On several occasions in his poetry and prose Edward Thomas describes enigmatic meetings with strangers encountered during his walks through the countryside. I use the word "enigmatic" because, although I take it on faith that the strangers actually existed, one also comes away with the feeling that Thomas has encountered a doppelgänger. The strangers are not of the Other World, nor are they menacing. Rather, they carry with them a sense of mystery and melancholy. Which sounds a great deal like Edward Thomas himself.

In his poem "The Other" Thomas never actually meets the stranger. Instead, Thomas inadvertently discovers, through conversations with innkeepers, that someone resembling him has just passed that way. Thomas soon finds himself dogging the stranger's footsteps. The poem is too lengthy (at 110 lines) to post in full. But here is the second stanza:

I learnt his road and, ere they were

Sure I was I, left the dark wood

Behind, kestrel and woodpecker,

The inn in the sun, the happy mood

When first I tasted sunlight there.

I travelled fast, in hopes I should

Outrun that other. What to do

When caught, I planned not. I pursued

To prove the likeness, and, if true,

To watch until myself I knew.

Edward Thomas, in Edna Longley (editor),

Edward Thomas: The Annotated Collected Poems (Bloodaxe Books 2008).

"To watch until myself I knew" is a quintessential piece of studied ambiguity by Thomas. As is: "What to do/When caught, I planned not." Is he the pursuer or the pursued? Or both? (Ambiguity worthy of Robert Frost. But more on him later.)

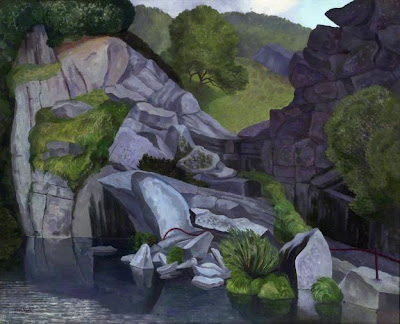

John Nash, "The Lake, Little Horkesley Hall" (c. 1958)

The poem ends with this stanza:

And now I dare not follow after

Too close. I try to keep in sight,

Dreading his frown and worse his laughter.

I steal out of the wood to light;

I see the swift shoot from the rafter

By the inn door: ere I alight

I wait and hear the starlings wheeze

And nibble like ducks: I wait his flight.

He goes: I follow: no release

Until he ceases. Then I also shall cease.

I don't wish to overwork the image, but notice the reference to leaving "the dark wood" in the second stanza, as well as "I steal out of the wood to light" in the final stanza. Dante's

selva oscura comes to mind. But we needn't go that far afield: dark woods are a recurring element in Thomas's poetry. "Out in the dark over the snow/The fallow fawns invisible go." ("

Out in the Dark.") "The Combe was ever dark, ancient and dark." ("The Combe.") "The green roads that end in the forest." ("

The Green Roads.") "Dark is the forest and deep, and overhead/Hang stars like seeds of light/In vain." ("The Dark Forest.")

And, speaking of doppelgängers, dark woods inevitably bring to mind Robert Frost. "One of my wishes is that those dark trees,/So old and firm they scarcely show the breeze,/Were not, as 'twere, the merest mask of gloom,/But stretched away unto the edge of doom." ("Into My Own.") And, of course: "The woods are lovely, dark and deep." ("

Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening.") With each year that passes, my appreciation for the continual conversation between Thomas and Frost (a conversation that did not cease with Thomas's death) grows and grows.

John Nash, "The Barn, Wormingford" (1954)

A few days ago I came across one of these strangers in Thomas's

The Icknield Way. It is evening, and Thomas is walking southwest through the downs beyond Dunstable, Bedfordshire.

"The air was now still and the earth growing dark and already very quiet. But the sky was light and its clouds of utmost whiteness were very wildly and even fiercely shaped, so that it seemed the playground of powerful and wanton spirits knowing nothing of earth. And this dark earth appeared a small though also a kingly and brave place in comparison with the infinite heavens now so joyous and so bright and out of reach. I was glad to be there, but I fell in with a philosopher who seemed to be equally moved yet could not decide whether his condition was to be described as happiness or melancholy. He talked about himself. He was a lean, indefinite man; half his life lay behind him like a corpse, so he said, and half was before him like a ghost. He told me of just such another evening as this and just such another doubt as to whether it was to be put down to the account of happiness or melancholy."

Edward Thomas,

The Icknield Way (1913), page 137.

Thomas then recounts the stranger's story. He had been "digging all day in a heavy soil." Then, at evening, he heard "a woman's voice singing alone somewhere away from where he stood. He forgot who and where he was." The singer "was among the dark trees." The singing went on for a while, then stopped. He heard the sound of "a low laugh drawn out very long an instant afterwards." The woman never appeared.

"He shivered in the cold. The last dead leaves shook upon the beeches, but the silence out there in that world still remained. She was walking or she was in her lover's arms, for aught he knew. No sound came up to him where he stood eager and forlorn until he knew that she must be gone away for ever, like his lyric desires, and he went into his house and it was dark and still and inconceivably empty."

Ibid, pages 142-143.

With that, Thomas concludes the stranger's story. The next sentence brings his encounter with the stranger to an end:

"As I turned into the inn and left him he was inclined either to put down that evening half to happiness and half to melancholy, or to cross out one or other of those headings as being in his case tautological."

Ibid, page 143.

Again, I take it on faith that this stranger who Thomas "fell in with" on the Icknield Way actually existed. But I think that he bears more than a passing resemblance to Thomas. "He was a lean, indefinite man; half his life lay behind him like a corpse, so he said, and half was before him like a ghost." This is Thomas through and through. As is: "he was inclined either to put down that evening half to happiness and half to melancholy, or to cross out one or other of those headings as being in his case tautological." Thomas was never one to be easy on himself.

John Nash, "The Garden" (1951)

The stranger's story of the elusive, mysterious singing woman finds its parallel in a poem by Thomas.

The Unknown

She is most fair,

And when they see her pass

The poets' ladies

Look no more in the glass

But after her.

On a bleak moor

Running under the moon

She lures a poet,

Once proud or happy, soon

Far from his door.

Beside a train,

Because they saw her go,

Or failed to see her,

Travellers and watchers know

Another pain.

The simple lack

Of her is more to me

Than others' presence,

Whether life splendid be

Or utter black.

I have not seen,

I have no news of her;

I can tell only

She is not here, but there

She might have been.

She is to be kissed

Only perhaps by me;

She may be seeking

Me and no other: she

May not exist.

Edward Thomas, in Edna Longley (editor),

Edward Thomas: The Annotated Collected Poems.

This sounds a great deal like the stranger's "lyric desires," doesn't it? Yet Thomas was, if such a thing exists, a realistic romantic. To wit: "this dark earth appeared a small though also a kingly and brave place in comparison with the infinite heavens."

Earlier in

The Icknield Way, Thomas engages in a bantering conversation with another stranger about the possibility of living on the moon. Thomas says: "I should like to try." The stranger responds: "Would you?" Thomas replies: "Yes, provided I were someone different. For, as for me, this is no doubt the best of all possible worlds."

The Icknield Way, page 115. Or, as he says in another poem: "There's nothing like the sun till we are dead." And Frost has something to add here as well: "Earth's the right place for love:/I don't know where it's likely to go better." ("Birches.")

John Nash, "Autumn, Berkshire" (1951)