People are few;

A leaf falls here,

Falls there.

Issa (1763-1828) (translated by R. H. Blyth), in R. H. Blyth, Haiku, Volume 4: Autumn-Winter (Hokuseido Press 1952), page 364.

A single leaf falls in a sunlight-pierced, shadowed grove, joining its predecessors. I cannot help but return to the lines from Yeats which appeared in my most recent post: ". . . and the yellow leaves/Fell like faint meteors in the gloom." (W. B. Yeats, "Ephemera.") There is something to be said for waning autumn.

Leaves falling,

Lie one on another;

The rain beats on the rain.

Gyōdai (1732-1793) (translated by R. H. Blyth), in R. H. Blyth, Haiku, Volume 4: Autumn-Winter, page 365.

The haiku by Issa and Gyōdai are statements of fact. Lovely statements of fact. Records of two evanescent moments made by two evanescent human beings. But there is much more afoot. "The real nature of each thing, and more so, of all things, is a poetical one. . . . Haiku shows us what we knew all the time, but did not know we knew; it shows us that we are poets in so far as we live at all." (R. H. Blyth, Haiku, Volume 1: Eastern Culture (Hokuseido Press 1949), page x.)

And this:

"In old-fashioned novels, we often have the situation of a man or a woman who realizes only at the end of the book, and usually when it is too late, who it was that he or she had loved for many years without knowing it. So a great many haiku tell us something that we have seen but not seen. They do not give us a satori, an enlightenment; they show us that we have had an enlightenment, had it often, -- and not recognized it."

R. H. Blyth, Haiku, Volume 3: Summer-Autumn (Hokuseido Press 1952), page 322 (the italics are in the original text).

In noting that Issa's and Gyōdai's haiku are "statements of fact," I am not suggesting that the poems are emotionless observations, devoid of feeling. Any fine haiku is an embodiment of kokoro, a Japanese word (based on the Chinese character for the Chinese word xin) which can mean "heart," "mind," or "spirit" or, in certain contexts, all three of them at once: heart-mind-spirit. Thus, the distinctive melancholy of autumn inhabits both of the two haiku: that combination of heartbreaking beauty and resigned acceptance each of us knows so well.

Alexander Jamieson (1873-1937)

"The Old Mill, Weston Turville" (1927)

Autumn's particular form of melancholy is, not surprisingly, present in my favorite autumnal poem by Thomas Hardy. As is so often the case (at least for me) when reading Hardy's poetry, the poem contains a line which, once encountered, stays with you for a lifetime.

Autumn in King's Hintock Park

Here by the baring bough

Raking up leaves,

Often I ponder how

Springtime deceives, --

I, an old woman now,

Raking up leaves.

Here in the avenue

Raking up leaves,

Lords' ladies pass in view,

Until one heaves

Sighs at life's russet hue,

Raking up leaves!

Just as my shape you see

Raking up leaves,

I saw, when fresh and free,

Those memory weaves

Into grey ghosts by me,

Raking up leaves.

Yet, Dear, though one may sigh,

Raking up leaves,

New leaves will dance on high --

Earth never grieves! --

Will not, when missed am I

Raking up leaves.

Thomas Hardy, Time's Laughingstocks and Other Verses (Macmillan 1909). Hardy added the subscript "1901" at the bottom of the poem. The date may be put into context by Hardy's comment on the poem in a letter he wrote to a friend in December of 1906: "I happened to be walking, or cycling, through [the park] years ago, when the incident occurred on which the verses are based." (J. O. Bailey, The Poetry of Thomas Hardy: A Handbook and Commentary (University of North Carolina Press 1970), page 207.)

"Earth never grieves!" This is the line that has stayed with me for several decades. Years after having first come across it, I was delighted to discover this passage in a letter written by Philip Larkin to Monica Jones, his long-time companion: "Earth never grieves, I thought, walking across the park, watching seagulls cruising greedily above the ground looking for heaven knows what. Don't you think it's a good line? A very good line." (Philip Larkin, letter to Monica Jones (January 29, 1958), in Philip Larkin, Letters to Monica (edited by Anthony Thwaite) (Faber and Faber 2010), page 235.) I also heartily agree with another comment made by Larkin relating to Hardy (which has appeared here on more than one occasion): "[M]ay I trumpet the assurance that one reader at least would not wish Hardy's Collected Poems a single page shorter, and regards it as many times over the best body of poetic work this century so far has to show?" (Philip Larkin, "Wanted: Good Hardy Critic" (1966), in Philip Larkin, Required Writing: Miscellaneous Pieces 1955-1982 (Faber and Faber 1983), page 174.) Larkin's comment was correct at the time he wrote it in 1966. It remains correct.

[A side-note. Hardy's comment on the source of "Autumn in King's Hintock Park" brings to mind a statement attributed to him in The Life and Work of Thomas Hardy (a biography which was ascribed to his wife, Florence Hardy, when it was first published, but which was actually written mostly by Hardy): "I believe it would be said by people who knew me well that I have a faculty (possibly not uncommon) for burying an emotion in my heart or brain for forty years, and exhuming it at the end of that time as fresh as when interred." (Thomas Hardy and Florence Hardy, The Life and Work of Thomas Hardy (edited by Michael Millgate) (Macmillan 1985), page 408.) These lines from one of Hardy's poems come to mind: "O the regrettings infinite/When the night-processions flit/Through the mind!" (Thomas Hardy, "The Peace-Offering.") We each have our own "regrettings infinite" and flitting "night-processions," don't we?

A poem about Hardy by Siegfried Sassoon, who often visited Hardy at his home in Dorset, provides an evocative glimpse of Hardy and his haunting, ever-present past.

At Max Gate

Old Mr. Hardy, upright in his chair,

Courteous to visiting acquaintance chatted

With unaloof alertness while he patted

The sheep dog whose society he preferred.

He wore an air of never having heard

That there was much that needed putting right.

Hardy, the Wessex wizard, wasn't there.

Good care was taken to keep him out of sight.

Head propped on hand, he sat with me alone,

Silent, the log fire flickering on his face.

Here was the seer whose words the world had known.

Someone had taken Mr. Hardy's place.

Siegfried Sassoon, Collected Poems: 1908-1956 (Faber and Faber 1961). "Max Gate" was the name of Hardy's home in Dorchester. The younger poets of Hardy's time often tended to make their way to Hardy in his later years. For instance, in addition to Sassoon, Walter de la Mare and Edmund Blunden became his friends, and were invited for visits. Like Sassoon, both of them wrote poems about Hardy.]

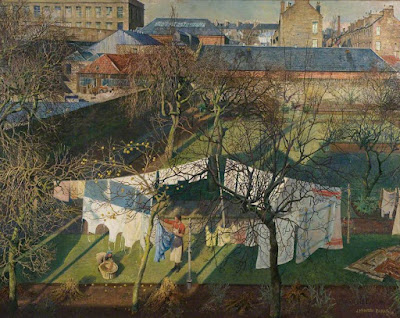

James McIntosh Patrick (1907-1998), "A City Garden" (1940)

"Earth never grieves!" As for us, there is no escape from grief and grieving, is there? This is neither a complaint nor a lament. Grief and grieving are part and parcel of the beauty of the World. What can one do? Continue to pay attention to the beautiful particulars of the World. Above all else, remain grateful.

When I was young, not knowing the taste of grief,

I loved to climb the storied tower,

loved to climb the storied tower,

and in my new songs I'd make it a point to speak of grief.

But now I know all about the taste of grief.

About to speak of it, I stop;

about to speak of it, I stop

and say instead, "Days so cool -- what a lovely autumn!"

Hsin Ch'i-chi (1140-1207) (translated by Burton Watson), in Burton Watson, The Columbia Book of Chinese Poetry: From Early Times to the Thirteenth Century (Columbia University Press 1984), page 371. The poem is untitled.

"Days so cool -- what a lovely autumn!" One can only hope to find the equanimity of Hsin Ch'i-chi. Or the equanimity (and the beauty and truth) of this:

"Are we to look at cherry blossoms only in full bloom, the moon only when it is cloudless? To long for the moon while looking on the rain, to lower the blinds and be unaware of the passing of the spring -- these are even more deeply moving. Branches about to blossom or gardens strewn with faded flowers are worthier of our admiration. Are poems written on such themes as 'Going to view the cherry blossoms only to find they had scattered' or 'On being prevented from visiting the blossoms' inferior to those on 'Seeing the blossoms'? People commonly regret that the cherry blossoms scatter or that the moon sinks in the sky, and this is natural; but only an exceptionally insensitive man would say, 'This branch and that branch have lost their blossoms. There is nothing worth seeing now.'

"In all things, it is the beginnings and ends that are interesting. Does the love between men and women refer only to the moments when they are in each other's arms? The man who grieves over a love affair broken off before it was fulfilled, who bewails empty vows, who spends long autumn nights alone, who lets his thoughts wander to distant skies, who yearns for the past in a dilapidated house -- such a man truly knows what love means."

Kenkō (1283-1350) (translated by Donald Keene), Tsurezuregusa, Chapter 137, in Donald Keene (editor), Essays in Idleness: The Tsurezuregusa of Kenkō (Columbia University Press 1967), pages 115 and 118.

James Paterson (1854-1932), "Moniaive" (1885)

After all my long-windedness, I find myself returning once again to my favorite poem of autumn. (For which I beg the forbearance of long-time -- and much-appreciated! -- readers of this blog.)

Leaves

The prisoners of infinite choice

Have built their house

In a field below the wood

And are at peace.

It is autumn, and dead leaves

On their way to the river

Scratch like birds at the windows

Or tick on the road.

Somewhere there is an afterlife

Of dead leaves,

A stadium filled with an infinite

Rustling and sighing.

Somewhere in the heaven

Of lost futures

The lives we might have led

Have found their own fulfilment

Derek Mahon, The Snow Party (Oxford University Press 1975).

Come to think of it, "Leaves" has something to say about grieving, equanimity, and beauty.

As does this:

The wind has brought

enough fallen leaves

To make a fire.

Ryōkan (translated by John Stevens), in John Stevens, One Robe, One Bowl: The Zen Poetry of Ryōkan (Weatherhill 1977), page 67.

Gilbert Spencer (1892-1979)

"Burdens Farm, with Melbury Beacon" (1943)