Once again, dear readers, it is time to return to my favorite poem of April. Discovering a poem we love is a wonderful thing, but even more wonderful is the poem's continuing presence in our life over the years. We are not the same, the world is not the same, as when we last visited the poem. Who knows what awaits us when we arrive the next time?

Wet Evening in April

The birds sang in the wet trees

And as I listened to them it was a hundred years from now

And I was dead and someone else was listening to them.

But I was glad I had recorded for him the melancholy.

Patrick Kavanagh, Collected Poems (edited by Antoinette Quinn) (Penguin 2005). The poem was first published in Kavanagh's Weekly on April 19, 1952. Ibid, page 280.

No doubt I am a creature of habit, stuck in my settled ways. But "Wet Evening in April" never ceases to move me, whether I return to it in April as a ritual, or whether it unaccountably rises to the surface of its own accord, in any season, at any moment.

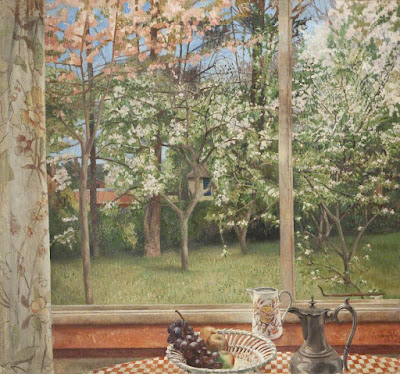

Richard Eurich (1903-1992), "The Window"

"But it is a sort of April weather life that we lead in this world. A little sunshine is generally the prelude to a storm." (William Cowper, letter to Walter Bagot (January 3, 1787), in James King and Charles Ryskamp (editors), The Letters and Prose Writings of William Cowper, Volume III: Letters 1787-1791 (Oxford University Press 1982), pages 5-6.) So it was in this part of the world yesterday afternoon, as I walked through alternating showers and sunlight, the waters of Puget Sound by turns dark gray and dazzling. So it is in the world at large.

Withal, there is an ever-present thread of beauty and truth running through our April weather life, through the April weather life of the world. Poetry is an instance of the existence of that thread.

Homage to Arthur Waley

Seattle weather: it has rained for weeks in this town,

The dampness breeding moths and a gray summer.

I sit in the smoky room reading your book again,

My eyes raw, hearing the trains steaming below me

In the wet yard, and I wonder if you are still alive.

Turning the worn pages, reading once more:

"By misty waters and rainy sands, while the yellow dusk thickens."

Weldon Kees, in The Collected Poems of Weldon Kees (edited by Donald Justice) (University of Nebraska Press 1975). The poem was first published in 1943.

As long time (and much appreciated!) readers of this blog may recall, Arthur Waley is one of my favorite translators of Chinese poetry into English (along with Burton Watson), and his translations have appeared here on many occasions. Thus, I was delighted when I first came across Kees' poem (most likely on a rainy day in Seattle).

The quotation from Waley in the final line is from Waley's translation of a four-line poem (chüeh-chü) by Po Chü-i:

A bend of the river brings into view two triumphal arches;

That is the gate in the western wall of the suburbs of Hsün-yang.

I have still to travel in my solitary boat three or four leagues --

By misty waters and rainy sands, while the yellow dusk thickens.

Po Chü-i (772-846) (translated by Arthur Waley), in Arthur Waley, One Hundred and Seventy Chinese Poems (Constable 1918). The poem is untitled. It appears in a two-poem sequence titled "Arriving at Hsün-yang." (By the way, Waley was in fact "still alive" when Kees wrote the poem: he died in 1966 at the age of 76.)

Richard Eurich, "The Rose" (1960)

Patrick Kavanagh meditates upon someone not yet born who will be listening to birds singing in wet trees in April a hundred years in the future, when Kavanagh will be long gone. By virtue of the art of Arthur Waley, Weldon Kees reads a poem written by Po Chü-i a thousand years ago in China. However fragile and contingent the world is, we mustn't forget this abiding thread.

To a Poet a Thousand Years Hence

I who am dead a thousand years,

And wrote this sweet archaic song,

Send you my words for messengers

The way I shall not pass along.

I care not if you bridge the seas,

Or ride secure the cruel sky,

Or build consummate palaces

Of metal or of masonry.

But have you wine and music still,

And statues and a bright-eyed love,

And foolish thoughts of good and ill,

And prayers to them who sit above?

How shall we conquer? Like a wind

That falls at eve our fancies blow,

And old Maeonides the blind

Said it three thousand years ago.

O friend unseen, unborn, unknown,

Student of our sweet English tongue,

Read out my words at night, alone:

I was a poet, I was young.

Since I can never see your face,

And never shake you by the hand,

I send my soul through time and space

To greet you. You will understand.

James Elroy Flecker, in John Squire (editor), The Collected Poems of James Elroy Flecker (Secker and Warburg 1947).

Richard Eurich, "The Road to Grassington" (1971)

.jpg)