In this part of the world, one must learn to embrace greyness and inclemency. Otherwise, you may find it difficult to venture beyond your doorstep. You learn to adapt. For instance, after living here a certain number of years, one day, without making a conscious decision to do so, you stop using umbrellas. It just happens. Cumbersome things, after all. A hat or a hood (or neither) will do.

But, beyond the minor practicalities, there is this: the World has a way of providing us with compensations, however small and however fleeting. If we fail to remain on the lookout for these compensations, all is lost, whether we abide at the Equator or in farthest Thule.

He who has lived in sunshine all day long,

His happy eyes

From too much light defending,

He cannot duly prize

One gleam of light at the day's ending.

Mary Coleridge, in Theresa Whistler (editor),

The Collected Poems of Mary Coleridge (Rupert Hart-Davis 1954).

The poem is untitled. It was written in 1888.

"One gleam of light" may be all that we get, but it is more than enough. A few days ago, while out for a walk, I saw the first tuft of blossoming crocuses -- pale purple -- next to the sidewalk. The dark green shoots of daffodils have begun to emerge as well. Unexpected compensations. Enough to subsist upon.

"All I have been able to do is to walk and go on walking, remember, glimpse, forget, try again, rediscover, become absorbed. I have not bent down to inspect the ground like an entomologist or a geologist; I've merely passed by, open to impressions. I have seen those things which also pass -- more quickly or, conversely, more slowly than human life. Occasionally, as if our movements had crossed -- like the encounter of two glances that can create a flash of illumination and open up another world -- I've thought I had glimpsed what I should have to call the still centre of the moving world. Too much said? Better to walk on . . ."

Philippe Jaccottet (translated by Mark Treharne),

Landscapes with Absent Figures (

Paysages avec Figures Absentes) (Delos Press/Menard Press 1997), page 4. In the original French text, the passage ends with the ellipses.

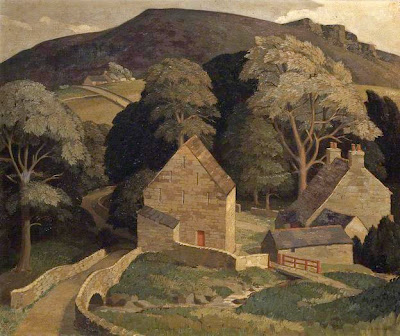

John Aldridge (1905-1983), "February Afternoon"

In this matter of the World's freely-bestowed compensations, we should never forget the miraculous puddle. I have sung the praises of puddles -- those World-reflecting wonders -- in the past, and I will do so again now. At the beginning of last week, on my afternoon walk, I was marveling at how the beauty of bare branches set against a cloud-dappled blue sky becomes deeper, more profound, when seen on the surface of a humble puddle. But that is not the end of it: the beauty takes on yet a different aspect as you begin to walk. All of the intricacy, color, and depth moves along with you, at your feet, as you pass beside the bright water -- an entire upside-down World in motion.

I thought of puddles when I came across these four lines later in the week:

Thou mirror that hast danced through such a world,

So manifold, so fresh, so brave a world,

That hast so much reflected, but, alas,

Retained so little in thy careless depths.

Matthew Arnold, fragment from "Lucretius," in Kenneth Allott (editor),

The Poems of Matthew Arnold (Longmans, Green 1965), page 585.

Allott notes that this fragment echoes a passage in Arnold's "Empedocles on Etna":

Hither and thither spins

The wind-borne, mirroring soul,

A thousand glimpses wins,

And never sees a whole;

Looks once, and drives elsewhere, and leaves its last employ.

Matthew Arnold, "Empedocles on Etna," Act I, Scene II, lines 82-86,

Ibid, page 159.

I'm not quite sure what to make of this image of the soul as a mirror. "Thou mirror that hast danced through such a world,/So manifold, so fresh, so brave a world" is indeed a lovely thought. But, at the risk of oversimplifying (and/or misinterpreting) Arnold's point (which originates in his reading of the philosophical remnants of Empedocles), I wonder if he isn't being a bit too pessimistic about the soul's capabilities. His vision of the soul as a mirror seems far too passive. My limited experience with puddles suggests that some mirrors may "retain" (to use Arnold's word) a great deal of the World upon -- and beneath -- their surfaces.

John Aldridge, "The River Pant near Sculpin's Bridge" (1961)

As the crocuses and the daffodils emerge, the flitting and twittering spirits arrive as well. I recently noticed a single dove disappearing into a bush in the back garden. I hope, as was the case last year, I will be hearing coos outside my window later this spring and through the summer.

Saturday afternoon, walking through the woods, I noticed that the bushes beside the paths have come into leaf. (I hadn't noticed this earlier in the week. I was no doubt inattentive. On the other hand, these things sometimes happen in the space of a day, or overnight.) At the tip of each twig is a single leaf or a small, unfolding spray of leaves. I was entranced by one bush in particular: at the center of each green spray was a circle of tiny white blossoms, a cluster of bright yellow stamens at the heart of each blossom.

The inward frame

Though slowly opening, opens every day

With process not unlike to that which cheers

A pensive Stranger, journeying at his leisure

Through some Helvetian dell, when low-hung mists

Break up, and are beginning to recede;

How pleased he is where thin and thinner grows

The veil, or where it parts at once, to spy

The dark pines thrusting forth their spiky heads;

To watch the spreading lawns with cattle grazed,

Then to be greeted by the scattered huts,

As they shine out; and

see the streams whose murmur

Had soothed his ear while they were hidden: how pleased

To have about him, which way e'er he goes,

Something on every side concealed from view,

In every quarter something visible,

Half-seen or wholly, lost and found again,

Alternate progress and impediment,

And yet a growing prospect in the main.

William Wordsworth, "Home at Grasmere,"

The Recluse, Part I, Book I, lines 472-490, in Ernest de Selincourt and Helen Darbishire (editors),

The Poetical Works of William Wordsworth, Volume 5 (University of Oxford Press 1949).

To combine Arnold and Wordsworth: in "such a world,/So manifold, so fresh, so brave a world," "the inward frame/Though slowly opening, opens every day." Glimpses and glimmers.

John Aldridge, "Roofing a New House"

Last night's sunset over Puget Sound brought to mind these lines: "the red, lurid wreckage of the sunset/Smoulders in smoky fire." (John Masefield, "On Eastnor Knoll.") However, that is too strong a description: it was more delicate than "lurid," more deep orange-pink than primary, burning red. Still, "smoulders in smoky fire" rings true.

But more striking than the sunset was a large oval orange-pink-purple gleam that appeared out in the middle of the Sound after the sun had disappeared beyond the Olympic Mountains. There is surely a scientific explanation for why the pool of light appeared there when it did: something about the sun's declining rays glancing off the clouds,

et cetera. Ah, well, there are always explanations, aren't there? They take the life out of the World.

"Slanting Pillars of Light, like Ladders up to Heaven, their base always a field of vivid green Sunshine."

Samuel Taylor Coleridge, in Kathleen Coburn (editor),

The Notebooks of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Volume 1: 1794-1804 (Pantheon Books 1957), Notebook Entry 1577 (October, 1803).

We should attend to these glimmers and glimpses. Who knows where they will lead us?

"Of all my uncertainties, the least uncertain (the one least removed from the first glimmers of a belief) is the one given to me by poetic experience: the thought that there

is something unknown, something evasive, at the origin of things, at the very centre of our being.

* * * * *

As I reflect on all this I begin to see nonetheless that the poetic experience does give me direction, at least towards a sense of the

high, and this is because I am quite naturally led to see poetry as a glimpse of the Highest and to regard it in a sense (and why not?) as it has been regarded from its very beginnings, as a

mirror of the heavens . . .

* * * * *

(So it would be possible to live without definite hopes, but not without help, with the thought -- so close to certainty -- that if there is a single hope, a single opening for man, it would not be refused to someone who had lived 'beneath this sky.')

(The highest hope would be that the whole sky were really a gaze.)"

Philippe Jaccottet (translated by Mark Treharne),

Landscapes with Absent Figures, pages 157 and 159. The italics and the ellipses are in the original text.

John Aldridge, "Beslyn's Pond, Great Bardfield"