Over the course of their careers, it was the lot of most poet-civil servants to be suddenly and unexpectedly relocated by the government to obscure cities and provinces in the hinterlands. This was generally due to standard bureaucratic practice: periodic relocations prevented the accumulation of influence and power. Alternatively (and not uncommonly), the relocation was due to the imposition of exile as a punishment for running afoul of the ruling clique -- perhaps by writing a poem containing a too thinly veiled criticism of the clique. Either way, the life of a poet in governmental service was one of departures and separations.

As but one example, here is one of the best-known, and most admired, poems of farewell:

Seeing a Friend Off

Green hills sloping from the northern wall,

white water rounding the eastern city:

once parted from this place

the lone weed tumbles ten thousand miles.

Drifting clouds -- a traveler's thoughts;

setting sun -- an old friend's heart.

Wave hands and let us take leave now,

hsiao-hsiao our hesitant horses neighing.

Li Po (701-762) (translated by Burton Watson), in Burton Watson, The Columbia Book of Chinese Poetry: From Early Times to the Thirteenth Century (Columbia University Press 1984), page 212.

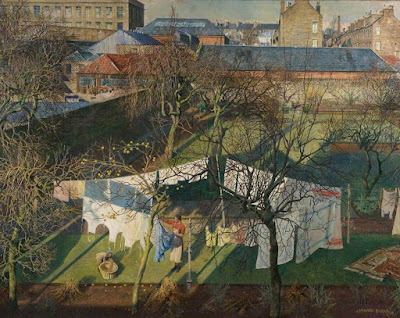

George Vicat Cole (1833-1893), "Autumn Morning" (1891)

As is the case with "Seeing a Friend Off," the poems of parting and separation are often affecting and lovely: the sense of loss and sorrow is genuine, and is much more than a matter of poetic convention. Moreover, there is a wider context for the parting and separation, for the loss and sorrow.

Dreaming that I Went with Li and Yü to Visit Yüan Chen

At night I dreamt I was back in Ch'ang-an;

I saw again the faces of old friends.

And in my dreams, under an April sky,

They led me by the hand to wander in the spring winds.

Together we came to the ward of Peace and Quiet;

We stopped our horses at the gate of Yüan Chen.

Yüan Chen was sitting all alone;

When he saw me coming, a smile came to his face.

He pointed back at the flowers in the western court;

Then opened wine in the northern summer-house.

He seemed to be saying that neither of us had changed;

He seemed to be regretting that joy will not stay;

That our souls had met only for a little while,

To part again with hardly time for greeting.

I woke up and thought him still at my side;

I put out my hand; there was nothing there at all.

Po Chü-i (772-846) (translated by Arthur Waley), in Arthur Waley, More Translations from the Chinese (George Allen & Unwin 1919), page 46. According to a note by Waley, the poem was "written in exile." Arthur Waley, Chinese Poems (George Allen & Unwin 1946), page 159.

The phrase "a continual farewell" returned to me when I read Po Chü-i's poem a few days ago. It appears in the closing lines of W. B. Yeats' poem "Ephemera": "Before us lies eternity; our souls/Are love, and a continual farewell." "Ephemera" is an autumnal poem ("the yellow leaves/Fell like faint meteors in the gloom") about the pain of the loss of youthful love, written during Yeats' fin de siècle Celtic Twilight period. It has nothing to do with Chinese poetry. Yet I think the two lines -- and particularly the beautiful "a continual farewell" -- tell us something about why poems written centuries ago by poet-civil servants in another land continue to speak to us so movingly about our life and fate.

John Haswell (1855-1925), "Whitnash Church"

Yüan Chen (779-831) was Po Chü-i's dearest friend. After passing their civil service examinations, they spent their younger years together while serving in governmental positions in Ch'ang-an, which was the capital of China at that time. Over the course of more than three decades, Po Chü-i wrote a number of poems about their separations, which were occasioned by their periodic reassignments and banishments. This, for instance, is one of the most beloved poems in Chinese literature:

On Board Ship: Reading Yüan Chen's Poems

I take your poems in my hand and read them beside the candle;

The poems are finished, the candle is low, dawn not yet come.

My eyes smart; I put out the lamp and go on sitting in the dark,

Listening to waves that, driven by the wind, strike the prow of the ship.

Po Chü-i (translated by Arthur Waley), in Arthur Waley, One Hundred and Seventy Chinese Poems (Constable 1918), page 142.

Yüan Chen died at the young age (even for those times) of 52. Nine years after Yüan Chen's death, Po Chü-i, at the age of 68, wrote this:

On Hearing Someone Sing a Poem by Yüan Chen

No new poems his brush will trace;

Even his fame is dead.

His old poems are deep in dust

At the bottom of boxes and cupboards.

Once lately, when someone was singing,

Suddenly I heard a verse --

Before I had time to catch the words

A pain had stabbed my heart.

Po Chü-i (translated by Arthur Waley), in Arthur Waley, Ibid, page 165.

Po Chü-i does not identify which poem of Yüan Chen's he heard being sung. But, who knows, perhaps it was this, written by Yüan Chen after the death of his wife:

Bamboo Mat

I cannot bear to put away

the bamboo sleeping mat --

that first night I brought you home,

I watched you roll it out.

Yüan Chen (translated by Sam Hamill), in Sam Hamill, Crossing the Yellow River: Three Hundred Poems from the Chinese (BOA Editions 2000), page 191.

Henry Morley (1869-1937), "Lifting Potatoes near Stirling"

Among poetry's many wonders, perhaps the most wondrous is the echoing and reaffirmation of Beauty and Truth throughout the ages and in all corners of the World. Every poet writes his or her poems in times which are parlous, full of clamorous madness, and beset with evil, ill-will, duplicity, and bad faith. Yet through it all runs the serene thread of Beauty and Truth. "Together we came to the ward of Peace and Quiet." (Thank you, Po Chü-i and Arthur Waley.)

In the Ninth Century, during the T'ang Dynasty (the greatest period of Chinese poetry), Po Chü-i wrote this about his dream of Yüan Chen:

He seemed to be saying that neither of us had changed;

He seemed to be regretting that joy will not stay;

That our souls had met only for a little while,

To part again with hardly time for greeting.

In Japan, approximately ten centuries later, Ryōkan wrote this:

We meet only to part,

Coming and going like white clouds,

Leaving traces so faint

Hardly a soul notices.

Ryōkan (1758-1831) (translated by John Stevens), in John Stevens, Dewdrops on a Lotus Leaf: Zen Poems of Ryōkan (Shambhala 1996), page 91.

Ryōkan was a Zen Buddhist monk who elected to live a life of penury in a mountain hut. He was well-educated, and had studied Chinese philosophy and literature. Chinese poetry had long been admired by Japanese waka and haiku poets, and Po Chü-i was a particular favorite of many of those poets. It is not unlikely that Ryōkan was familiar with Po Chü-i's poetry. Had he read "Dreaming that I Went with Li and Yü to Visit Yüan Chen"? We have no way of knowing. It would be lovely to discover that Ryōkan did indeed have Po Chü-i's four lines in mind when he wrote his own poem. But it is also wonderful to think that two human beings -- in different lands and at different times -- recognized, and articulated in a beautiful fashion, a fundamental truth about what it means to live in the World.

And, nearly a century later in Ireland, W. B. Yeats wrote this:

Before us lies eternity; our souls

Are love, and a continual farewell.

W. B. Yeats, "Ephemera," Poems (T. Fisher Unwin 1895).

The thread is continuous and consistent, and remains unbroken: souls; partings; a continual farewell.

For me, who go,

for you who stay behind --

two autumns.

Masaoka Shiki (1867-1902) (translated by Burton Watson), in Masaoka Shiki, Selected Poems (edited by Burton Watson) (Columbia University Press 1997), page 44.

Alfred Parsons (1847-1920), "Meadows by the Avon"