The Bells

Shadow and light both strove to be

The eight bell-ringers' company,

As with his gliding rope in hand,

Counting his changes, each did stand;

While rang and trembled every stone,

To music by the bell-mouths blown:

Till the bright clouds that towered on high

Seemed to re-echo cry with cry.

Still swang the clappers to and fro,

When, in the far-spread fields below,

I saw a ploughman with his team

Lift to the bells and fix on them

His distant eyes, as if he would

Drink in the utmost sound he could;

While near him sat his children three,

And in the green grass placidly

Played undistracted on: as if

What music earthly bells might give

Could only faintly stir their dream,

And stillness make more lovely seem.

Soon night hid horses, children, all,

In sleep deep and ambrosial.

Yet, yet, it seemed, from star to star,

Welling now near, now faint and far,

Those echoing bells rang on in dream,

And stillness made even lovelier seem.

Walter de la Mare, The Listeners and Other Poems (Constable 1912).

As is often the case in de la Mare's poetry, the poem is an evocation of Beauty, coupled with a meditation upon how each moment of Beauty we experience can continue to resonate -- and remain -- in our lives in ways we can never anticipate. This coarse description of the poem is the sort of thing I always counsel against. To wit: Explanation and explication are the death of poetry. I should follow my own advice. Best to read the poem, keep silent, and rejoice in the particulars.

For instance, consider the repetition of the "dream"/"seem" rhymes in lines 19 and 20 and in lines 25 and 26, with the accompanying repetition of line 20 ("And stillness make more lovely seem") -- with slight modifications -- in line 26 ("And stillness made even lovelier seem"). And, of course, where would we be without de la Mare's fondness for the word "lovely"? "Look thy last on all things lovely,/Every hour." ("Fare Well.") "Now is the all-sufficing all/Wherein to love the lovely well,/Whate'er befall." ("Now.") The "modernists" of de la Mare's day and the moderns of our own day (with their own fondness for supercilious irony) have no use for a word such as "lovely." No surprise there.

Bertram Priestman (1868-1951), "Suffolk Water Meadows" (1906)

Philippe Jaccottet died on February 24, 2021 at the age of 95. On March 4 of that year, his two final works were published in France: an essay (although "essay" seems too prosaic a word) (La Clarté Notre-Dame) and a collection of poems (Le Dernier Livre de Madrigaux). The two works have been translated into English by John Taylor and have been published together in a single volume. I ordered a copy of the book, and it arrived last Friday.

That evening I started to read La Clarté Notre-Dame. It begins:

"Note dated 19 September 2012: 'This spring, don't forget the little vesper bell of La Clarté Notre-Dame, which sounds incredibly clear in the vast, grey, silent landscape -- truly like a kind of speech, call or reminder, a pure, weightless, fragile, yet crystal-clear tinkling -- in the grey distance of the air.'

"(Indeed, this: I must keep it alive like a bird in the palm of my hand, preserved for a flight that is still possible if one is not too clumsy, or too weary, or if the distrust of words doesn't prevail over it.)"

Philippe Jaccottet (translated by John Taylor), in Philippe Jaccottet, 'La Clarté Notre-Dame' and 'The Last Book of the Madrigals' (Seagull Books 2022), page 5. The italics appear in the original text.

After this two-sentence introduction, Jaccottet continues:

"On a day perhaps at the end of winter (after checking it was 4th of March, thus about a year ago), while walking with friends and barely talking in a vast landscape heading down a gentle slope to a remote valley, under a grey sky, and it's another kind of greyness that predominates in such a season in these otherwise empty fields where no one is working yet, where we're the only ones walking, with no haste and no other goal than getting some fresh air.

* * * * * *

"Up until then, nothing particularly strange, or that might have moved us. At best, perhaps, a kind of prelude to something we didn't know. Until the little vesper bell of La Clarté Notre-Dame Convent, which we still couldn't see at the bottom of the valley, began to ring far below us, at the heart of all this almost-dull greyness. I then said to myself, reacting in a way that was both intense and confusing (and so many times in similar moments I'd been forced to bring together the two epithets), that I'd never heard a tinkling -- prolonged, almost persistent, repeated several times -- as pure in its weightlessness, in its extreme fragility, as genuinely crystalline. . . . Yet which I couldn't listen to as if it were a kind of speech -- emerging from some mouth. . . . A tinkling so crystalline that it seemed, as it appeared, oddly, almost tender. . . . Ah, this was obviously something that resisted grasping, defied language, like so many other seeming messages from afar -- and this frail tinkling lasted, persisted, truly like an appeal, or a reminder . . ."

Ibid, pages 5-7. The italics and ellipses appear in the original text.

Reading the passages above, I am reminded of this: "A thing is beautiful to the extent that it does not let itself be caught." (Philippe Jaccottet (translated by John Taylor), "Blazon in Green and White," in Philippe Jaccottet, And, Nonetheless: Selected Prose and Poetry, 1990-2009 (Chelsea Editions 2011), page 53.)

Bertram Priestman, "The Sun-Veiled Hills of Wharfedale" (1917)

Having the vesper bell of the convent of La Clarté Notre-Dame arrive unexpectedly just a few days after reading "The Bells" was a nice bit of serendipity. I know nothing about how to live, and I possess no wisdom, but age has taught me that, when it comes to Beauty, one thing leads to another. Whether this happens by chance, or by placing oneself in the way of Beauty, or by a combination of both, I don't know. But I do know that, when the stepping stones of Beauty appear, one ought to follow their path.

Thus, the bells of the English countryside and a vesper bell chiming from a valley in France set me to thinking about the sound of bells. Eventually, again by way of Walter de la Mare -- this time through Come Hither, his wonderful anthology of poetry -- this came to mind:

Against Oblivion

Cities drowned in olden time

Keep, they say, a magic chime

Rolling up from far below

When the moon-led waters flow.

So within me, ocean deep,

Lies a sunken world asleep.

Lest its bells forget to ring,

Memory! set the tide a-swing!

Henry Newbolt (1862-1938), in Walter de la Mare (editor), Come Hither: A Collection of Rhymes and Poems for the Young of All Ages (Constable 1923), page 214. In Come Hither, de la Mare gives the poem the title "Cities Drowned." However, when the poem was originally published, Newbolt titled it "Against Oblivion." (Henry Newbolt, Songs of Memory and Hope (John Murray 1909), page 50.) Newbolt and de la Mare were close friends, and Newbolt encouraged de la Mare when he embarked upon his literary career. "Against Oblivion" in fact sounds like something de la Mare himself could have written.

"Against Oblivion" is the penultimate poem in the section of Come Hither titled "Dance, Music and Bells." I proceeded to the poem which follows it:

The Bell-man

From noise of Scare-fires rest ye free,

From Murders -- Benedicite.

From all mischances, that may fright

Your pleasing slumbers in the night:

Mercie secure ye all, and keep

The Goblin from ye, while ye sleep.

Past one aclock, and almost two,

My Masters all, Good day to you!

Robert Herrick, in Walter de la Mare (editor), Come Hither: A Collection of Rhymes and Poems for the Young of All Ages, page 215. "Benedicite" is "an expletive of good omen, used after the mention of some evil word or thing." (Tom Cain and Ruth Connolly (editors), The Complete Poetry of Robert Herrick, Volume II (Oxford University Press 2013), page 611 (quoting the Reverend Charles Percival Phinn).) The Reverend Phinn (who died in 1906) was an indefatigable and thorough annotator of Herrick's poetry. His annotations were never published, but were preserved in the margins of his copy of Herrick's poems. (Ibid, Volume I, page 432.) The annotations have been praised, and relied upon, by modern editors of Herrick's poetry.

Herrick's poem provided another stepping stone, leading once again to Walter de la Mare:

Then

Twenty, forty, sixty, eighty,

A hundred years ago,

All through the night with lantern bright

The Watch trudged to and fro.

And little boys tucked snug abed

Would wake from dreams to hear --

'Two o' the morning by the clock,

And the stars a-shining clear!'

Or, when across the chimney-tops

Screamed shrill a North-East gale,

A faint and shaken voice would shout,

'Three! -- and a storm of hail!'

Walter de la Mare, Peacock Pie: A Book of Rhymes (Constable 1913).

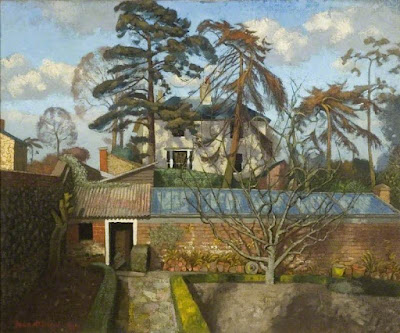

Bertram Priestman, "Wooded Hillside" (1910)

One thing leads to another: from the bells of sunken cities and of night watchmen my thoughts turned, for no apparent reason, to the sound of bells in Japanese poetry. A set of two haiku written by Issa (1763-1828) provided the next stepping stones.

The evening cool;

Not knowing the bell

Is tolling our life away.

Issa (translated by R. H. Blyth), in R. H. Blyth, Haiku, Volume III: Summer-Autumn (Hokuseido Press 1952), page 124.

The evening cool;

Knowing the bell

Is tolling our life away.

Issa (translated by R. H. Blyth), Ibid, page 125.

Of the "four masters" of haiku (the other three being Bashō, Buson, and Shiki), Issa is the most down-to-earth and playful, and is by turns tragic and comic. Commenting on the two haiku, R. H. Blyth writes: "only the enlightened man knows, as part of his hearing the bell, as part of every breath he draws, as part of the coolness, that all is fleeting and evanescent." (Ibid, page 125; the italics appear in the original text.) But who would presume to describe himself or herself as "enlightened"? We know, but we don't know, isn't that the case? It depends on the moment.

I can't imagine that Walter de la Mare would have ever referred to himself as being "enlightened." But he was well aware "that all is fleeting and evanescent." Two days prior to his death, he "wrote to a friend of the midsummer leaf and blossom: 'One looks at it partly with amazed delight and partly with anticipatory regret at its transitoriness'." (Theresa Whistler, Imagination of the Heart: The Life of Walter de la Mare (Duckworth 1993), page 445 and page 459 (footnote 13).) De la Mare's comment in the letter articulates the essence of much of his poetry.

Issa's complementary and provocative haiku were not the stopping point. At a certain stage in your life, you learn to be patient and wait for things to float up. In time, two beloved treasures arrived.

The first treasure:

A quiet bell sounds --

and reveals a village

waiting for the moon.

Sōgi (1421-1502) (translated by Steven Carter), in Steven Carter, The Road to Komatsubara: A Classical Reading of the Renga Hyakuin (Council on East Asian Studies, Harvard University 1987), page 96. The poem is a link in a renga hyakuin (a sequence of one hundred linked verses). Renga consist of alternating three-line and two-line verses (links). The three-line verses/links in renga were the precursors of what eventually became a new poetic form: free-standing haiku.

The second treasure:

To a mountain village

at nightfall on a spring day

I came and saw this:

blossoms scattering on echoes

from the vespers bell.

Nōin (988-1050) (translated by Steven Carter), in Steven Carter, Traditional Japanese Poetry: An Anthology (Stanford University Press 1991), page 134. The poem is a waka.

Both of these poems have appeared here before (the latter on several occasions). They are two of my favorite poems. They speak for themselves.

The sound of bells. Yes, when it comes to Beauty, one thing leads to another.

Bertram Priestman, "The Great Green Hills of Yorkshire" (1913)