I have been visiting Bashō's haiku in December and January. A few weeks before my encounter with the newly-born crescent moon, I came across this:

Unlike anything

it has been compared to:

the third-day moon.

Bashō (1644-1694) (translated by Makoto Ueda), in Makoto Ueda (editor), Bashō and His Interpreters: Selected Hokku with Commentary (Stanford University Press 1991), page 207.

The Japanese phrase for the first phase of the waxing crescent moon is mika no tsuki: "third-day moon." Mika means "third day"; tsuki means "moon"; no is a particle meaning (roughly) "of." Bashō included this headnote to the haiku: "The third day of the month." Ibid. Ueda provides this comment: "Since olden times the crescent moon had been compared to a great many things, including a sickle, a bow, a comb, a boat, and a woman's eyebrow." Ibid. Bashō is absolutely correct: words are not adequate.

As so often happens with poetry, serendipity: a poem appears, and, soon after, the beautiful particulars of the World arrive, echoing it. Or vice versa. In addition, this comes to mind:

Night

That shining moon -- watched by that one faint star:

Sure now am I, beyond the fear of change,

The lovely in life is the familiar,

And only the lovelier for continuing strange.

Walter de la Mare, Memory and Other Poems (Constable 1938).

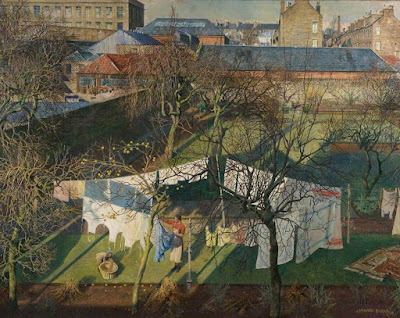

Dudley Holland (1915-1956), "Winter Morning" (1945)

"The lovely in life is the familiar,/And only the lovelier for continuing strange" is paired in my mind with these lines from de la Mare's "Now," which appears in his final collection of poems: "Now is the all-sufficing all/Wherein to love the lovely well,/Whate'er befall." (The italics appear in the original text.) Stumbling across the beauty of the crescent moon early this month brought home the importance of "now": a reproach to my usual state of sleepwalking. And the serene power and charm of that beauty had an element of strangeness to it: the moon seemed impossibly lovely, beyond one's ken.

But there was something else at work as well. The suddenness of that beauty's arrival -- as I absent-mindedly looked skyward -- startled me, took me aback, and leaves me speechless still. Words such as "miraculous" or "revelatory" float to the surface. But I shall restrain myself. Relying on the circumspect William James in his final conclusions on mysticism, I will leave it at this: "higher energies filter in." (William James, The Varieties of Religious Experience: A Study in Human Nature (Longmans, Green and Co. 1902), page 519.)

Best to turn to a poem:

The Elm

This is the place where Dorothea smiled.

I did not know the reason, nor did she.

But there she stood, and turned, and smiled at me:

A sudden glory had bewitched the child.

The corn at harvest, and a single tree.

This is the place where Dorothea smiled.

Hilaire Belloc, Sonnets and Verse (Duckworth 1938).

Belloc's poem, and the phrase "a sudden glory" in particular, bring this to mind:

Sudden Heaven

All was as it had ever been --

The worn familiar book,

The oak beyond the hawthorn seen,

The misty woodland's look:

The starling perched upon the tree

With his long tress of straw --

When suddenly heaven blazed on me,

And suddenly I saw:

Saw all as it would ever be,

In bliss too great to tell;

Forever safe, forever free,

All bright with miracle:

Saw as in heaven the thorn arrayed,

The tree beside the door;

And I must die -- but O my shade

Shall dwell there evermore.

Ruth Pitter (1897-1992), in Don King (editor), Sudden Heaven: The Collected Poems of Ruth Pitter (Kent State University Press 2018), page 106. The poem was written in 1931. Ibid, page 106

Paul Ayshford Methuen (1886-1974)

"Magnolia Soulangiana at Corsham" (c. 1963)

While I was out on my daily walk last week, a few hundred feet in front of me a dark bird with a wide wingspan flew slowly away, just above a grove of pines beside the road. The bird banked to the left, and settled on a branch near the top of a pine. Given the size of the bird's wings, I suspected, and hoped, that it was a bald eagle. But I couldn't be sure from that distance: it could have been a hawk, an owl, or even a large crow. I assumed it would be gone by the time I reached the pine.

But, when I arrived and looked up, there it was: a bald eagle perched on a high branch, surveying the territory. Encountering a bald eagle is not a rare occurrence in this part of the world, but I never cease to be amazed -- and grateful -- when I cross paths with one of them. I never tire of (or get over) those penetrating, unflinching eyes. Or the sharp curve of that deep-yellow beak, unlike any other hue of yellow. Or the cry that now and then comes from the sky as one of them circles slowly overhead.

Arrival

Not conscious

that you have been seeking

suddenly

you come upon it

the village in the Welsh hills

dust free

with no road out

but the one you came in by.

A bird chimes

from a green tree

the hour that is no hour

you know. The river dawdles

to hold a mirror for you

where you may see yourself

as you are, a traveller

with the moon's halo

above him, who has arrived

after long journeying where he

began, catching this

one truth by surprise

that there is everything to look forward to.

R. S. Thomas, Later Poems (Macmillan 1983).

R. S. Thomas' poems can be spare and acerbic, especially when his subject is the modern world. But there is no shortage of beauty. The heart of his poetry is his lifelong attendance upon the silence of God, as he makes his way through our short time in Paradise (Wales, in Thomas' case). At times there is a note of complaint, the merest hint of a doubt. But withal he is patient. He is often rewarded.

The Bright Field

I have seen the sun break through

to illuminate a small field

for a while, and gone my way

and forgotten it. But that was the pearl

of great price, the one field that had

the treasure in it. I realize now

that I must give all that I have

to possess it. Life is not hurrying

on to a receding future, nor hankering after

an imagined past. It is the turning

aside like Moses to the miracle

of the lit bush, to a brightness

that seemed as transitory as your youth

once, but is the eternity that awaits you.

R. S. Thomas, Laboratories of the Spirit (Macmillan 1975).

Ian Grant (1904-1993), "Cheshire Mill" (1939)

The beautiful particulars of the World often arrive unexpectedly and unaccountably at our doorstep, or we at theirs. Suddenly. There is no planning involved, nor itinerary to be followed. We simply need to pay attention. (So says an inveterate sleepwalker.) And never cease to be grateful.

To a mountain village

at nightfall on a spring day

I came and saw this:

blossoms scattering on echoes

from the vespers bell.

Nōin (988-1050) (translated by Steven Carter), in Steven Carter (editor), Traditional Japanese Poetry: An Anthology (Stanford University Press 1991), page 134.

James Cowie (1886-1956), "Pastoral" (c. 1938)