allness seem stodgy, old-fashioned, and -- no other word fits -- soulless.

Utagawa Hiroshige, "Snow Falling on a Town"