Swallows Flown

Whence comes that small continuous silence

Haunting the livelong day?

This void, where a sweetness, so seldom heeded,

Once ravished my heart away?

As if a loved one, too little valued,

Had vanished -- could not stay?

Walter de la Mare, Memory and Other Poems (Constable 1938).

None of this comes as a surprise. Still, every year there is a pang. Something along these lines: "Snowy boughs by the eastern palisade set me pondering --/in a lifetime how many springs do we see?" (Su Tung-p'o (1036-1101) (translated by Burton Watson), "Pear Blossoms by the Eastern Palisade.") A time comes when you realize with certainty that the seasons you have seen far outnumber the seasons that remain to you. This is not a bad thing to take to heart.

The Last Swallow

The robin whistles again. Day's arches narrow,

Tender and quiet skies lighten the withering flowers.

The dark of winter must come. . . . But that tiny arrow,

Circuiting high in the blue -- the year's last swallow,

Knows where the coast of far mysterious sun-wild Africa lours.

Walter de la Mare, Inward Companion (Faber and Faber 1950).

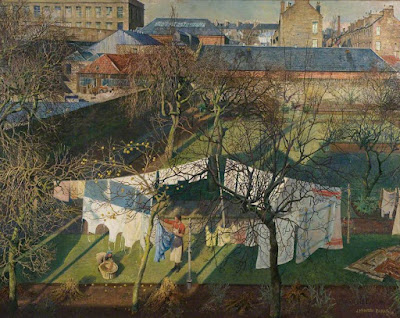

Alfred Thornton (1863-1939)

"Hill Farm, Painswick, Gloucestershire"

The dragonflies seem to have vanished as well. I remember an afternoon this past summer when I stood in the middle of a field as the swallows climbed and dived and swerved and skimmed just above the tops of the green meadow grasses. On that day, the dragonflies were also out in the field, and they and the swallows circled around me. Please bear with me, but, as I stood there, I couldn't help but think of this: "At the still point of the turning world." (T. S. Eliot, "Burnt Norton.") (Fortunately, it can't be helped: certain of the poems we loved when we were young never leave us, do they? They remain within us always, waiting.)

Being but man, forbear to say

Beyond to-night what thing shall be,

And date no man's felicity.

For know, all things

Make briefer stay

Than dragonflies, whose slender wings

Hover, and whip away.

Simonides (556-467 B.C.) (translated by T. F. Higham), in T. F. Higham and C. M. Bowra (editors), The Oxford Book of Greek Verse in Translation (Oxford University Press 1938), page 234.

A few years after coming across Simonides' dragonflies, I happened upon this, and the two are now forever linked:

"October 6, 1940. Late in the season as it is, a dragonfly has appeared and is flying around me. Keep on flying as long as you can -- your flying days will soon be over."

Taneda Santōka (1882-1940) (translated by Burton Watson), in Burton Watson (editor), For All My Walking: Free-Verse Haiku of Taneda Santōka with Excerpts from His Diaries (Columbia University Press 2003), page 102. Watson provides this note to the passage: "This is the last entry in Santōka's diary, written four days before his death." Ibid, page 102.

John Aldridge (1905-1983), "The Pant Valley, Summer" (1960)

Whenever the topic at hand is the evanescence of the beautiful particulars of the World, it seems that Edward Thomas hovers over my shoulder. And often, as in the case of this post, he is in the company of his friend, Walter de la Mare. I don't know what I would do without the two of them.

How at Once

How at once should I know,

When stretched in the harvest blue

I saw the swift's black bow,

That I would not have that view

Another day

Until next May

Again it is due?

The same year after year --

But with the swift alone.

With other things I but fear

That they will be over and done

Suddenly

And I only see

Them to know them gone.

Edward Thomas, The Annotated Collected Poems (Edna Longley, editor) (Bloodaxe Books 2008), page 131.

Swifts and swallows go well together. Antic sprites that frolic and then vanish.

Alfred Thornton, "The Upper Severn"

A thought by Thomas Hardy comes to mind: "Earth never grieves!" ("Autumn in King's Hintock Park," in Time's Laughingstocks and Other Verses (Macmillan 1909).) One can find comfort and equanimity in the thought that, once our short time in the World is over, the seasons will continue to come and go without us, with their generations of leaves and birds and clouds.

At Night on a Journey

Bell-sounds night after night -- falling on whose ears?

The traveler's dream: forty years pass in an instant:

Sitting up by shutters under the pines, I forget "I" --

Clouds issue from the peaks, the moon courses the heavens.

Ryūshū Shūtaku (1308-1388) (translated by Marian Ury), in Marian Ury (editor), Poems of the Five Mountains: An Introduction to the Literature of the Zen Monasteries (Center for Japanese Studies, University of Michigan 1992), page 59. Ury includes this note to the poem: "The second line refers to a Chinese folktale that became popular in Japan. A man who has come to the capital to seek his fortune lies down for a nap and experiences in dream all the vicissitudes of a long, glorious but ultimately tragic official career; awaking, he discovers that no more time has passed than it has taken for his supper of yellow millet to cook." Ibid, page 59.

When I walk down an avenue of trees on a sunny day, my attention is usually focused upward, on the leaves turning in the wind, set against blue and gold. But one afternoon this past summer my eyes were drawn to the swaying shadows of branches on the asphalt pathway before me. A beautiful, ever-changing world of its own, replicating in its own fashion the beautiful, ever-changing world overhead. After a few moments passed, I noticed down on the sunlit pathway the small but distinct shadow of a butterfly that was balancing out on the shadow of the far tip of one of the moving branches. As I watched, the shadow of the butterfly flew away. I looked up, but I saw no butterfly in the sky.

On the Road on a Spring Day

There is no coming, there is no going.

From what quarter departed? Toward what quarter bound?

Pity him! in the midst of his journey, journeying --

Flowers and willows in spring profusion, everywhere fragrance.

Ryūsen Reisai (d. 1365) (translated by Marian Ury), Ibid, page 33. Ury includes this note to the poem: "The poem begins with a Zen truism, which is expanded into a personal statement." Ibid, page 33.

John Aldridge, "Stubble Field, Thaxted" (1968)