The conversation repeated itself in the same fashion as I walked on. "Hoo-hoo . . . hoo-hoo." Brief silence. "Caw-caw-caw." Quite civilized, I concluded. The exchange had not come to an end as I passed out of earshot. I had developed a fondness for both of them. For their part, they were likely unaware of my existence. I take no offense at this. The three of us were just passing through the World on an afternoon near the end of winter. We crossed paths and continued on our separate ways. But I now think of the title of a poem by Robert Frost: "For Once, Then, Something."

Crofter

Last thing at night

he steps outside to breathe

the smell of winter.

The stars, so shy in summer,

glare down

from a huge emptiness.

In a huge silence he listens

for small sounds. His eyes

are filled with friendliness.

What's history to him?

He's an emblem of it

in its pure state.

And proves it. He goes inside.

The door closes and the light

dies in the window.

Norman MacCaig, The Poems of Norman MacCaig (edited by Ewen McCaig) (Polygon 2005), page 452.

MacCaig's "Crofter" always brings to mind this:

The Shepherd's Hut

Now when I could not find the road

Unless beside it also flowed

This cobbled beck that through the night,

Breaking on stones, makes its own light,

Where blackness in the starlit sky

Is all I know a mountain by,

A shepherd little thinks how far

His lamp is shining like a star.

Andrew Young, The Poetical Works of Andrew Young (edited by Edward Lowbury and Alison Young) (Secker & Warburg 1985), page 65.

John Nash (1893-1977), "Dorset Landscape" (c. 1930)

My daily walk takes me through the grounds of what was once a post of the United States Army, an important embarkation point for troops bound for the Pacific during the Second World War. The post has long since been converted into a city park. But a number of large wooden buildings constructed early in the last century have been preserved. They have been painted a pleasing pale yellow, with white trim on the windows, doors, and eaves. They stand here and there amidst the meadows and trees, beside the wide concrete paths that wind through the grounds of the former post.

On a sunny day this week, as I walked through a budding grove of trees, a distant yet clear solo saxophone rendition of "The Girl from Ipanema" wafted through the air. I knew the source: over the past few months, a lone saxophonist has been practicing on the front porch of one of the buildings, which is set back on a lawn, surrounded by big-leaf maple trees. This was the first time I had heard him play a song all the way through.

The Just

A man who cultivates his garden, as Voltaire wished.

He who is grateful for the existence of music.

He who takes pleasure in tracing an etymology.

Two workmen playing, in a café in the South, a silent game of chess.

The potter, contemplating a color and a form.

The typographer who sets this page well, though it may not please him.

A woman and a man, who read the last tercets of a certain canto.

He who strokes a sleeping animal.

He who justifies, or wishes to, a wrong done him.

He who is grateful for the existence of Stevenson.

He who prefers others to be right.

These people, unaware, are saving the world.

Jorge Luis Borges (translated by Alastair Reid), in Jorge Luis Borges, Selected Poems (edited by Alexander Coleman) (Viking 1999), page 449.

"The Girl from Ipanema." A fine choice of music by the saxophonist. I was alive when the song became a hit in this country in 1964. Sixty years ago. Imagine that. At this point, as a member of the Baby Boom Generation, I feel compelled to observe that, when it comes to music, I lived through a charmed time. Or am I being "sentimental"? (A state of being which some sophisticated moderns find unacceptable. I've often wondered why this is so.)

But I did not engage in this internal back-and-forth as "The Girl from Ipanema" arrived unexpectedly on the breeze, passing through the warm sunlight and the boughs of the trees on its way, a few days before the beginning of Spring. I simply received a wonderful gift.

Shinto

When sorrow lays us low

for a second we are saved

by humble windfalls

of mindfulness or memory:

the taste of a fruit, the taste of water,

that face given back to us by a dream,

the first jasmine of November,

the endless yearning of the compass,

a book we thought was lost,

the throb of a hexameter,

the slight key that opens a house to us,

the smell of a library, or of sandalwood,

the former name of a street,

the colors of a map,

an unforeseen etymology,

the smoothness of a filed fingernail,

the date we were looking for,

the twelve dark bell-strokes, tolling as we count,

a sudden physical pain.

Eight million Shinto deities

travel secretly throughout the earth.

Those modest gods touch us --

touch us and move on.

Jorge Luis Borges (translated by Hoyt Rogers), Ibid, page 451.

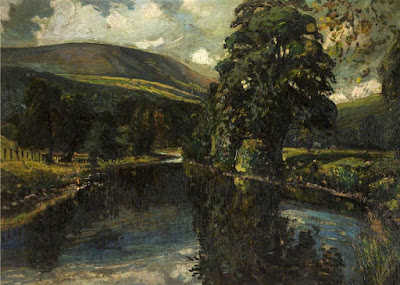

John Nash, "The Lake, Little Horkesley Hall" (c. 1958)

A conversation between an owl and a crow. A song from sixty years ago, borne on the wind. As I have often said here in the past: in this World in which our time is short, we should pay attention and, above all, be grateful.

Message Taken

On a day of almost no wind,

today,

I saw two leaves falling almost, not quite,

perpendicularly -- which

seemed natural.

When I got closer, I saw

the leaves on the tree were

slanted by that wind, were pointing

towards those that had fallen.

When I got closer than that, I saw

the leaves on the tree

were trembling.

And that seemed natural too.

Norman MacCaig, The Poems of Norman MacCaig, page 245.

John Nash, "The Barn, Wormingford" (1954)