It is enough to drive one into the arms of Giacomo Leopardi for relief: "What is life? The journey of a crippled and sick man walking with a heavy load on his back up steep mountains and through wild, rugged, arduous places, in snow, ice, rain, wind, burning sun, for many days without ever resting night and day to end at a precipice or ditch, in which inevitably he falls." (Giacomo Leopardi, Zibaldone, pages 4162-4163 (January 17, 1826) (edited by Michael Caesar and Franco D'Intino) (Farrar, Straus and Giroux 2013), page 1809.)

Or, alternatively, one can pay a visit to Leopardi's soulmate, the always antic Arthur Schopenhauer: "Awakened to life out of the night of unconsciousness, the will finds itself as an individual in an endless and boundless world, among innumerable individuals, all striving, suffering, and erring; and, as if through a troubled dream, it hurries back to the old unconsciousness." (Arthur Schopenhauer, "On the Vanity and Suffering of Life," in The World as Will and Representation, Volume II (1844) (translated by E. F. J. Payne) (The Falcon's Wing Press 1958), page 573.) Schopenhauer wrote of Leopardi: "[E]verywhere his theme is the mockery and wretchedness of this existence. He presents it on every page of his works, yet in such a multiplicity of forms and applications, with such a wealth of imagery, that he never wearies us, but, on the contrary, has a diverting and stimulating effect." (Ibid, page 588.) Two peas in a pod.

But I'm afraid Leopardi and Schopenhauer simply won't do. As entertaining as they are (their harrowing doom shot through with truth, and so unremittingly dire that one cannot help but smile), I have continued to spend most of my time with Walter de la Mare and the Japanese poets. Calmness and equanimity. A few days ago, I read this:

The Last Chapter

I am living more alone now than I did;

This life tends inward, as the body ages;

And what is left of its strange book to read

Quickens in interest with the last few pages.

Problems abound. Its authorship? A sequel?

Its hero-villain, whose ways so little mend?

The plot? still dark. The style? a shade unequal.

And what of the dénouement? And, the end?

No, no, have done! Lay the thumbed thing aside;

Forget its horrors, folly, incitements, lies;

In silence and in solitude abide,

And con what yet may bless your inward eyes.

Pace, still, for pace with you, companion goes,

Though now, through dulled and inattentive ear,

No more -- as when a child's -- your sick heart knows

His infinite energy and beauty near.

His, too, a World, though viewless save in glimpse;

He, too, a book of imagery bears;

And, as your halting foot beside him limps,

Mark you whose badge and livery he wears.

Walter de la Mare, Memory and Other Poems (Constable 1938).

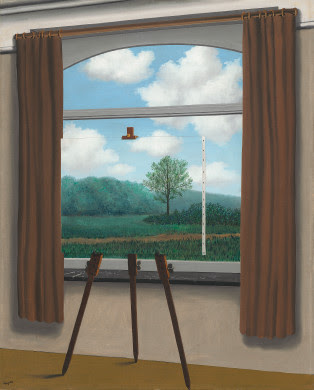

Harry Epworth Allen (1894-1958)

"A Derbyshire Farmstead" (c. 1933-1934)

Who, then, is this "companion" keeping pace with de la Mare? His poetry is full of such secret sharers: shadows, strangers, wayfarers, wraiths, ghosts. I am content to leave the question unanswered, but I have inklings.

Things to Come

The shadow of a fat man in the moonlight

Precedes me on the road down which I go;

And should I turn and run, he would pursue me:

This is the man whom I must get to know.

James Reeves, The Questioning Tiger (Heinemann 1964).

"The man whom I must get to know." This brings to mind the purported death-bed poem of the Emperor Hadrian, which begins: animula vagula blandula. The poem has been translated many times. Here is Matthew Prior's version:

Poor little, pretty, flutt'ring thing,

Must we no longer live together?

And dost thou prune thy trembling wing,

To take thy flight thou know'st not whither?

Thy humorous vein, thy pleasing folly

Lies all neglected, all forgot:

And pensive, wav'ring, melancholy,

Thou dread'st and hop'st thou know'st not what.

Matthew Prior, Poems on Several Occasions (1709).

Finally, I cannot forbear bringing in Marcus Aurelius: "You are a little soul, carrying around a corpse, as Epictetus used to say." Marcus Aurelius (translated by W. A. Oldfather), Meditations, Book IV, Section 41.

These are things we each must puzzle out in our own solitude. Hence, dear readers, please feel free to ignore my meanderings. I am willing to leave de la Mare's "companion" a mystery. Which is what the World is, what our life is, as de la Mare so often reminds us in his poems. Which is what we are to ourselves?

Harry Epworth Allen, "Summer" (1940)

"The Last Chapter" was published when de la Mare was 65 years old. Yet, despite its self-elegiac subject matter and tone, he lived another eighteen years, and never lost his love for the beautiful particulars of the World. In the year prior to his death, he said to a visitor: "My days are getting shorter. But there is more and more magic. More than in all poetry. Everything is increasingly wonderful and beautiful." (Theresa Whistler, Imagination of the Heart: The Life of Walter de la Mare (Duckworth 1993), page 443.) The plea to us to love the World while we can is a constant refrain in his poetry. It appears in what are perhaps his best-known lines: "Look thy last on all things lovely,/Every hour."

He reminds us once more in his final volume of poems, published when he was in his eightieth year:

Now

The longed-for summer goes;

Dwindles away

To its last rose,

Its narrowest day.

No heaven-sweet air but must die;

Softlier float,

Breathe lingeringly

Its final note.

Oh, what dull truths to tell!

Now is the all-sufficing all

Wherein to love the lovely well,

Whate'er befall.

Walter de la Mare, O Lovely England and Other Poems (Faber and Faber 1953).

Perhaps de la Mare sold himself short in the lines from "The Last Chapter" about his "companion": "No more -- as when a child's -- your sick heart knows/His infinite energy and beauty near." The poetry he wrote before and after these lines belies this thought: I find no waning of energy or beauty in de la Mare from beginning to end. Thoughts such as those in "The Last Chapter" inevitably come and go as one ages. But I do not think de la Mare ever lost his passion for the World. He gently but firmly reminds us again and again to love, to pay attention to, and to be grateful for what is before us Now.