River Snow

From a thousand hills, bird flights have vanished;

on ten thousand paths, human traces wiped out:

lone boat, an old man in straw cape and hat,

fishing alone in the cold river snow.

Liu Tsung-Yuan (773-819) (translated by Burton Watson), in Burton Watson (editor and translator), The Columbia Book of Chinese Poetry: From Early Times to the Thirteenth Century (Columbia University Press 1984).

There are many things to like about this poem, but I'd like to consider just two of them. First, note the transition from the vast white world of the first two lines ("a thousand hills . . . ten thousand paths") to the single soul alone in the snow of the final two lines. Second, the silent stillness of the scene is palpable and paramount; yet, in the original Chinese text (as well as in Burton Watson's faithful translation) descriptive words such as "silence" or "quiet" or "stillness" do not appear. All is accomplished through implication. Less is more.

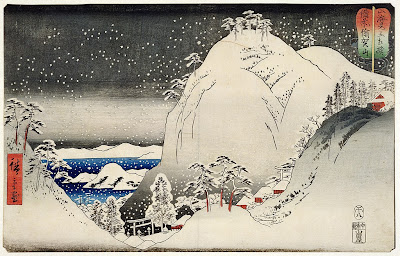

Utagawa Hiroshige (1797-1858), "Bizen Ukazan"

At one point in his writing life, Wallace Stevens was influenced by Chinese poetry. The poem that best reflects this influence is "Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird." The opening and closing sections of the poem are evocatively reminiscent of the atmosphere of "River Snow." Here is Section I in its entirety:

Among twenty snowy mountains,

The only moving thing

Was the eye of the blackbird.

And here is the whole of Section XIII:

It was evening all afternoon.

It was snowing

And it was going to snow.

The blackbird sat

In the cedar-limbs.

Wallace Stevens, Harmonium (1923).

Stevens was too exuberant to employ this sort of style on a regular basis. But these examples demonstrate that he understood quite well the virtues of traditional Chinese poetry. This is particularly true of Section I. In Section XIII, the subjective begins to sneak in: "It was evening all afternoon./It was snowing/And it was going to snow" is classic (and lovely) Stevens, but would seem slightly out of place in a T'ang Dynasty poem, I think.

Utagawa Hiroshige, "Traveller in Snow"

Finally, an untitled poem by Michael Longley seems at home here:

Between now and one week ago when the snow fell, a bird landed

Where they lie, and made cozier and whiter the white patchwork:

And where I imagine her ashes settling on to his collarbone,

The tracks vanish between wing-tips symmetrically printed.

Michael Longley, Gorse Fires (Secker & Warburg 1991).

The poem is the epigraph to Gorse Fires. It follows this dedication: "In Memory Of My Parents."

Utagawa Hiroshige, "Snow Falling on a Town"