Given the situation in which the world now finds itself, I had thought to descant upon the folly and evil of self-appointed emperors and their imaginary, ultimately chimerical empires. I had intended to begin with this:

The Fort of Rathangan

The fort over against the oak-wood,

Once it was Bruidge's, it was Cathal's,

It was Aed's, it was Ailill's,

It was Conaing's, it was Cuilíne's,

And it was Maeldúin's:

The fort remains after each in his turn --

And the kings asleep in the ground.

Anonymous (translated by Kuno Meyer), in Kuno Meyer (editor), Selections from Ancient Irish Poetry (Constable 1913). I first discovered the poem in Walter de la Mare's anthology Come Hither: A Collection of Rhymes and Poems for the Young of All Ages (Constable 1923).

I planned to eventually arrive at this:

In Yüeh Viewing the Past

Kou-chien, king of Yüeh, came back from the broken land of Wu;

his brave men returned to their homes, all in robes of brocade.

Ladies in waiting like flowers filled his spring palace

where now only the partridges fly.

Li Po (701-762) (translated by Burton Watson), in Burton Watson (editor), The Columbia Book of Chinese Poetry: From Early Times to the Thirteenth Century (Columbia University Press 1984).

But I soon realized, dear readers, that I would only be telling you something you already know. Moreover, of what value is historical "perspective" (or the "perspective" of immutable human nature) when singular and irreplaceable lives are being lost, or forever damaged, at this moment? I no longer had any heart for the project. "Perspective" is an inappropriate indulgence for someone who is out of harm's way, living in a place that is not at war.

James McIntosh Patrick (1907-1998), "A Castle in Scotland"

Around the same time, for reasons unknown, I remembered this:

Animula

No one knows, no one cares --

An old soul

In a narrow cottage,

A parlour,

A kitchen,

And upstairs

A narrow bedroom,

A narrow bed --

A particle of immemorial life.

James Reeves, Poems and Paraphrases (Heinemann 1972). "Animula" is usually translated into English as "little soul."

Reeves' poem prompted me to return to a poem purportedly written by the Emperor Hadrian (ah, an emperor) on his deathbed. The poem begins: "animula vagula blandula." It has been translated into English dozens of times over the centuries. My favorite version is that of Henry Vaughan:

My soul, my pleasant soul and witty,

The guest and consort of my body,

Into what place now all alone

Naked and sad wilt thou be gone?

No mirth, no wit, as heretofore,

Nor jests wilt thou afford me more.

Henry Vaughan, "Man in Darkness, or, A Discourse of Death," in The Mount of Olives: or, Solitary Devotions (1652), in Donald Dickson, Alan Rudrum, and Robert Wilcher (editors), The Works of Henry Vaughan, Volume I: Introduction and Texts, 1646-1652 (Oxford University Press 2018), page 318.

As a preface to his translation of the poem, Vaughan writes:

"You may believe, he was royally accommodated, and wanted nothing which this world could afford; but how far he was from receiving any comfort in his death from that pompous and fruitless abundance, you shall learn from his own mouth, consider (I pray) what he speaks, for they are the words of a dying man, and spoken by him to his departing soul."

Ibid, page 318.

Finally, Hadrian and Vaughan led me to T. S. Eliot's "Animula," and, in particular, these lines:

'Issues from the hand of God, the simple soul'

To a flat world of changing lights and noise,

To light, dark, dry or damp, chilly or warm;

Moving between the legs of tables and of chairs,

Rising or falling, grasping at kisses and toys,

Advancing boldly, sudden to take alarm,

Retreating to the corner of arm and knee,

Eager to be reassured, taking pleasure

In the fragrant brilliance of the Christmas tree,

Pleasure in the wind, the sunlight and the sea.

* * * * *

Issues from the hand of time the simple soul

Irresolute and selfish, misshapen, lame,

Unable to fare forward or retreat,

Fearing the warm reality, the offered good,

Denying the importunity of the blood,

Shadow of its own shadows, spectre in its own gloom,

Leaving disordered papers in a dusty room;

Living first in the silence after the viaticum.

T. S. Eliot, "Animula," lines 1-10 and 24-31, in Collected Poems 1909-1935 (Harcourt, Brace and Company 1936).

James McIntosh Patrick, "Springtime in Eskdale" (1935)

There is yet another way of considering this matter: "You are a little soul, carrying around a corpse, as Epictetus used to say." Marcus Aurelius, Meditations, Book IV, Section 41 (translated by W. A. Oldfather).

Marcus Aurelius' quotation from Epictetus may be read in light of the section of the Meditations which immediately precedes it, and which is quite wonderful:

"Cease not to think of the Universe as one living Being, possessed of a single Substance and a single Soul; and how all things trace back to its single sentience; and how it does all things by a single impulse; and how all existing things are joint causes of all things that come into existence; and how intertwined in the fabric is the thread and how closely woven the web."

Marcus Aurelius, Meditations, Book IV, Section 40 (translated by C. R. Haines).

Empires. Animula. And yesterday afternoon I walked through Spring, which persists in being here, despite everything. "How intertwined in the fabric is the thread and how closely woven the web."

A man of the Way comes rapping at my brushwood gate,

wants to discuss the essentials of Zen experience.

Don't take it wrong if this mountain monk's too lazy to open his

mouth:

late spring warblers singing their heart out, a village of drifting

petals.

Jakushitsu Genkō (1290-1367) (translated by Burton Watson), in Burton Watson, "Poems by Jakushitsu Genkō," The Rainbow World: Japan in Essays and Translations (Broken Moon Press 1990), page 127.

What are we to do? "It's a sad and beautiful world." (Mark Linkous (performing as Sparklehorse), "Sad and Beautiful World.")

To a mountain village

at nightfall on a spring day

I came and saw this:

blossoms scattering on echoes

from the vespers bell.

Nōin (988-1050) (translated by Steven Carter), in Steven Carter (editor), Traditional Japanese Poetry: An Anthology (Stanford University Press 1991), page 134.

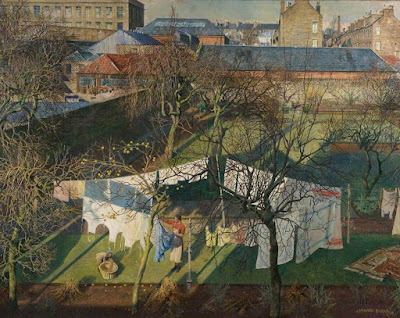

James McIntosh Patrick, "A City Garden" (1940)