As I have mentioned here in the past, each day I read a poem in the morning and a poem in the evening. This was today's morning poem:

Autumn Ends

Lost in vacant wonder at how the months flow away in silence,

I sit alone in my idle hut, thinking endless thoughts.

An old man's cares, like these leaves, are hard to sweep away.

To the sound of their rustling I see autumn off once again.

Tate Ryūwan (1762-1844) (translated by Burton Watson), in Burton Watson (editor), Kanshi: The Poetry of Ishikawa Jōzan and Other Edo-Period Poets (North Point Press 1990), page 117. A kanshi (a Japanese word meaning "Chinese poem") is a poem written in Chinese by a Japanese poet, following the strict rules of Chinese prosody. (For a discussion of kanshi, please see my post of November 2, 2014.)

I have read "Autumn Ends" several times in the past, but I hadn't revisited it recently. This morning, I came upon it while browsing through Watson's anthology, which is one of my favorite books. After reading the poem, it occurred to me: isn't today the day of the winter solstice, or was it yesterday, or is it tomorrow? I checked: it is indeed today. Reading poetry tends to put one in the way of serendipity.

But, beyond this nice bit of happenstance, I realized that, with each passing year, "Autumn Ends" seems more and more apt. Something along these lines: "In a lifetime, how many springs do we see?" (Su Tung-p'o (1036-1101) (translated by Burton Watson), "Pear Blossoms by the Eastern Palisade.") Or this: "the years just flow by like a broken-down dam." (John Prine, "Angel from Montgomery.") Ah, well, no help for it.

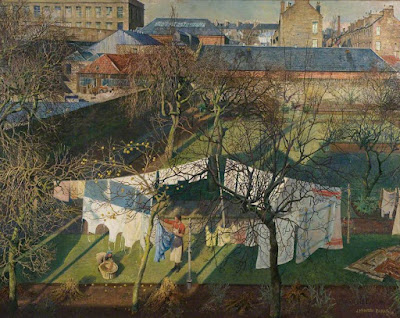

John Milne Donald (1819-1866), "Autumn Leaves" (1864)

As I am wont to say: "In poetry, one thing leads to another." Thus, not surprisingly, my favorite autumn poem came to mind soon after I read "Autumn Ends" this morning. The poem usually appears here each autumn, but this year it makes its appearance on the first day of winter.

Leaves

The prisoners of infinite choice

Have built their house

In a field below the wood

And are at peace.

It is autumn, and dead leaves

On their way to the river

Scratch like birds at the windows

Or tick on the road.

Somewhere there is an afterlife

Of dead leaves,

A stadium filled with an infinite

Rustling and sighing.

Somewhere in the heaven

Of lost futures

The lives we might have led

Have found their own fulfilment.

Derek Mahon, The Snow Party (Oxford University Press 1975), page 3.

It is lovely to find "rustling" leaves in both "Autumn Ends" and "Leaves." It is those rustling leaves that follow us on our autumn walks -- dogging our footsteps -- that capture the heart of autumn. And Mahon takes things a beautiful step further: "It is autumn, and dead leaves/On their way to the river/Scratch like birds at the windows/Or tick on the road."

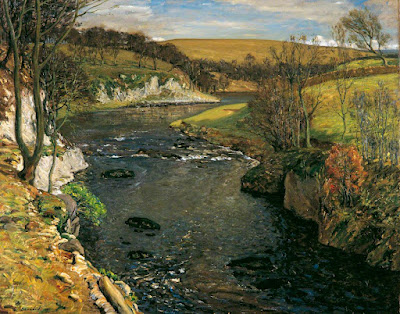

George Vicat Cole (1833-1893), "Autumn Morning" (1891)

Today I went for my daily late afternoon walk, both poems still on my mind. After intermittent rain, often heavy, in the morning, the sky overhead and to the west was clearing: a mix of blue, gold, pink, and orange. The sun was on its way to disappearing beyond the waters of Puget Sound, beyond the Olympic Mountains, off into the Pacific. Not a bad way to bring autumn to a close, to enter winter.

The ground remains strewn with all of those rustling leaves. But the sparrows, our companions throughout the winter, were lively, sporting in the remaining sunlight. Of course, they know what the fallen rustling leaves are telling us. But they go on being their sparrow selves.

After seeing them twittering and flitting in the bushes and on the green meadow grass, I thought of this:

The Bamboo Sparrow

Doesn't peck up millet from the government storehouse,

Doesn't bore holes through the master's house;

It dwells a lifetime in the mountain groves

And roosts at nightfall on a branch of bamboo.

Gido Shūshin (1325-1388) (translated by Marian Ury), in Marian Ury (editor), Poems of the Five Mountains: An Introduction to the Literature of the Zen Monasteries (Center for Japanese Studies, The University of Michigan 1992), page 68. "The Bamboo Sparrow," like "Autumn Ends," is a kanshi.

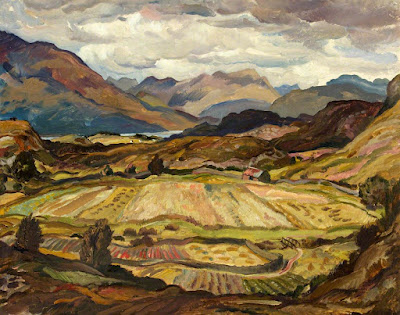

Alexander Docharty (1862-1940), "An Autumn Day" (1917)

I returned from my walk. I have not yet read my poem for the evening. However -- again, one poem leading to another -- I thought of this tonight:

The River

Stir not, whisper not,

Trouble not the giver

Of quiet who gives

This calm-flowing river,

Whose whispering willows,

Whose murmuring reeds

Make silence more still

Than the thought it breeds,

Until thought drops down

From the motionless mind

Like a quiet brown leaf

Without any wind;

It falls on the river

And floats with its flowing,

Unhurrying still

Past caring, past knowing.

Ask not, answer not,

Trouble not the giver

Of quiet who gives

This calm-flowing river.

Patrick MacDonogh (1902-1961), Poems (edited by Derek Mahon) (The Gallery Press 2001), page 86.

Rustling leaves. Sparrows. Autumn into winter. The river.

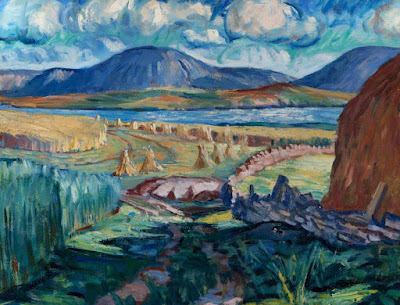

William Samuel Jay (1843-1933)

"At the Fall of Leaf, Arundel Park, Sussex" (1883)