For instance, this past week I discovered the following poem. How had I missed it all these years?

The Sun's Last Look on the Country Girl

(M. H.)

The sun threw down a radiant spot

On the face in the winding-sheet --

The face it had lit when a babe's in its cot;

And the sun knew not, and the face knew not,

That soon they would no more meet.

Now that the grave has shut its door,

And lets not in one ray,

Do they wonder that they meet no more --

That face and its beaming visitor --

That met so many a day?

Thomas Hardy, Late Lyrics and Earlier, with Many Other Verses (Macmillan 1922).

"M. H." refers to Mary Hardy, Hardy's sister, who died in November of 1915. The poem was written in December of that year. Ten years later, Hardy made the following journal entry: "December 23. Mary's birthday. She came into the world . . . and went out . . . and the world is just [the] same . . . not a ripple on the surface left." Thomas Hardy, The Life and Work of Thomas Hardy (edited by Michael Millgate) (Macmillan 1985), page 464 (ellipses in original).

How like Hardy to notice such a detail and then turn it into something so affecting. Who but Hardy would have thought to create the lovely relationship between the country girl and the sun? Too sentimental? Of course not. Here is a test: please read the poem again, and, as you do so, think of someone you have loved who has passed away.

"Such, then, is the tenderness of Thomas Hardy. I do not know any other English poet who strikes that note of tenderness so firmly and so resonantly. You must forgive me for using what is called 'emotive language' about his work: but, when one is deeply touched by a poem, I can see no adequate reason for concealing the fact.

* * * * *

Great poems have been written by immature, flawed, or unbalanced men; but not, I suggest, great personal poetry; for this, ripeness, breadth of mind, charity, honesty are required: that is why great personal poetry is so rare. It is an exacting medium -- one that will not permit us to feign notable images of virtue. False humility, egotism, or emotional insincerity cannot be hidden in such poetry: they disintegrate the poem. Thomas Hardy's best poems do seem to me to offer us images of virtue; not because he moralises, but because they breathe out the truth and goodness that were in him, inclining our own hearts towards what is lovable in humanity."

C. Day Lewis, The Lyrical Poetry of Thomas Hardy: The Wharton Lecture on English Poetry (The British Academy 1951) (italics in original).

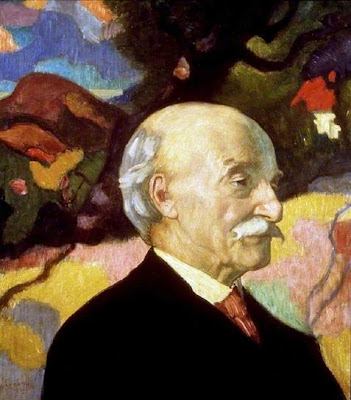

William Anstice Brown, "In Purley Meadow, Sherborne, Dorset" (1979)

Day Lewis's use of the word "feign" in the preceding passage reminds me of a wonderful observation by Edward Thomas on the nature of poetry (an observation that has appeared here on more than one occasion): "if what poets say is true and not feigning, then of how little account are our ordinary assumptions, our feigned interests, our playful and our serious pastimes spread out between birth and death." Edward Thomas, Feminine Influence on the Poets (Martin Secker 1910), page 86.

The phrase "true and not feigning" perfectly describes Thomas Hardy's poetry as a whole, both the well-known old chestnuts ("During Wind and Rain," "The Darkling Thrush," "The Convergence of the Twain," "In Time of 'The Breaking of Nations'," "The Oxen," for instance) and the lesser-known, out-of-the-way poems that often go unnoticed. I believe that, in order to appreciate the truth, beauty, compassion, and charm of Hardy's poetry, one needs to become acquainted with the smaller hidden treasures.

Just the Same

I sat. It all was past;

Hope never would hail again;

Fair days had ceased at a blast,

The world was a darkened den.

The beauty and dream were gone,

And the halo in which I had hied

So gaily gallantly on

Had suffered blot and died!

I went forth, heedless whither,

In a cloud too black for name:

-- People frisked hither and thither;

The world was just the same.

Thomas Hardy, Late Lyrics and Earlier, with Many Other Verses.

"Because he was haunted by Time and transience, because he never saw the commonest thing without a vision of what it once had been, of what it one day would be, in return even the commonest things were lit for him with a gleam of tragic poetry. He saw things as instinctively in three tenses as in three dimensions. In this way he widened the domain of poetry till it became for him as wide as life itself, a life intensely sad and yet intensely real. The comfort that religion failed to give, he found and thought that others might find, not necessarily in writing poetry about this world, but in seeing this world poetically, as anyone with an imagination can. . . . Hardy did not simply make poetry out of life; he made life into poetry.

* * * * *

He deliberately took for his subjects the commonest and most natural feelings; but by an unfamiliar side, and with that insight which only sensitiveness and sympathy can possess. This sympathy is important; for, as I have said, if truthfulness is one main feature of Hardy's work, its compassion is another."

F. L. Lucas, Ten Victorian Poets (Cambridge University Press 1940).

Henry Justice Ford (1860-1941)

"A View of Church Hill from the Mill Pond, Old Swanage, Dorset" (1931)

Ah, the things we see in this world! Sights that cause us to catch our breath, and that return to haunt us at unexpected times. Speaking for myself, I can testify to the urge to look away in order to avoid future hauntings. Thomas Hardy never averted his eyes.

At a Country Fair

At a bygone Western country fair

I saw a giant led by a dwarf

With a red string like a long thin scarf;

How much he was the stronger there

The giant seemed unaware.

And then I saw that the giant was blind,

And the dwarf a shrewd-eyed little thing;

The giant, mild, timid, obeyed the string

As if he had no independent mind,

Or will of any kind.

Wherever the dwarf decided to go

At his heels the other trotted meekly,

(Perhaps -- I know not -- reproaching weakly)

Like one Fate bade that it must be so,

Whether he wished or no.

Various sights in various climes

I have seen, and more I may see yet,

But that sight never shall I forget,

And have thought it the sorriest of pantomimes,

If once, a hundred times!

Thomas Hardy, Moments of Vision and Miscellaneous Verses (Macmillan 1917).

What are we to make of this poem? Is it merely another example of Hardy the purported pessimist? No, this is simply Hardy doing what he always does: reporting what he sees. What is the poem "about"? Long-time readers of this blog will know my response: explanation and explication are the death of poetry.

The most you will get from me is this: the poem is about seeing a sight that forever haunts you. Does such an experience change the world? No. Why should it? Does such an experience change your soul? We each have to answer that question for ourselves.

Eric Bray, "Allington, Dorset, from Victoria Grove" (1975)

The following passage by David Cecil articulates far better than I can what draws me to Hardy. Cecil's remarks about Hardy are remarkably similar to those of C. Day Lewis and F. L. Lucas. They all have their source, I think, in a great love for the man.

"His poems bear the recognisible stamp of his personality, simple, sublime, lovable. Here we come to the central secret of the spell he casts. It compels us because it brings us into immediate contact with a spirit that commands our hearts as well as our admiration. It combines a special charm, a special nobility. The charm unites unexpectedly the naïve and the sensitive. Hardy addresses us directly, unreservedly, unselfconsciously; yet he is not unsubtle or imperceptive. On the contrary he shows himself exquisitely appreciative of delicate shades of feeling and of fleeting nuances of beauty. Similarly his nobility of nature fuses tenderness and integrity. His integrity is absolute. He faces life at its darkest, he is vigilant never to soften or to sentimentalise; yet he never strikes a note of hardness or brutality. His courage in facing hard facts is equalled by his capacity to pity and sympathise."

David Cecil, "The Hardy Mood," in F. B. Pinion (editor), Thomas Hardy and the Modern World (Thomas Hardy Society 1974).

Thomas Hardy is a human being (a lovable, sensitive, compassionate human being) speaking directly and without guile to other human beings. He is unfailingly honest. This means that the truths he tells you will be both beautiful and harrowing by turns (or at the same time). But he will never lie to you. He knows that we are all in this together. And he knows that our time is short.

The Comet at Yalbury or Yell'ham

I

It bends far over Yell'ham Plain,

And we, from Yell'ham Height,

Stand and regard its fiery train,

So soon to swim from sight.

II

It will return long years hence, when

As now its strange swift shine

Will fall on Yell'ham; but not then

On face of mine or thine.

Thomas Hardy, Poems of the Past and the Present (Macmillan 1901).

"May. In an orchard at Closeworth. Cowslips under trees. A light proceeds from them, as from Chinese lanterns or glow-worms."

Thomas Hardy, journal entry for May, 1876, in Thomas Hardy, The Life and Work of Thomas Hardy (edited by Michael Millgate) (Macmillan 1985), page 112.

Alfred Egerton Cooper (1883-1974), "Dorset Landscape"