April is the cruellest month, breeding

Lilacs out of the dead land, mixing

Memory and desire, stirring

Dull roots with spring rain.

T. S. Eliot, The Waste Land (Boni and Liveright 1922).

I seem to recall that the presence of April, my birth month, played some role in why I was smitten with the lines. But I could be misremembering. On the other hand, I was a melancholy, bookish lad (some things never change), so I suspect my recollection may be accurate. In any case, the lines have remained with me for nearly fifty years, even though my affections have long since migrated from The Waste Land to Four Quartets.

All of which leads (in a roundabout fashion), dear ever-patient readers, to our annual visit to my favorite April poem:

Wet Evening in April

The birds sang in the wet trees

And as I listened to them it was a hundred years from now

And I was dead and someone else was listening to them.

But I was glad I had recorded for him the melancholy.

Patrick Kavanagh, Collected Poems (edited by Antoinette Quinn) (Penguin 2004). The poem was originally published on April 19, 1952, in Kavanagh's Weekly. Ibid, page 280.

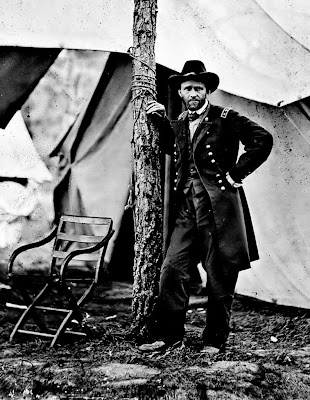

Allan Gwynne-Jones (1892-1982), "Spring Evening, Froxfield"

I suppose one might argue that "Wet Evening in April" is not a true "April poem" at all. One expects something along these lines: "Loveliest of trees, the cherry now/Is hung with bloom along the bough . . ." Or something even more effulgent and, yes, flowery:

April, 1885

Wanton with long delay the gay spring leaping cometh;

The blackthorn starreth now his bough on the eve of May:

All day in the sweet box-tree the bee for pleasure hummeth:

The cuckoo sends afloat his note on the air all day.

Now dewy nights again and rain in gentle shower

At root of tree and flower have quenched the winter's drouth.

On high the hot sun smiles, and banks of cloud uptower

In bulging heads that crowd for miles the dazzling south.

Robert Bridges, The Shorter Poems (George Bell & Sons 1890). Caught up in his enthusiasm for the month, Bridges includes sprightly internal rhymes within the first five lines.

Or perhaps something more restrained, but still evocative of the month's beautiful and hopeful course:

April

Exactly: where the winter was

The spring has come: I see her now

In the fields, and as she goes

The flowers spring, nobody knows how.

C. H. Sisson, What and Who (Carcanet Press 1994).

Mind you, I am quite fond of each of these poems, and they have appeared here on more than one occasion. Still, April would not be April without its characteristic tinge of melancholy. All of those cherry, plum, and pear petals drifting down beneath a blue sky, carpeting the green grass and the sidewalks. It's wonderful how April and October share a similar bittersweet wistfulness and wistful bittersweetness, isn't it? Every six months, year after year, the falling of petals and the falling of leaves. Trying to tell us something.

William Wood (1877-1958), "April Weather"

Ah, well, everything in the World and in our life eventually comes around to our evanescence, and the evanescence of the beautiful particulars that surround us. "But it is a sort of April weather life that we lead in this world. A little sunshine is generally the prelude to a storm." (William Cowper, letter to Walter Bagot (January 3, 1787), in James King and Charles Ryskamp (editors), The Letters and Prose Writings of William Cowper, Volume III: Letters 1787-1791 (Oxford University Press 1982), pages 5-6.) This is lovely, but perhaps too dramatic. Life is a matter of petals and of leaves. And of gratitude.

Pear Blossoms by the Eastern Palisade

Pear blossoms pale white, willows deep green —

when willow fluff scatters, falling blossoms will fill the town.

Snowy boughs by the eastern palisade set me pondering —

in a lifetime how many springs do we see?

Su Tung-p'o (1036-1101) (translated by Burton Watson), in Burton Watson, Selected Poems of Su Tung-p'o (Copper Canyon Press 1994), page 68.

Adrian Paul Allinson (1890-1959), "The Cornish April"