It is that time of year once again: I step out the front door, walk for an hour or so, and return, all the while accompanied by birdsong (occasionally punctuated by a crow's caw-caw-caw from off in the distance, or from directly above -- out of the blue). In the meadows, solitary birds now and then fly up out of the wild grass or hop down a path, voiceless. But the surrounding woods are full of unseen, unceasing choristers.

For Their Own Sake

Come down to the woods where the buds burst

Into fragrances, where the leaves make havoc

Of cloudy skies. Listen to birds

Obeying their instincts but also singing

For singing's sake. By the same token

Let us be silent for silence's sake,

Watching the buds, hearing the break

Free of fledgelings, the branches swinging

The sun, and never a word need be spoken.

Elizabeth Jennings, Consequently I Rejoice (Carcanet 1977).

This comes to mind: "the calm oblivious tendencies/Of Nature." (William Wordsworth, The Excursion, Book I ("The Wanderer"), lines 963-964 (1814).) One of those gnomic utterances found so often in the younger Wordsworth (of whom I am fond, although I recognize that others may find him tiresome). "Oblivious" has always given me pause. For instance, how does one reconcile it with immanence? One can lose one's way in trying to unravel the euphoria and contradictions of the marvelous Wordsworthian-Coleridgean pantheism that emerged in 1797, and flourished for a few charmed years.

Jennings' poem suggests a reasonable approach: "oblivious" or not, the beautiful particulars of the World are enough in themselves, "for their own sake." Her final words are exactly right: ". . . and never a word need be spoken." For another perspective, we can turn to a lovely poem that has appeared here on more than one occasion: a different note, but in the same neighborhood.

Reciprocity

I do not think that skies and meadows are

Moral, or that the fixture of a star

Comes of a quiet spirit, or that trees

Have wisdom in their windless silences.

Yet these are things invested in my mood

With constancy, and peace, and fortitude,

That in my troubled season I can cry

Upon the wide composure of the sky,

And envy fields, and wish that I might be

As little daunted as a star or tree.

John Drinkwater, Tides (Sidgwick & Jackson 1917).

Winter over, the robins no longer gather in flocks. Leaving a meadow and passing through a dark grove of pines, one hears them singing high overhead, each in its own tree.

On a breezy day, the new deep-green grass in the meadows turns silver as it sways and flows in the morning or afternoon sunlight. And the sound of the rising and falling and threshing silver-green waves, how does one describe that? A rustling? A whispering? A sighing? A soughing? A susurration? All of the above. But words ultimately fail, don't they? Elizabeth Jennings is correct: ". . . and never a word need be spoken." You simply have to be there. No words are necessary. No words are sufficient.

My favorite poem of May is Philip Larkin's "The Trees," to which I owe "threshing" in the paragraph immediately above. The source is the poem's final stanza: "Yet still the unresting castles thresh/In fullgrown thickness every May./Last year is dead, they seem to say,/Begin afresh, afresh, afresh." (Philip Larkin, High Windows (Faber and Faber 1974).) However, when it comes to the grass of the meadows in May, I return each year to this:

Consider the Grass Growing

Consider the grass growing

As it grew last year and the year before,

Cool about the ankles like summer rivers,

When we walked on a May evening through the meadows

To watch the mare that was going to foal.

Patrick Kavanagh, Collected Poems (edited by Antoinette Quinn) (Penguin 2005). The poem was first published in The Irish Press on May 21, 1943. Ibid, page 271.

May is an effulgent yet wistful month. It does not have the wistful bittersweetness, or the bittersweet wistfulness, of, say, September or October: Spring continues to burgeon. But the fallen cherry, plum, and magnolia petals lay scattered on the sidewalks, strewn across the grass. On the other hand, along the paths and in the glades five-petaled pink wild roses (called the "Nootka rose" in this part of the world) and purple lupines are in bloom. The "unresting castles" soon will be in their "fullgrown thickness" of green. Ah, yes: "The paradise of Flowers' and Butterflies' Spirits." (Samuel Taylor Coleridge, in Kathleen Coburn (editor), The Notebooks of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Volume 1: 1794-1804 (Pantheon 1957), Notebook Entry 1736 (December 1803).)

The One

Green, blue, yellow and red --

God is down in the swamps and marshes,

Sensational as April and almost incred-

ible the flowering of our catharsis.

A humble scene in a backward place

Where no one important ever looked;

The raving flowers looked up in the face

Of the One and the Endless, the Mind that has baulked

The profoundest of mortals. A primrose, a violet,

A violent wild iris -- but mostly anonymous performers,

Yet an important occasion as the Muse at her toilet

Prepared to inform the local farmers

That beautiful, beautiful, beautiful God

Was breathing His love by a cut-away bog.

Patrick Kavanagh, Collected Poems. By splitting "incredible" in lines three and four, Kavanagh is able to contrive a sonnet. (And the rhyming of "marshes" and "catharsis" in lines two and four is no mean feat either.) "The One" was written during Kavanagh's ecstatic "Canal Bank period" of 1955 through 1958, which was prompted by his survival after a brush with lung cancer (with accompanying surgery) in March and April of 1955. Ibid, page 284. The poem was first published in the journal Nonplus in October of 1959. Ibid, page 286.

Anne Isabella Brooke (1916-2002)

"Wharfedale From Above Bolton Abbey" (c. 1954)

"All things around us are asking for our apprehension, working for our enlightenment. But our thoughts are of folly. What is worse, every day, and many times in the day, we are enlightened, we are Buddha, a poet, -- but do not know it, and remain an ordinary man. For our sake haiku isolate, as far as it is possible, significance from the mere brute fact or circumstance. It is a single finger pointing to the moon. If you say it is only a finger, and often not a very beautiful one at that, this is so. If the hand is beautiful and bejeweled, we may forget what it is pointing at. Recording a conversation with Blake, [Henry] Crabb Robinson gives us an example of the indifference, or rather the cowardice, of average human nature, in its failure to recognize truth, poetry, when confronted with it in its unornamented form; the lines he quotes from Wordsworth are a "haiku." 'I had been in the habit, when reading this marvellous Ode to friends, to omit one or two passages, especially that beginning,

But there's a Tree, of many, one,

A single field

That I have looked upon,

lest I should be rendered ridiculous, being unable to explain precisely what I admired. Not that I acknowledged this to be a fair test. But with Blake I could fear nothing of the kind. And it was this very stanza which threw him almost into a hysterical rapture'."

R. H. Blyth, Haiku, Volume III: Summer-Autumn (Hokuseido Press 1952), pages i-ii. The passage quoted by Blyth from Henry Crabb Robinson's papers may be found in Arthur Symons, William Blake (Archibald Constable and Company 1907), pages 296-297 ("Extracts from the Diary, Letters, and Reminiscences of Henry Crabb Robinson"). The "Ode" referred to by Crabb Robinson is "Ode: Intimations of Immortality from Recollections of Early Childhood."

Of course, Blyth's intention is to make a case for the unique beauty and power of haiku. This was, in fact, his mission in life. In my humble opinion, Blyth is entirely correct in his assessment of the Beauty and Truth that may be found in the best haiku, and of the ability of haiku to provide enlightenment (regardless of whether or not such enlightenment occurs within the context of Buddhism). However, as Blyth suggests in this passage (and as he makes clear throughout his writings), the best poetry, in all places and at all times, "is a single finger pointing to the moon." Thus, his observations on haiku are intertwined with references to, and comparisons with, English poetry and Chinese poetry in particular, and world literature and philosophy in general. This catholic approach is one of the features which (again, in my humble opinion) makes his works so interesting, provocative, and, yes, wise, and gives them such charm.

All of which leads me (lengthily) to this:

Now

The longed-for summer goes;

Dwindles away

To its last rose,

Its narrowest day.

No heaven-sweet air but must die;

Softlier float,

Breathe lingeringly

Its final note.

Oh, what dull truths to tell!

Now is the all-sufficing all

Wherein to love the lovely well,

Whate'er befall.

Walter de la Mare, O Lovely England and Other Poems (Faber and Faber 1953).

"Now" perfectly complements the observations made by Blyth in the passage quoted above. "Now is the all-sufficing all/Wherein to love the lovely well,/Whate'er befall." Consider this from Blyth: "All things around us are asking for our apprehension, working for our enlightenment." Or this: "every day, and many times in the day, we are enlightened, we are Buddha, a poet, -- but do not know it, and remain an ordinary man." As I noted above, although Blyth is making a case for the beauty and power of haiku, his observations are arguably applicable to all of the best poetry (although I certainly agree that haiku does have a special beauty and power that is the product of a unique and wonderful culture and language).

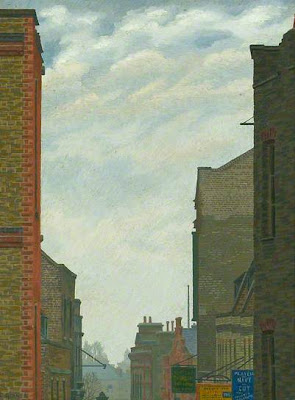

Leonard Pike (1887-1959), "The Chasing Shadows"

Who knows why we are here in this "paradise of Flowers' and Butterflies' Spirits." During the short time we have, we should pay attention, and -- above all -- be grateful. Speaking for myself, I fail each day. But the poets daily remind me to attend to the World.

Night

That shining moon -- watched by that one faint star:

Sure now am I, beyond the fear of change,

The lovely in life is the familiar,

And only the lovelier for continuing strange.

Walter de la Mare, Memory and Other Poems (Constable 1938).

One sometimes feels at a loss. But then you happen upon something like this:

A night of stars;

The cherry blossoms are falling

On the water of the rice seedlings.

Buson (1716-1784) (translated by R. H. Blyth), in R. H. Blyth, Haiku, Volume II: Spring (Hokuseido Press 1950), page 170.

And the reflections of the stars float with the fallen cherry petals on the water, among the rice seedlings.

Herbert Hughes-Stanton (1870-1937)

"The Mill in the Valley" (1892)