On the other hand, however, Hardy seems very close to us. He died less than a 100 years ago -- in 1928, which doesn't seem so far away. The living veterans of World War II were born before Hardy's death. And think of this: Philip Larkin was six-years-old when Hardy died.

Now, that is a wonderful piece of poetic continuity: the lives of William Wordsworth and Thomas Hardy and Philip Larkin overlapped one another.

John Everett, "Maumbury Rings, Dorchester, Dorset" (1924)

Birthday Poem for Thomas Hardy

Is it birthday weather for you, dear soul?

Is it fine your way,

With tall moon-daisies alight, and the mole

Busy, and elegant hares at play

By meadow paths where once you would stroll

In the flush of day?

I fancy the beasts and flowers there beguiled

By a visitation

That casts no shadow, a friend whose mild

Inquisitive glance lights with compassion,

Beyond the tomb, on all of this wild

And humbled creation.

It's hard to believe a spirit could die

Of such generous glow,

Or to doubt that somewhere a bird-sharp eye

Still broods on the capers of men below,

A stern voice asks the Immortals why

They should plague us so.

Dear poet, wherever you are, I greet you.

Much irony, wrong,

Innocence you'd find here to tease or entreat you,

And many the fate-fires have tempered strong,

But none that in ripeness of soul could meet you

Or magic of song.

Great brow, frail frame -- gone. Yet you abide

In the shadow and sheen,

All the mellowing traits of a countryside

That nursed your tragi-comical scene;

And in us, warmer-hearted and brisker-eyed

Since you have been.

C. Day Lewis, Poems 1943-1947 (1948).

Day Lewis's reference to Hardy's "bird-sharp eye" brings to mind Llewellyn Powys's memory of meeting Hardy in 1919: "He came in at last, a little old man (dressed in tweeds after the manner of a country squire) with the same round skull and the same goblin eyebrows and the same eyes keen and alert. What was it that he reminded me of? A night hawk? a falcon owl? for I tell you the eyes that looked out of that century-old skull were of the kind that see in the dark." Edmund Blunden, Thomas Hardy (1941), page 159. For those who may be interested, in previous posts I have mentioned the observations of Powys, H. M. Tomlinson, Blunden, and Siegfried Sassoon upon meeting Hardy in his late years.

John Everett, "Near Corfe Heath, Dorset" (1924)

Waiting Both

A star looks down at me,

And says: 'Here I and you

Stand, each in our degree:

What do you mean to do, --

Mean to do?'

I say: 'For all I know,

Wait, and let Time go by,

Till my change come.' -- 'Just so,'

The star says: 'So mean I: --

So mean I.'

Thomas Hardy, Human Shows, Far Phantasies, Songs and Trifles (1925).

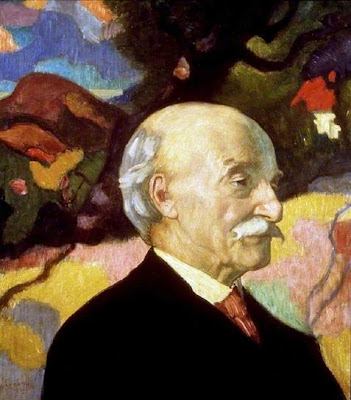

William Strang, "Thomas Hardy" (1920)