Speaking of Derek Mahon, I recently realized that I have been remiss: it has been a few years since we last visited my favorite September poem.

September in Great Yarmouth

The woodwind whistles down the shore

Piping the stragglers home; the gulls

Snaffle and bolt their final mouthfuls.

Only the youngsters call for more.

Chimneys breathe and beaches empty,

Everyone queues for the inland cold --

Middle-aged parents growing old

And teenage kids becoming twenty.

Now the first few spots of rain

Spatter the sports page in the gutter.

Council workmen stab the litter.

You have sown and reaped; now sow again.

The band packs in, the banners drop,

The ice-cream stiffens in its cone.

The boatman lifts his megaphone:

'Come in, fifteen, your time is up.'

Derek Mahon, Poems, 1962-1978 (Oxford University Press 1979).

Reginald Brundrit (1883-1960), "The River" (c. 1924)

Late September, and the green leaves still outnumber those that have turned. As the boughs sway in a breeze, one hears a susurration, a sea-sound, not a rattling. On a clear day, leaf-shadows and patches of sunlight continue to revolve on the ground, kaleidoscopic, unceasing.

But yesterday afternoon I noticed dry yellow leaves gathering in the gutters as I walked through what was otherwise a green tunnel of trees. A group of three maples I have come to know as the earliest heralds of autumn began their transformation at the beginning of the month: the highest boughs and the leaves out at the tips of the lower branches are scarlet; only a dwindling inner core of summer green remains. "Now it is September and the web is woven./The web is woven and you have to wear it." (Wallace Stevens, "The Dwarf.")

The Crossing

September, and the butterflies are drifting

Across the sky again, the monarchs in

Their myriads, delicate lenses for the light

To fall through and be mandarin-transformed.

I guess they are flying southward, or anyhow

That seems to be the average of their drift,

Though what you mostly see is a random light

Meandering, a Brownian movement to the wind,

Which is one of Nature's ways of getting it done,

Whatever it may be, the rise of hills

And settling of seas, the fall of leaf

Across the shoulder of the northern world,

The snowflakes one by one that silt the field . . .

All that's preparing now behind the scene,

As the ecliptic and equator cross,

Through which the light butterflies are flying.

Howard Nemerov, Gnomes & Occasions (University of Chicago Press 1973).

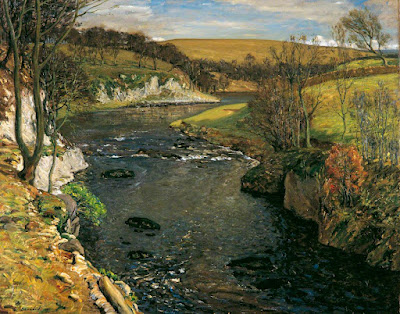

John Lawson (1868-1909), "An Ayrshire Stream" (1893)

I have a vague notion of what occurs when "the ecliptic and equator cross." Something to do with the movement of spheres, I suspect. But I'm reminded of my oft-repeated first principle of poetry: Explanation and explication are the death of poetry. Here is a wider principle I have adopted at this moment: Explanation and explication are the death of enchantment. The enchantment of the World, of course. Mind you, I accept the existence of the ecliptic and the equator. This is not an anti-scientific manifesto. I simply prefer, for instance, a single butterfly or a single leaf, with no explanations attached.

In a headnote to a haiku, Bashō (1644-1694) writes: "As we look calmly, we see everything is content with itself." (Bashō (translated by Makoto Ueda), in Makoto Ueda, Bashō and His Interpreters: Selected Hokku with Commentary (Stanford University Press 1991), page 153.) The haiku is: "Playing in the blossoms/a horsefly . . . don't eat it,/friendly sparrows!" (Bashō (translated by Makoto Ueda), Ibid, page 153.) Ueda provides this annotation: "The headnote is a sentence that often appears in Taoist classics, although Bashō probably took it from a poem by the Confucian philosopher Ch'eng Ming-tao." (Ibid, p. 153.)

Bashō's headnote brings to mind a notebook entry written by Samuel Taylor Coleridge: "September 1 -- the beards of Thistle & dandelions flying above the lonely mountains like life, & I saw them thro' the Trees skimming the lake like Swallows --." (Samuel Taylor Coleridge, in Kathleen Coburn (editor), The Notebooks of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Volume 1: 1794-1804 (Pantheon 1957), Notebook Entry 799 (September 1, 1800). The text is as it appears in the notebook.)

All of which leads us to a single leaf:

Threshold

When in still air and still in summertime

A leaf has had enough of this, it seems

To make up its mind to go; fine as a sage

Its drifting in detachment down the road.

Howard Nemerov, Gnomes & Occasions.

A single leaf. Or a single butterfly. No explanations required, or necessary.

A butterfly flits

All alone -- and on the field,

A shadow in the sunlight.

Bashō (translated by Makoto Ueda), in Makoto Ueda, Matsuo Bashō (Twayne 1970), page 50.

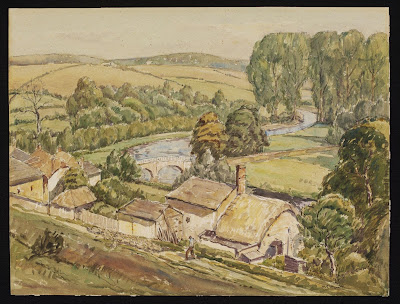

Henry Justice Ford (1860-1941)

"A View of Church Hill from the Mill Pond, Old Swanage" (1931)

[A coda. "The boatman" calling in someone out on the water whose "time is up" in Derek Mahon's "September in Great Yarmouth" makes an appearance in another poem:

Yorkshiremen in Pub Gardens

As they sit there, happily drinking,

their strokes, cancers, and so forth are not in their minds.

Indeed, what earthly good would thinking

about the future (which is Death) do? Each summer finds

beer in their hands in big pint glasses.

And so their leisure passes.

Perhaps the older ones allow some inkling

into their thoughts. Being hauled, as a kid, upstairs to bed

screaming for a teddy or a tinkling

musical box, against their will. Each Joe or Fred

wants longer with the life and lasses.

And so their time passes.

Second childhood; and 'Come in, number 80!'

shouts inexorably the man in charge of the boating pool.

When you're called you must go, matey,

so don't complain, keep it all calm and cool,

there's masses of time yet, masses, masses . . .

And so their life passes.

Gavin Ewart, in Philip Larkin (editor), Poetry Supplement Compiled by Philip Larkin for the Poetry Book Society (Poetry Book Society 1974). Ewart and Larkin were friends. The poem has a Larkinesque feel to it, doesn't it? It's not surprising that Larkin chose to include it in the Poetry Book Society's annual Christmas anthology.

But I like to think that if Larkin had written the poem he would have softened it a bit, and made beautifully clear that we are all Yorkshiremen in pub gardens, each in our own way. He likely would have done so in the final stanza: one long, lovely sentence hedged with one or two qualifications and perhaps containing a reversal -- but absolutely, humanly true. He is not the misanthropic, dour caricature he is often incorrectly made out to be by the inattentive. For example: "Something is pushing them/To the side of their own lives." (Philip Larkin, "Afternoons.") Or: "As they wend away/A voice is heard singing/Of Kitty, or Katy,/As if the name meant once/All love, all beauty." (Philip Larkin, "Dublinesque.") And this: "we should be careful//Of each other, we should be kind/While there is still time." (Philip Larkin, "The Mower.")

For some reason, I find myself reminded of a poem by Su Tung-p'o. It is a poem of spring, and thus may seem out of season. But the final line is apt in any season, and at any time, in any place.

Pear Blossoms by the Eastern Palisade

Pear blossoms pale white, willows deep green --

when willow fluff scatters, falling blossoms will fill the town.

Snowy boughs by the eastern palisade set me pondering --

in a lifetime how many springs do we see?

Su Tung-p'o (1036-1101) (translated by Burton Watson), in Burton Watson, Selected Poems of Su Tung-p'o (Copper Canyon Press 1994), page 68.

In a lifetime, how many Septembers do we see?]

Alexander Jamieson (1873-1937)

"Halton Lake, Wendover, Buckinghamshire"