I believe that, apart from Abraham Lincoln, Ulysses S. Grant was the most admirable and most interesting character to emerge from the American Civil War. (I am speaking of those on the national stage, not of the thousands of admirable and interesting characters -- on both sides -- who were involved in the War.)

As I have noted before, the best description of Grant comes from Theodore Lyman (who served as an aide to Major-General George Meade, commander of the Army of the Potomac): "He is the concentration of all that is American."

It is interesting that this description comes from Lyman: he was born into Boston high society, graduated from Harvard, and his letters and his journal entries tend to be dismissive of military officers from "the West" (i.e., anyone who did not come from the East Coast). He considered them uneducated, unsophisticated, and uncouth. However, Lyman has nothing but good things to say about Grant. He cannot avoid a bit of condescension now and then, but it is clear that Lyman recognized that he was in the presence of a remarkable man.

In the late summer of 1864, Grant's headquarters were located in City Point, Virginia, on the James River. On August 6, a munitions barge anchored in the James exploded due to Confederate sabotage. Lyman wrote this about the incident:

"This morning we heard a heavy explosion towards City Point, and there came a telegraph in a few minutes that an ordnance barge had blown up with much loss of life. Rosie, Worth, Cavada and Cadwalader were in a tent at Grant's headquarters when suddenly there was a great noise, and a 12-pounder shot came smash into the mess-chest! They rushed out -- it was raining shot, shell, timbers, and saddles (of which there had been a barge-load near)! Two dragoons were killed near them. They saw just then a man running towards the explosion -- the only one -- it was Grant! and this shows his character well."

David Lowe (editor), Meade's Army: The Private Notebooks of Lt. Col. Theodore Lyman (2007), page 248. (The emphases are in the original.)

Although Grant was "noticeably an intrepid man" (Lyman's words again), he had no vainglory about him. He was quiet, steady, and -- above all else -- supremely imperturbable. When Grant went east to assume overall command of the Union armies, William Tecumseh Sherman wrote to his brother John (who was a United States Senator): "Give Grant all the support you can. . . . He will fight, and the Army of the Potomac will have all the fighting they want. . . . His simplicity and modesty are natural and not affected."

Charles W. Reed

"Grant Whittling During The Battle Of The Wilderness"

May 5, 1864

In May of 1864, Grant began his first campaign in Virginia against Robert E. Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia. The Army of the Potomac was immediately battered by Lee for two days in the Battle of the Wilderness. In the first three years of the War, each prior commander of the Army of the Potomac had turned back to the north after coming up against Lee in Virginia. Not Grant. He continued to move south.

On the night of the second day of the battle, Grant learned that Henry Wing, a reporter from The New York Tribune, was returning to Washington to file his story on the battle. Grant took Wing aside, put his hand on Wing's shoulder, and, "in a low tone," said: "Well, if you see the President, tell him from me that, whatever happens, there will be no turning back."

Wing returned to Washington (a dangerous trip), and he was then brought to the White House to provide whatever information he had about the battle. (Given the state of communication in those days, information was scarce, even for Lincoln.) Wing provided a 30-minute report to Lincoln and an assembled group. As the others left, Wing told Lincoln that he had a "personal word" for him. Alone with Lincoln, Wing then repeated Grant's message. According to Wing, "Mr. Lincoln put his great, strong arms about me and, carried away in the exuberance of his gladness, imprinted a kiss upon my forehead." Henry Wing, When Lincoln Kissed Me: A Story of the Wilderness Campaign (1913), pages 36-39.

Cold Harbor, Virginia, 1864

Showing posts with label Ulysses S. Grant. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Ulysses S. Grant. Show all posts

Sunday, June 5, 2011

Saturday, October 30, 2010

On The Eve Of An Election

Please note: this is not a political blog and this is not a political post. Rather, it is a post about one's nation, and about the political class (not the people) of one's nation. The following poem is by C. H. Sisson, an Englishman who was described, in the Telegraph's 2003 obituary, as a "doughty defender of traditional Anglicanism" who held "unfashionable high Tory views." (As I have said before: A man after my own heart, even though I am not an Englishman, an Anglican, or a Tory.)

Thinking of Politics

Land of my fathers, you escape me now

And yet I will in no wise let you go:

Let none imagine that I do not know

How little sight of you the times allow.

Yet you are there, and live, no matter how

The troubles which surround you seem to grow:

The steps of ancestors are always slow,

But always there behind the current row,

And always and already on the way:

They will be heard on the appropriate day.

C. H. Sisson, What and Who (1994).

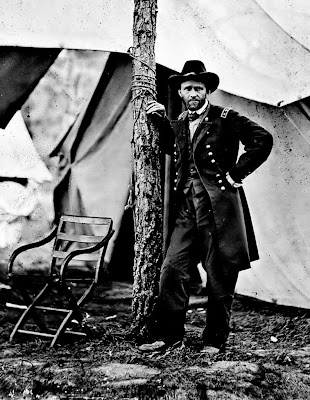

A future presidential candidate at the age of 42.

Headquarters of the Army of the Potomac.

Cold Harbor, Virginia. June, 1864.

Thinking of Politics

Land of my fathers, you escape me now

And yet I will in no wise let you go:

Let none imagine that I do not know

How little sight of you the times allow.

Yet you are there, and live, no matter how

The troubles which surround you seem to grow:

The steps of ancestors are always slow,

But always there behind the current row,

And always and already on the way:

They will be heard on the appropriate day.

C. H. Sisson, What and Who (1994).

A future presidential candidate at the age of 42.

Headquarters of the Army of the Potomac.

Cold Harbor, Virginia. June, 1864.

Monday, June 14, 2010

"He Is The Concentration Of All That Is American"

I greatly admire Ulysses S. Grant. Why? A first-hand observer of Grant answers that question much more eloquently than I can. Theodore Lyman served as an aide to Major-General George Meade, commander of the Army of the Potomac. Grant was in the field with the Army from 1864 until the end of the war. Lyman saw Grant nearly every day during that period. In a June 12, 1864, letter to his wife, Lyman wrote of Grant: "He is the concentration of all that is American." (George Agassiz (editor), Meade's Headquarters, 1863-1865: Letters of Colonel Theodore Lyman from The Wilderness to Appomattox (1922), page 156.)

T. Harry Williams writes:

Grant's life is, in some ways, the most remarkable one in American history. There is no other quite like it.

. . .

People were always looking for visible signs of greatness in Grant. Most of them saw none and were disappointed. . . . Charles Francis Adams, Jr., grasped immediately the essence of Grant -- that here was an extraordinary man who looked ordinary. Grant could pass for a "dumpy and slouchy little subaltern," Adams thought, but nobody could watch him without concluding that he was a "remarkable man. . . . in a crisis he is one against whom all around, whether few in number or a great army as here, would instinctively lean. He is a man of the most exquisite judgment and tact."

T. Harry Williams, McClellan, Sherman and Grant (1962), pages 79-83.

As he was dying of cancer, Grant -- in a final act of fortitude and integrity -- wrote his memoirs in order to pay off his debts and to provide for the financial security of his family. He completed the memoirs less than a week before his death.

Grant begins: "My family is American, and has been for generations, in all its branches, direct and collateral."

Grant writing his memoirs

T. Harry Williams writes:

Grant's life is, in some ways, the most remarkable one in American history. There is no other quite like it.

. . .

People were always looking for visible signs of greatness in Grant. Most of them saw none and were disappointed. . . . Charles Francis Adams, Jr., grasped immediately the essence of Grant -- that here was an extraordinary man who looked ordinary. Grant could pass for a "dumpy and slouchy little subaltern," Adams thought, but nobody could watch him without concluding that he was a "remarkable man. . . . in a crisis he is one against whom all around, whether few in number or a great army as here, would instinctively lean. He is a man of the most exquisite judgment and tact."

T. Harry Williams, McClellan, Sherman and Grant (1962), pages 79-83.

As he was dying of cancer, Grant -- in a final act of fortitude and integrity -- wrote his memoirs in order to pay off his debts and to provide for the financial security of his family. He completed the memoirs less than a week before his death.

Grant begins: "My family is American, and has been for generations, in all its branches, direct and collateral."

Grant writing his memoirs

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)