I now return, having survived a paucity of beauty and truth over the past two months by reading haiku -- one in the morning and one in the evening -- from R. H. Blyth's four-volume Haiku, and by eventually returning to my walks. I became accustomed to brevity followed by silence. Not a bad thing.

One day earlier this month, I returned to a favorite passage:

"More than half a century of existence has taught me that most of the wrong and folly which darken earth is due to those who cannot possess their souls in quiet; that most of the good which saves mankind from destruction comes of life that is led in thoughtful stillness. Every day the world grows noisier; I, for one, will have no part in that increasing clamour, and, were it only by my silence, I confer a boon on all."

George Gissing, The Private Papers of Henry Ryecroft (Archibald Constable & Co. 1903), pages 13-14.

Of course, this sort of thing (a variation on Pascal) is unrealistic and irresponsible, isn't it? A pernicious daydream, deluded and selfish. And yet . . .

The stillness;

A bird walking on the fallen leaves:

The sound of it.

Ryūshi (d. 1681) (translated by R. H. Blyth), in R. H. Blyth, Haiku, Volume 4: Autumn-Winter (Hokuseido Press 1952), page 365.

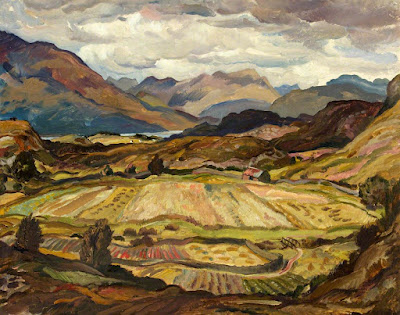

Alexander Sillars Burns (1911-1987), "Afternoon, Wester Ross"

Until a week or so ago, autumn here was unusually sunny and rain-free. The leaves on many of the trees remain green, but they have dried out. The leaf-shadows and sunlight still sway together on the ground, but with less definition, less depth. On a breezy day, the sound overhead has changed: little by little, sibilance has turned to a faint rustling.

Leaves

The prisoners of infinite choice

Have built their house

In a field below the wood

And are at peace.

It is autumn, and dead leaves

On their way to the river

Scratch like birds at the windows

Or tick on the road.

Somewhere there is an afterlife

Of dead leaves,

A stadium filled with an infinite

Rustling and sighing.

Somewhere in the heaven

Of lost futures

The lives we might have led

Have found their own fulfilment.

Derek Mahon, The Snow Party (Oxford University Press 1975).

For me, autumn is not autumn without a visit to Mahon's "Leaves." I return for the poem as a whole, but -- ah! -- the last two lines of the second stanza: the very heart of autumn.

People are few;

A leaf falls here,

Falls there.

Issa (1763-1828) (translated by R. H. Blyth), in R. H. Blyth, Haiku, Volume 4: Autumn-Winter, page 364.

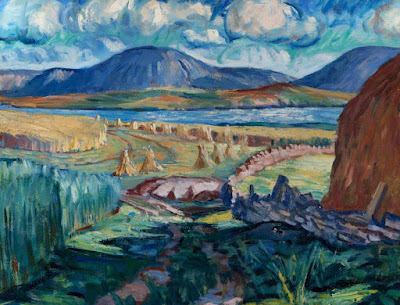

Adam Bruce Thomson (1885-1976), "Harvesting in Galloway"

Every autumn, there is a particular view that I treasure. My usual walking route takes me along the brow of a low hill, about a quarter-mile long. The hill slopes down toward a meadow to the west. As I approach the end of the brow to descend, the highest boughs of three maples that lie in the meadow below appear just beyond the edge of the brow. Their leaves are a brilliant deep-red at this time of year. As I get closer to the edge, the trees are revealed bit-by-bit, from tip to trunk. And, finally, there they are: standing in a serene row as I walk downward toward them.

A Day in Autumn

It will not always be like this,

The air windless, a few last

Leaves adding their decoration

To the trees' shoulders, braiding the cuffs

Of the boughs with gold; a bird preening

In the lawn's mirror. Having looked up

From the day's chores, pause a minute,

Let the mind take its photograph

Of the bright scene, something to wear

Against the heart in the long cold.

R. S. Thomas, Poetry for Supper (Rupert Hart-Davis 1958).

"Life that is led in thoughtful stillness." This is neither indolence nor impassivity.

The wind brings

Enough of fallen leaves

To make a fire.

Ryōkan (1758-1831) (translated by R. H. Blyth), in R. H. Blyth, Haiku, Volume 4: Autumn-Winter, page 357.

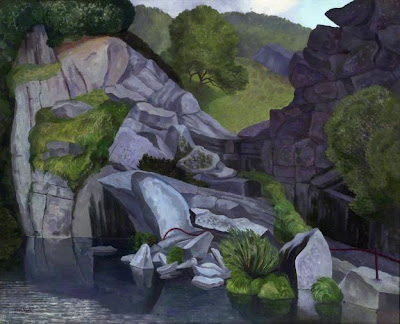

Ian MacInnes (1922-2003), "Harvest, Innertoon" (1959)

As I have said here in the past: this is the season of bittersweet wistfulness and wistful bittersweetness. "You sound like a broken record." This is a phrase that was common in the days of my youth (the Sixties and the Seventies). I'm afraid that it applies to me, a nattering Baby Boomer who looks back on a lost world. Before long, I will be recounting fond memories of neighborhood families raking oak leaves into piles, and setting them ablaze as dusk fell on a Minnesota evening. And, yes, I do remember quite well the smell of burning leaves.

Under Trees

Yellow tunnels under the trees, long avenues

Long as the whole of time:

A single aimless man

Carries a black garden broom.

He is too far to hear him

Wading through the leaves, down autumn

Tunnels, under yellow leaves, long avenues.

Geoffrey Grigson, The Collected Poems of Geoffrey Grigson, 1924-1962 (Phoenix House 1963).

Am I being sentimental about autumn? One sometimes hears derisive comments about "sentimentality." Oh well.

The autumn of my life;

The moon is a flawless moon,

Nevertheless --

Issa (translated by R. H. Blyth), in R. H. Blyth, Haiku, Volume 3: Summer-Autumn (Hokuseido Press 1952), page 396.

Adam Bruce Thomson, "Still Life at a Window" (1944)